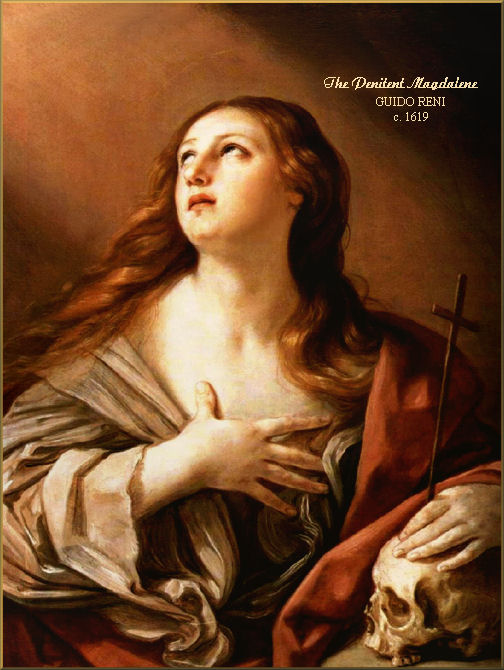

Excerpts from Ven. Archbishop Sheen's LIFT UP YOUR HEART, 1950  Making Up For the Past In an earlier chapter the necessity of living in the Now was stressed: the moment and its opportunities were shown to be our only proper subject for concern. But this assumed that the past had, indeed, been rectified, robbed of its right to haunt our minds by penance done for its offenses. Until this is accomplished, the problem of what to do about our past misdeeds is a serious one, since we do not, like animals, live in the present. The past stays with us in our habits, in our consciousness of remembered guilt, in our proclivity to repeat the same sin. Our past experiences are in our blood, our brains, and even in the very expression that we wear. The future Judgment is also with us; it haunts us, causing our anxieties and fears, our dreads and preoccupations, giving us insecurity and uncertainty. A cow or a horse lives for the present moment, without remorse or anxiety; but man not only drags his past with him, but he is also burdened with worries about his eternal future. [Emphasis in bold added here and infra.] Because the past is with him in the form of remorse or guilt, because the future is with him in his anxiety, it follows that the only way man can escape either burden is by reparation -making up for the wrong done in the past - and by a firm resolution to avoid such sin in the future. Disposing of the past is the first step to take, and in taking it, the important distinction between forgiveness and reparation for sin should be remembered. Some who have done wrong mistakenly think that they should only forget it, now that it is past and "done with"; others believe, falsely, that once a wrong deed has been forgiven, nothing further need be done. But both of these attitudes are incomplete, lacking in love. As soon as a soul comes in contact with Our Lord and realizes he has wounded such Love, his first response after being forgiven is apt to be that of Zachary: "I will repay all." Our Lord, in instituting the Sacrament of Penance, made it clear that there is a difference between forgiveness and the undoing of the past. That is why Confession is followed by Absolution, or forgiveness, and why, when Absolution has been given, the confessor says: "For your penance. ..." Then he tells the penitent what prayers to say or which good actions to perform to make atone- ment for his sins. The high reasonableness of this is apparent if we translate the offense against God into purely human terms. Suppose that I have stolen your watch. When my conscience finally pricks me, I admit it all to you and say: "Will you forgive me?" No doubt you will, but I am sure that you will also say: "Give me back the watch." Returning the watch is the best proof of the sincerity of my regret. Even children know there must be a restoration of the balance, or equilibrium, disturbed by sin: a boy who breaks a window playing ball often volunteers, "I'll pay for it." Forgiveness alone does not wipe out the offense. It is as if a man, after every sin, were told to drive a nail into a board and, every time he was forgiven, a nail were pulled out. He would soon discover that the board was full of holes which had not been there in the beginning. Similarly, we cannot go back to the innocence that our sins have destroyed. When we turned our backs upon God by sinning against Him, we burned our bridges behind us; now they have to be rebuilt with patient labor. A businessman who has contracted heavy debts will find his credit cut off; until he has begun to settle the old obligations, he cannot carry on his business. Our old sins must be paid for before we can continue with the business of living. Reparation is the act of paying for our sins. When that is done, God's pardon is available to us. His pardon means a restoration of the relationship of love - just as, if we offend a friend, we do not consider that we are forgiven until the friend loves us again. God's mercy is always present. His forgiveness is forever ready, but it does not become operative until we show Him that we really value it. The father of the prodigal son had forgiveness always waiting in his heart; but the prodigal son could not avail himself of it until he had such a change of disposition that he asked to be forgiven and offered to do penance as a servant in his father's house. So long as we continue our attachment to evil, forgiveness is impossible; it is as simple as the law which says that living in the deep recesses of a cave makes sunlight unavailable to us. Pardon is not automatic - to receive it, we have to make ourselves pardonable. The proof of our sorrow over having offended is our readiness to root out the vice that caused the offense. The man who holds a violent grudge against his neighbor and who confesses it in the Sacrament of Penance cannot be forgiven unless he forgives his enemy. "If you do not forgive, your Father Who is in Heaven will not forgive your transgressions either." (Mark 11:26.) The humiliation involved in confessing sins does much to make us avoid them in the future. But we must offer more than our humiliation: satisfaction is also required of us. If it is not given in this life, it will have to be made up in the next. "Saying penances" - "satisfying" for sins - would be a pitifully inadequate compensation for the damage we have done if it were not that Christ Himself offers satisfaction through our petty penances, giving them a value far beyond their own. If we look only at our part in satisfying for our sins, we should expect penances to be very arduous, as they were in the early Church; if we stress the Divine contribution to their efficacy, then we can understand why they are as light as they are today. But in neither case is it possible to fix any realistic scale of payment, for the satisfaction comes from Our Lord. "So, on the cross, His Own body took the weight of our sins; we were to become dead to our sins, and live for holiness; it was His wounds that healed you." (1 Pet. 2:24.) Associated with the Christian's amendment for the past is his resolution for the future. This must be more than a wish to avoid evil - it must be a will to do so. For there is a vast difference between velleity, or the mere desire to be better, and volition, or a firm determination to be better. Pilate wished to save Our Lord, but he did not will to save Him. Remorse for the past involves a wish to avoid the same sin, but in the vague hope that this can be accomplished without giving up anything; repentance uses no "ifs" and "buts" but sets to work on the unpleasant task of rooting up the evil. We cannot be like the dying woman who, when she was asked to renounce the Devil, said: "But I do not like to make enemies unnecessarily!"  The knowledge that a sin has been committed often in the past does not exclude a firm purpose against sinning the same way in the future, provided that it is accompanied by a strong trust in the Mercy of God, Who will not suffer us to be tempted beyond our strength. Those who have never gone to Confession or tried to amend their lives must not be too hard on the souls who are trying; people who give in to every temptation have no idea how hard it is for us to resist the sins which have been committed before. If anyone wants to find out how bad he is, let him try to be good. One tests the current of a river, not by flowing with it, but by fighting against it. Bad people know nothing about goodness, because they are always floating downstream with the current of badness. They should not be supercilious about those defeated swimmers whom Our Lord forgives "seventy times seven" or about His Mystical Body, which prolongs that Mercy to all sinners who really care and try. Moreover, anyone who refuses to avoid the proximate occasions of a grievous sin into which he has repeatedly fallen is considered as wanting in resolution to avoid that sin and is denied absolution in the Sacrament. Unrepented and unforgiven sins are the commonest causes of fear and anxiety. Many neurotics, who profess no religion, do not realize that their troubles are due to a hidden guilt. To deny the existence of our past sin is as serious to a soul as the denial of an existing cancer is serious to the body. An uneasy conscience is always anxious as to the future - just as an embezzler who is presently stealing from a bank lives in dread of being caught. The mere denial of the concept of sin does not relieve our guilt: the conscience of man will not be bribed so easily, nor fobbed off with a shallow denial of the moral law which is engraved in all our natures. The only real escape from the anxiety of guilt is to restore oneself to union with Divine Righteousness through penitence. The past is blotted out by His forgiveness, and worries over a future reckoning disappear. Hence Sacred Scripture gives us this sound psychiatric advice: "Love drives out fear, when it is perfect love." (I John 4:18.) In the case of Mary Magdalene, Christ's fullness of love wiped out her sin, her fear, and even the punishment due to sin. "And so, I tell thee, if great sins have been forgiven her, she has also greatly loved." (Luke 7:47.) Repentance for sin is inseparable from love. Our hatred of sin is a measure of the deepness of love. God would not be good unless He hated evil, nor can any of us claim to value the Divine Love unless we avoid all that would wound that Love. To love a fellow creature we must first know him - but in the case of God the reverse is true, and to know Him we must love Him first. If we love, we shall want to separate ourselves from anything that might be harmful to that love. For love always seeks to be with the one loved; love always seeks to please the one loved; love is ready to suffer for the one loved; love hates what hurts the one loved; love never feels that it can do enough for the one loved. The laws of all love apply here, too, and Our Lord in His teaching told us how we might express ours for Him in many ways. For instance, we are to repay evil with good. "If a man strikes thee on thy right cheek, turn the other cheek also toward him; if he is ready to go to law with thee over thy coat, let him have it and thy cloak with it." (Matt. 5:39.) He also wishes us to overcome our self-will by charity to our neighbor. "If he compels thee to attend him on a mile's journey, go two miles with him of thy own accord." (Matt. 5:41.) We are to love our enemies. "Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, pray for those who persecute and insult you, that so you may be true sons of your Father in Heaven." (Matt. 5:44.) And all this is to be done with joy. "Again when you fast, do not shew it by gloomy looks, as the hypocrites do. But do thou, at the times of fasting, anoint thy head and wash thy face, so that thy fast may not be known to men, but to thy Father Who dwells in secret; and then thy Father, Who sees what is done in secret, will reward thee." (Matt. 6:16-18.) The effort to apply these laws of love eventually brings us to a higher kind of repentance, in which some souls do penance, not only for their own sins, but for the sins of others. Deeply loving souls are conscious of their unity with all mankind and wish to satisfy for the guilt of others as their own. Their mission in life is to make pardon available to those too blind to ask for it them. selves. In the moral order, this is as if the comparatively healthy - seeing the injuries from which others suffer - should offer to bind up their wounds. If love, in the face of physical misery, tries to relieve the pain of others, then love, in the face of sin, is even more concerned to cure the guilt of others. This .is the work Our Lord perfoRMed in the Garden of Gethsemane when He took the iniquities of all upon His Soul, as if He had wrought them - into His blood, as if He had experienced them. It was the horror of our sins which caused Him to burst into a sweat, in which His blood crimsoned the olive roots of the Garden. Our Lord's first follower and emulator in this high mission of Redemption was the Blessed Mother, who claimed no immunity, no noblesse oblige from the vocation of suffering from sin. Although she had no personal guilt requiring satisfaction, she allowed her heart to be pierced by the swords of evil done by other men and women. She too, in Her more limited way than His, would share the world's guilt as Her own. The same high mission is continued today in the contemplative orders of the Church: the Trappists, Carmelites, Poor Clares, and dozens of other gifted souls renounce the world, not because they want to save only their own souls, but because they want to save the souls of others. The cloistered religious are like spiritual blood banks, storing up the red energy of salvation for those anemic souls who sin and do not atone. It is possible that these souls, praying and fasting in secret, are alone holding back the arm of God's Wrath from a rebellious and a blasphemous age. As ten just men could have saved Sodom and Gomorrah, so a scattered few of these consecrated victims may save a nation or the world. Their merits overflow to others who have made no contribution to goodness, as the benefits of electricity come to many of us who have never put a screw into a dynamo. The communicability of merits in the Communion of Saints is one of the most beautiful and consoling truths taught by the Church. Love between its members does not operate only on the horizontal plane - between one person and another - but resembles a triangle; a sacrificial prayer breathed on earth is lifted up to Our High Priest, Christ in Heaven; He transubstantiates it with His merits and sends it down to earth again to enrich the sinful soul in need. As it is possible to graft skin from one part of the body to another to heal a burn, so it is possible in the Mystical Body to graft a prayer; as it is possible to transfuse blood from one healthy person to another to cure him of his weakened condition, so it is possible to transfuse sacrifice. Because sacrificial souls love God and long to undo what ever has offended Him, they see other people's sins as their own, as works of evil they are called to set aright by sacrifice and prayer. The Saint believes that to know of another's sin is to be obliged to do penance for it - God, he feels, has made him clear-sighted about another's sin only in order that he may undo the damage. He does not scold the sinner for not doing the work himself. Tolerance says: "He is as good as I am." Charity says: "He may be far better than I." By this the Saint means that if the other man knew God's love as he knows it, the present sinner might love Him much more fervently than the Saint. The fully Christian soul not only forgives others; it suffers for others, takes on others' sins as its sins. The best men and women never consider that they are good; they feel constantly in need of Divine Mercy for their own failures to love perfectly; to merit it, their hearts overflow in mercy and kindness to others. The sinful conscience is cruel and cynical; the repentant conscience is kind and filled with Charity.  Reparation, like self-discipline, depends on love of God. It does no good to tell people to stop doing certain things, unless they can be given something else to do that they will care for more. An alcoholic will not be persuaded to give up the liquor he loves unless he is made to love something else. For evil can never be thrown out; it must be crowded out. When finally a Perfect Love is found, there is less adhesion to other things; when a soul responds to the limit of its capacities to that love, there often follows a longing to take on others' burdens as one's own, that they may not miss the glory of an intimacy with Love, for which they were intended. St. Catherine of Siena once said: "Lord, how could I be content if anyone of those who have been created in Thy image and likeness, even as I, should perish and be taken out of Thy hands. I would not in any wise that even one should be lost of my brethren, who are bound to me by nature and by grace. Better were it for me that all should be saved, and I alone (saving ever Thy Charity) should sustain the pains of Hell, than that I should be in Paradise and all they perish, damned; for greater honor and glory of Thy Name would it be." At another time her prayer was: "Lord, give me all the pains and all the infirmities that there are in the world to bear in my body; I am faint to offer Thee my body in sacrifice and to bear all for the world's sins, that Thou mayest spare it and change its life to another." Though such an ideal is transcendent to most of us, it is still well for the world to have some souls dedicated to ideals which the mass of men will never practice. The illiterate in a village will point with pride to the one man who can read and write; through him, they derive their education vicariously. The Saints fulfill such a spiritual role in humanity - through them, some satisfaction is made vicariously for the failings of us all. As soldiers offer their lives that the non-combatants can preserve political freedom in time, so these soldiers of Christ sacrifice their lives that others may enjoy their spiritual freedom in eternity. DOWNLOAD THE ROSARY MADONNA IMAGE PLAIN  E-MAIL E-MAIL DIRECTORIES--------------------------HOME www.catholictradition.org/Classics/sheen-excerpt7.htm |