|

THE

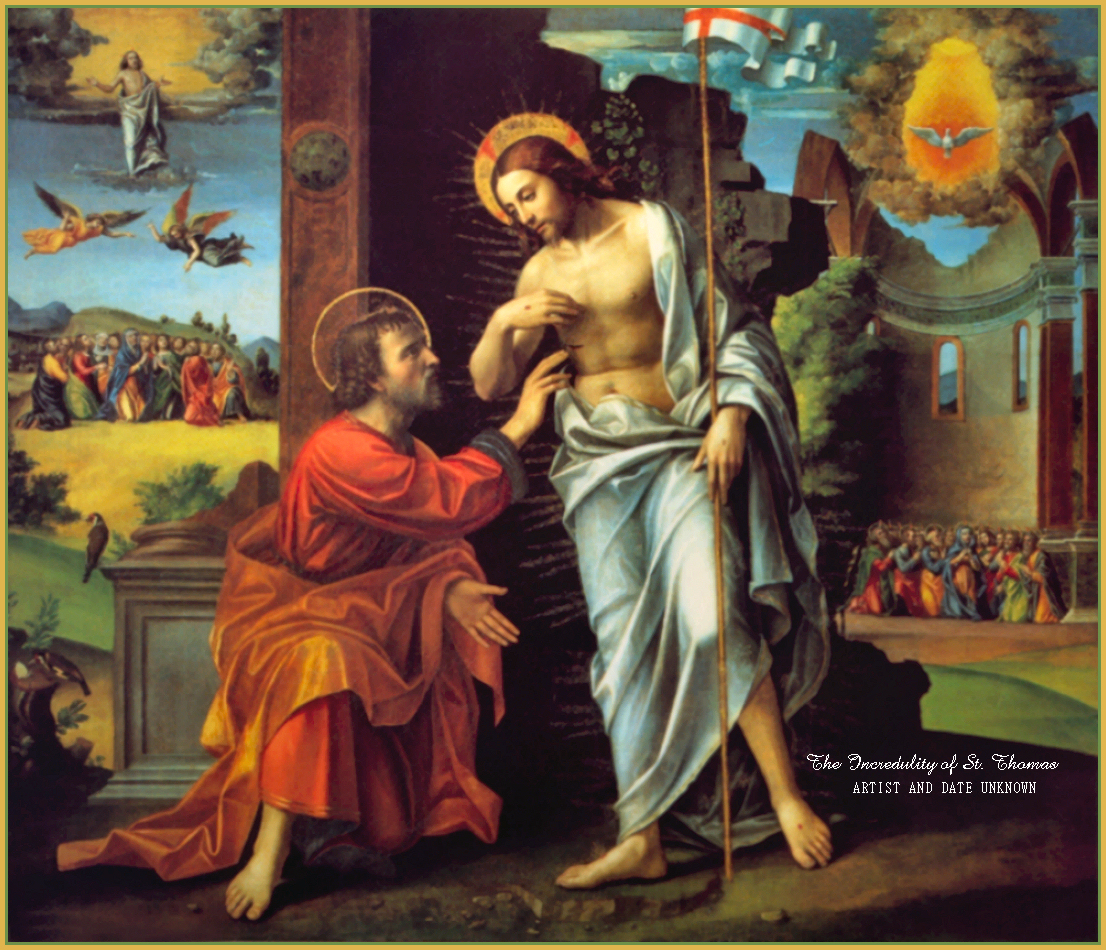

OCTAVE OF THE PASCH Taken from THE LITURGICAL YEAR OUR neophytes closed the Octave of the Resurrection yesterday. They were before us in receiving the admirable mystery; their solemnity would finish earlier than ours. This, then, is the eighth day for us who kept the Pasch on the Sunday, and did not anticipate it on the vigil. It reminds us of all the glory and joy of that feast of feasts, which united the whole of Christendom in one common feeling of triumph. It is the day of light, which takes the place of the Jewish Sabbath. Henceforth, the first day of the week is to be kept holy. Twice has the Son of God honored it with the manifestation of His almighty power. The Pasch, therefore, is always to be celebrated on the Sunday; and thus every Sunday becomes a sort of Paschal feast, as we have already explained in the Mystery of Easter. Our risen Jesus gave an additional proof that He wished the Sunday to be, henceforth, the privileged day. He reserved the second visit He intended to pay to all His disciples for this the eighth day since His Resurrection. During the previous days, He has left Thomas a prey to doubt; but today He shows himself to this Apostle, as well as to the others, and obliges him, by irresistible evidence, to lay aside his incredulity. Thus does our Savior again honor the Sunday. The Holy Ghost will come down from Heaven upon this same day of the week, making it the commencement of the Christian Church: Pentecost will complete the glory of this favored day. Jesus' apparition to the eleven, and the victory He gains over the incredulous Thomas-----these are the special subjects the Church brings before us today. By this apparition, which is the seventh since His Resurrection, our Savior wins the perfect faith of His disciples. It is impossible not to recognize God in the patience, the majesty, and the charity of Him who shows Himself to them. Here, again, our human thoughts are disconcerted; we should have thought this delay excessive; it would have seemed to us that our Lord ought to have at once either removed the sinful doubt from Thomas's mind, or punished him for his disbelief. But no: Jesus is infinite wisdom, and infinite goodness. In His wisdom, He makes this tardy acknowledgment of Thomas become a new argument of the truth of the Resurrection; in His goodness, He brings the heart of the incredulous disciple to repentance, humility, and love; yea, to a fervent and solemn retraction of all his disbelief. We will not here attempt to describe this admirable scene, which holy Church is about to bring before us. We will select, for our today's instruction, the important lesson given by Jesus to His disciple, and through him to us all. It is the leading instruction of the Sunday, the Octave of the Pasch, and it behooves us not to pass it by, for, more than any other, it tells us the leading characteristic of a Christian, shows us the cause of our being so listless in God's service, and points out to us the remedy for our spiritual ailments. Jesus says to Thomas: 'Because thou hast seen Me, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and have believed!' Such is the great truth, spoken by the lips of the God-Man: it is a most important counsel, given, not only to Thomas, but to all who would serve God and secure their salvation. What is it that Jesus asks of His disciple? Has he not heard him make profession that now, at last, he firmly believes? After all, was there any great fault in Thomas's insisting on having experimental evidence before believing in so extraordinary a miracle as the Resurrection? Was he obliged to trust to the testimony of Peter and the others, under penalty of offending his Divine Master? Did he not evince his prudence, by withholding his assent until he had additional proofs of the truth of what his brethren told him? Yes, Thomas was a circumspect and prudent man, and one that was slow to believe what he had heard; he was worthy to be taken as a model by those Christians who reason and sit in judgment upon matters of faith. And yet, listen to the reproach made him by Jesus. It is merciful, and withal so severe! Jesus has so far condescended to the weakness of his disciple as to accept the condition on which alone he declares that he will believe: now that the disciple stands trembling before his risen Lord, and exclaims, in the earnestness of faith, 'My Lord and my God!' oh! see how Jesus chides him! This stubbornness, this incredulity, deserves a punishment: the punishment is, to have these words said to him: 'Thomas! thou hast believed, because thou hast seen!' Then was Thomas obliged to believe before having seen? Yes, undoubtedly. Not only Thomas, but all the Apostles were in duty bound to believe the Resurrection of Jesus even before He showed Himself to them. Had they not lived three years with Him? Had they not seen Him prove Himself to be the Messias and the Son of God by the most undeniable miracles? Had He not foretold them that He would rise again on the third day? As to the humiliations and cruelties of His Passion, had He not told them, a short time previous to it, that He was to be seized by the Jews in Jerusalem, and be delivered to the Gentiles? that He was to be scourged, spit upon, and put to death? [St. Luke xviii 32, 33] After all this, they ought to have believed in His triumphant Resurrection, the very first moment they heard of His Body having disappeared. As soon as John had entered the sepulcher, and seen the winding-sheet, he at once ceased to doubt; he believed. But it is seldom that man is so honest as this; he hesitates, and God must make still further advances, if He would have us give our faith! Jesus condescended even to this: He made further advances. He showed Himself to Magdalen and her companions, who were not incredulous, but only carried away by natural feeling, though the feeling was one of love for their Master. When the Apostles heard their account of what had happened, they treated them as women whose imagination had got the better of their judgment. Jesus had to come in person: He showed Himself to these obstinate men, whose pride made them forget all that He had said and done, sufficient indeed to make them believe in His Resurrection. Yes, it was pride; for faith has no other obstacle than this. If man were humble, he would have faith enough to move mountains. To return to our Apostle. Thomas had heard Magdalen, and he despised her testimony; he had heard Peter, and he objected to his authority; he had heard the rest of his fellow-Apostles and the two disciples of Emmaus, and no, he would not give up his own opinion. How many there are among us who are like him in this! We never think of doubting what is told us by a truthful and disinterested witness, unless the subject touch upon the supernatural; and then we have a hundred difficulties. It is one of the sad consequences left in us by Original Sin. Like Thomas, we would see the thing ourselves: and that alone is enough to keep us from the fulness of the truth. We comfort ourselves with the reflection that, after all, we are disciples of Christ; as did Thomas, who kept in union with his brother-Apostles, only he shared not their happiness. He saw their happiness, but he considered it to be a weakness of mind, and was glad that he was free from it! How like this is to our modern rationalistic Catholic! He believes, but it is because his reason almost forces him to believe; he believes with his mind, rather than from his heart. His faith is a scientific deduction, and not a generous longing after God and supernatural truth. Hence how cold and powerless is this faith! how cramped and ashamed! how afraid of believing too much! Unlike the generous unstinted faith of the Saints, it is satisfied with fragments of truth, with what the Scripture terms diminished truths. [Ps. xi 2] It seems ashamed of itself. It speaks in a whisper, lest it should be criticized; and when it does venture to make itself heard, it adopts a phraseology which may take off the sound of the Divine. As to those miracles which it wishes had never taken place, and which it would have advised God not to work, they are a forbidden subject. The very mention of a miracle, particularly if it have happened in our own times, puts it into a state of nervousness. The lives of the Saints, their heroic virtues, their sublime sacrifices-----it has a repugnance to the whole thing! It talks gravely about those who are not of the true religion being unjustly dealt with by the Church in Catholic countries; it asserts that the same liberty ought to be granted to error as to truth; it has very serious doubts whether the world has been a great loser by the secularization of society. Now it was for the instruction of persons of this class that our Lord spoke those words to Thomas: 'Blessed are they who have not seen, and have believed.' Thomas sinned in not having the readiness of mind to believe. Like him, we also are in danger of sinning, unless our faith have a certain expansiveness, which makes us see everything with the eye of faith, and gives our faith that progress which God recompenses with a superabundance of light and joy. Yes, having once become members of the Church, it is our duty to look upon all things from a supernatural point of view. There is no danger of going too far, for we have the teachings of an infallible authority to guide us. 'The just man liveth by faith.' [Rom. i. 17] Faith is his daily bread. His mere natural life becomes transformed for good and all, if only he be faithful to his Baptism. Could we suppose that the Church, after all her instructions to her neophytes, and after all those sacred rites of their Baptism which are so expressive of the supernatural life, would be satisfied to see them straightway adopt that dangerous system which drives faith into a nook of the heart and understanding and conduct, leaving all the rest to natural principles or instinct? No, it could not be so. Let us therefore imitate St. Thomas in his confession, and acknowledge that hitherto our faith has not been perfect. Let us go to our Jesus, and say to Him: 'Thou art my Lord and my God! But alas! I have many times thought and acted as though thou wert my Lord and my God in some things, and not in others. Henceforth I will believe without seeing; for I would be of the number of those whom Thou callest blessed!' This Sunday, commonly called with us Low Sunday, has two names

assigned

to it in the Liturgy: Quasimodo, from the first word of the

Introit;

and Sunday in albis [or, more explicitly, in albis depositis],

because on this day the neophytes assisted at the Church services

attired

in their ordinary dress. In the Middle Ages it was called Close-Pasch,

no doubt in allusion to its being the last day of the Easter Octave.

Such

is the solemnity of this Sunday that not only is it of Greater Double

rite,

but no feast, however great, can ever be kept upon it.  E-MAIL E-MAIL HOME----------CHRIST THE KING-----------GALLERIES www.catholictradition.org/Easter/easter5.htm |