CHAPTER I

++++++++The Martyrdom of Mary++++++++

|

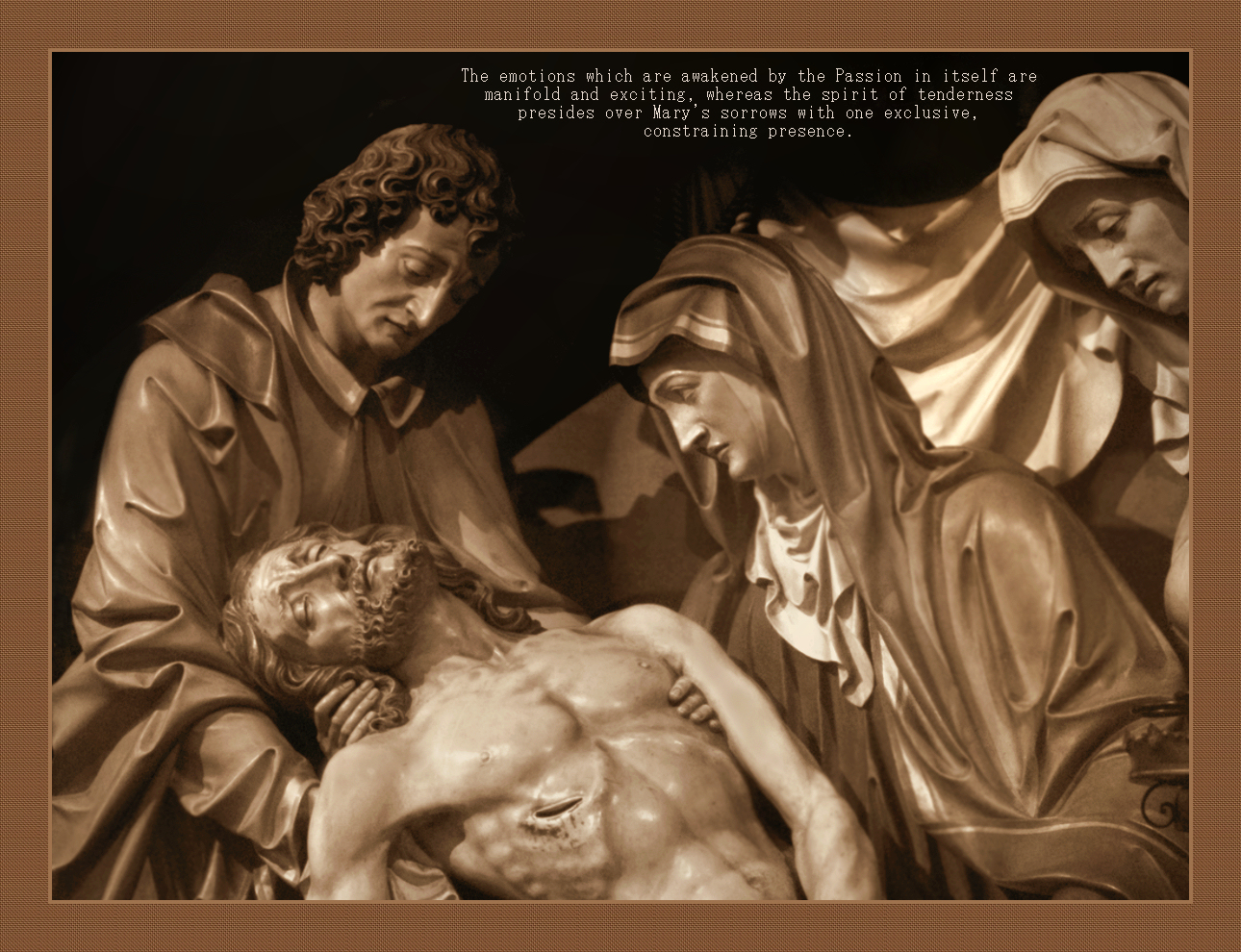

SECTION VII THE SPIRIT OF DEVOTION TO OUR LADY'S DOLORS Before concluding this introductory chapter, however, it seems necessary to say something on the spirit of this beautiful and popular devotion. It produces in our minds an extreme tenderness toward our blessed Lord, united with the profoundest reverence. Jesus demands from us our worship of God. He claims our undoubting faith in His goodness and in the abundance of His redeeming grace. He expects from us a rational conviction that our only trust is in Him, and that we should consequently discharge our duties to Him and obey His Commandments as our necessary and reasonable service. But He wants far more than this. He has something much nearer His heart. He desires our tenderness. He wishes to see us with our hearts always in our hands for Him. He would fain win us to Himself, and unite us with Himself in the bonds of the most familiar and intimate affection. He would have us identify our interests with His, and concentrate our sympathies in Him. The thought of Him should fill our eyes with tears, and kindle our hearts with love. His name should be the sweetest music that we know; His words the laws of all our life. He wishes us, as it were, to forget the precise amount of our actual obligations to Him. Indeed, what is the use of remembering them when we know that it is beyond our power to fulfill them? He would have us deal with Him promptly, generously, abundantly, with the instincts of love, and not as if the life of faith were a spirit of commerce, the balance of justice, the duty of gratitude, or the wise calculations of an intelligent self-interest. We should cling to Him as a child clings to its mother. We should hang about Him as a friend whose absence we cannot bear. We should keep Him fondly in our thoughts, as men sometimes do with a sweet grief, which has become to them the soft and restful light of their whole lives. Now, the way in which our Lady's dolors keep His Passion continually before us has a special virtue to produce this tenderness in us. We love Him, who is infinitely to be loved in all ways, in a peculiar manner when He is reflected in His Mother's heart; and although it is absolutely necessary for us perpetually to contemplate His Passion in all the nakedness of its harrowing circumstances and revolting shame, for else we shall never have a true idea of the sinfulness of sin, yet there is something in the Passion, seen through Mary, which makes us forget ourselves, and tranquilly engrosses us in the most melting tenderness and endearing sympathy toward our Blessed Lord. The emotions which are awakened by the Passion in itself are manifold and exciting, whereas the spirit of tenderness presides over Mary's sorrows with one exclusive, constraining presence. But out of this tenderness comes also a great hatred of sin. If God were to let us choose which of the great and extraordinary gifts that He has given to His Saints should be conferred upon ourselves, we could not do better than ask for that piercing and overwhelming hatred of sin which some have had. It is a gift which lies at the root of all perfection, and is the supernatural vigor of all perseverance. It is at once the safest and the most operative of all singular graces. Devotion to our Lady's dolors is a great help both to acquiring the hatred of sin as a habit, and to meriting it as a grace. The desolation wrought by sin in the heart of the sinless Mother, and the reflection that her sorrows were not, like those of Jesus, the redemption of the world, fill us with horror, with pity, with indignation, with self-reproach. There is nothing to distract us from this thought, as there is in the sacrifice of our Lord, who was thus accomplishing His own great work, satisfying the justice of His Father, earning the exaltation of His Sacred Humanity, and becoming the Father Himself of a countless multitude of the elect. The Mother's heart bleeds, simply because she is His Mother; and it is our sins which are making it bleed so cruelly. We are ourselves part of the shadow of that eclipse which is passing so darkly over her spotless life. We can never help thinking of sin, so long as we see those seven swords, springing, like a dreadful sheaf, from the very inmost sanctuary of her broken heart. Yet there is something also in the dolors, and even in this abhorrence of sin, to make us forget ourselves, without at all periling our safe humility. We rise up from the contemplation of them with a yearning for the conversion of sinners. As if because they were the travail of the Queen of the Apostles, they fill our minds full of apostolic instincts. Whether this is a hidden grace which they communicate, or whether it follows naturally from the subject of meditation, it is certain that this is a favorite devotion with all missionary souls. The fearfulness of losing Jesus, the unbearable anguish of ever so short a separation from Him, the darkness and the dreariness which comes where He is not, these are notable figures in each of the seven processions of those mysterious woes. And how far from Jesus are sinners, misbelievers, heathen! How far out of sight of Calvary have they wandered! How many in number, and in so many ways how dear, are the wanderers! How unfathomable a misery is sin! And to us what a misery those merry voices and bright faces that care not for the misery, but go singing on their way to a dark eternity, as though they were wending gallantly to a bridal feast! Who can see so great a wretchedness, and not long to cure it? Then, again, sin caused all that Passion, all these Sorrows. Perhaps one heart in the heat of love forgets itself, and thinks for the moment that by hindering sin it can spare our dearest Lord some pain. Yet is this altogether a mistake? is it quite an unreality? Anyhow, it will busy itself with reparation, and there is no reparation like the conversion of a sinner. And the lost sheep shall be laid at Mary's feet, and she shall gently raise them and lay them in the outstretched arms of the happy Shepherd; and we will sit down and weep for joy that we have been allowed to do something for Jesus and Mary; and we will ask no graces for ourselves, but only seek glory and love and praise for them. He who is growing in devotion to the Mother of God is growing in all good things. His time cannot be better spent; his eternity cannot be more infallibly secured. But devotion is, on the whole, more a growth of love than of reverence, though never detached from reverence. And there is nothing about our Lady which stimulates our love more effectually than her dolors. In delight and fear we shade our eyes when the bright light of her Immaculate Conception bursts upon us in its heavenly effulgence. We fathom with awe and wonder the depths of her Divine Maternity. The vastness of her science, the sublimities of her holiness, the singularity of her prerogatives, fill us with joyful admiration united with reverential fear. It is a jubilee to us that all these things belong to our own Mother, whose fondness for us knows no bounds. But somehow we get tired of always looking up into the bright face of Heaven. The very silver linings of the clouds make our eyes ache, and they look down for rest and find it in the green grass of the earth. The moon is beautiful, gilding with rosy gold her own purple region of the sky, but her light is more beautiful to our homesick hearts when it is raining over field, and tree, and lapsing stream, and the great undulating ocean. For earth, after all, is a home for which one may be sick. So, when theology has been teaching us our Mother's grandeurs in those lofty unshared mysteries, our devotion, because of its very infirmity, is conscious to itself of a kind of strain. Oh, how, after long meditation on the Immaculate Conception, love gushes out of every pore of our hearts when we think of that almost more than mortal queen, heart-broken, and with blood-stains on her hand, beneath the Cross! O Mother! we have been craving for more human thoughts of thee; we have wanted to feel thee nearer to us; we can weep for joy at the greatness of thy throne, but they are not such tears as we can shed with thee on Calvary; they do not rest us so. But when once more we see thy sweet, sad face of maternal sorrow, the tears streaming down thy cheeks, the quietness of thy great woe, and the blue mantle we have known so long, it seems as if we had found thee after losing thee, and that thou wert another Mary from that glorious portent in the heavens, or at least a fitter mother for us on the low summit of Calvary, than scaling those unapproachable mountain-heights of Heaven! See how the children's affections break out with new love from undiscovered recesses in their hearts, and run round their newly-widowed mother like a river, as if to supply her inexhaustibly with tears, and divide her off with a great broad frontier of love from the assault of any fresh calamity. The house of sorrow is always a house of love. This is what takes place in us regarding Mary's dolors. One of the thousand ends of the Incarnation was God's condescending to meet and gratify the weakness of humanity, forever falling into idolatry because it was so hard to be always looking upward, always gazing fixedly into inaccessible furnaces of light. So are Mary's dolors to her grandeurs. The new strength of faith and devotion, which we have gained in contemplating her celestial splendors, furnishes us with new capabilities of loving; and all our loves, the new and the old as well, rally round her in her agony at the foot of the Cross of Jesus. Love for her grows quickest there. It is our birthplace. We became her children there. She suffered all that because of us. Sinlessness is not common to our Mother and to us. But sorrow is. It is the one thing we share, the one common thing betwixt us. We will sit with her therefore, and sorrow with her, and grow more full of love, not forgetting her grandeurs,---oh, surely never!---but pressing to our hearts with fondest predilection the memory of her exceeding Martyrdom. What is the wise life but that which is for ever more living over again the Thirty-Three Years of jesus? What is all else but a waste of time, a cumbering of the world, a taking up room on earth which men have no right to? We should ever be in attendance upon some one or other of the mysteries of Jesus, steeping our thoughts in it, acting in the spirit of it. Our blessed Lord's interior dispositions are the grand practical science of life, and the sole science which will carry away any of time's products into eternity. The way in which we should both learn and exercise this science is by pondering on the mysteries of Jesus, or indeed by faith personally assisting at them in the spirit of Mary. This imitation of Mary must be the lifelong attitude of Christians. She read off our Lord's Sacred Heart continually. She saw habitually, as in a glass before her, all His inward dispositions, whether they regarded His Father, herself, or us. There were times when He drew a veil over it; but, ordinarily speaking, that vision was abidingly before her. So say the Agredan revelations. But even if this were not so, who can doubt that Mary understood Jesus as no one else could do and was in closer and more real union with Him than any Saint could be? Hence, no one doubts that her sympathy with Him in all His mysteries was of the most perfect description, and in keeping with her consummate holiness. We must, therefore, learn her heart. We must strive to enter into her dispositions. An interior life, taken from hers, faint and disfigured as the copy at best must be, is the only one which is secure from manifold delusion. Yet nowhere can we penetrate so deeply into her heart, or be so sure of our discoveries, as in the case of her sorrows. Moreover, the field for participation in the spirit of Jesus which they open to us is wider; for, immense as was His joy, nay, even perpetually beatific, His life was distinguished rather by sorrow than by joy. Sorrow was, so to speak, more intimate to Him than joy. Joy was the companion of the Thirty-Three Years; sorrow was their character, their instrument, their energy, their discovery of what they were to seek. Thus, a participation in the spirit of Jesus through the spirit of Mary is the true spirit of this devotion to our Lady's Dolors. Those who have lived for some years amid their quiet shadows can tell how they are almost almost a revelation in themselves. But when we speak of the spirit of this devotion, we must not omit to speak also of its power. We must not dwell exclusively on the spiritual effects it produces on ourselves, without reminding ourselves of its real power with God. In this respect one devotion may differ from another. One may be more acceptable to God, even where all are acceptable. He may promise prerogatives to one which He has not promised to another. Now there are few devotions to which our blessed Lord has promised more than He has done to this. There is a perfect cloud of visions and revelations resting upon it, and, in consequence, of examples of the Saints also. Moreover, there are reasons for its being so, in the nature of the devotion itself. We know what a powerful means of grace our Blessed Lady is, and our devotion to her must for the most part take its form either from her sorrows or her joys. Now, in her joys, as St. Sophronius says, our Lady is simply a debtor to her Son, whereas in her sorrows He is in some sense a debtor to her. St. Methodius, the Martyr, teaches the same doctrine. Hence, if we may dare to use words which holy writers have used before, by her dolors she has laid our blessed Lord under a kind of obligation, which gives her a right and power of impetration into which something of justice even enters. Yet when we think of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, of the immensity of His love for Mary, and of the great part of the Passion which it was to Him to see her suffer, we cannot for a moment doubt, without thinking of obligation, the extreme persuasiveness to Him of devotion to her' dolors, a devotion which He Himself began, a devotion which was actually a solid part of His ever-blessed Passion. We draw Him toward us the moment we begin to think of His Mother's sorrows. He is beforehand, says St. Anselm, with those who meditate His Mother's woes. And do we not stand in need of power in Heaven? What a great work we have to do in our souls, and how little of it is already done! How slight is the impression we have made yet on our ruling passion, on our besetting sin! How superficial is our spirit of prayer, how childishly timid our spirit of penance, how transitory our moments of union with God! We want vigor, determination, consistency, solidity, and a more venturous aspiration. In short, our spiritual life wants power. And here is a devotion so solid and efficacious, that it is eminently calculated to give us this power, as well by its masculine products in the soul as by its actual influence over the Heart of our Blessed Lord. Who, that looks well at the saints, and sees what it has done for them, but will do his best to cultivate this devotion in himself? In the affairs of this world steadiness comes with age. But who has not felt that it is not so in spiritual things? Alas! fervor is steadiness there, and that is too often but for a while; when we have held on upon our way for some years, we grow tired. Familiarity brings with it the spirit of dispensation. Our habits become disjointed, as if the teeth of the wheels were worn down and would not bite. Our life gets uneven and untrue, like a machine out of order. So we find that the longer we persevere, the more we stand in need of steadiness. For behold! when we had trusted to the doctrine of habit, and dreamed that age would bring maturity in its own right, the very opposite has been the case. In easy ways, and low attainments, and unworthy condescensions, and the facility of self-dispensing indulgence, in a word, in all things that are second best, the power of habit is strong enough, indeed altogether to be depended on. But in what is best, in effort, in climbing, in fighting, in enduring, in persisting, we seem to grow more uncertain, fitful, capricious, irregular, feeble, than we were before. A worse weakness than that of youth is coming back to us,---worse because it has less hopefulness about it, worse because time was to have cured the old weakness, and now it is time which is bringing this weakness on,---worse because it makes us less anxious, for we have hardened ourselves to think that we attempted too much when we were young, and that prudence indicates a low level, where the air is milder and better for our respiration. Then do not some of us feel that the world grows more attractive to us as we grow older? It should not be so; but so it is! This comes of lukewarmness. Age unlearns many things; but woe betide it when it unlearns vigor, when it unlearns hope! Rest is a great thing. It is the grand want of age. But we must not lie down before our time! Ah! how often has fervent youth made the world its bed in middle life! and when at last the world slipped from under it, whither did it fall? If we live only in the enervating ring of domestic love, much more in the vortex of the world, we must live with Jesus in the spirit of Mary, or we are lost. Let us learn this in increased devotion to her dolors. When we lie down to rest, we persuade ourselves it is but for a moment, and that we shall not go to sleep. But only let this most pathetic romance which the destinies of humanity have ever brought before men sound in our ears and knock at the doors of our hearts, and it will become in us a continually-flowing fountain of supreme unworldliness. Torpor will become impossible. Oblivion of supernatural things will be unknown. We shall feel that rest would be pleasant for a while; but we shall disdain the temptation. Mary will teach us to stand beneath the Cross. |

E-MAIL

E-MAIL

HOME-------BACK TO THE SORROWS OF MARY--------THE PASSION

www.catholictradition.org/Passion/cross1-7.htm