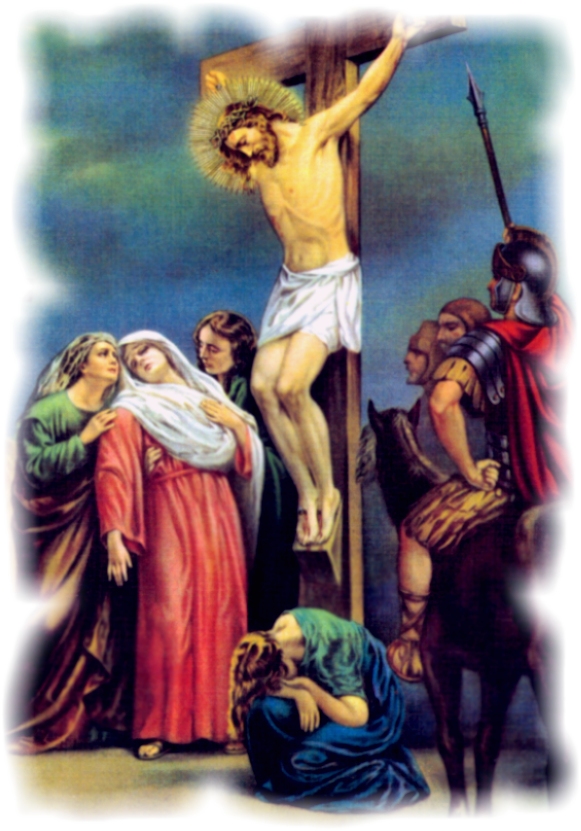

THE FIFTH DOLOR

THE CRUCIFIXION

THE world is a mystery. Life, time, death, doubt, good and evil, and

the uncertainty which hangs about our eternal lot, are all mysteries.

They lie burning on the heart at times. But the Crucifix is the meaning

of them, the solution of them all. It puts the question, and answers it

as well. It is the reading of all riddles, the certainty of all doubts,

and the centre of all faiths, the fountain of all hopes, the symbol of

all loves. It reveals man to himself, and God to man. It holds a light

to time that it may look into eternity and be reassured. It is a sweet

sight to look upon in our times of joy; for it makes the joy tender

without reproving it, and elevates without straining it. In sorrow

there is no sight like it. It draws forth our tears, and makes them

fall faster, and so softly that they become sweeter than very smiles.

It gives light in the darkness, and the silence of its preaching is

always eloquent, and death is life in the face of that grave earnest of

eternal life. The Crucifix is always the same, yet ever varying its

expression so as to be to us in all our moods just what we most want

and it is best for us to have. No wonder saints have hung over their

Crucifixes in such trances of contented love. But Mary is a part of the

reality of this symbol. The Mother and the Apostle stand, as it were,

through all ages at the foot of the Crucifix, symbols themselves of the

great mystery, of the sole true religion, of what God has done for the

world which He created. As we cannot think of the Child at Bethlehem

without His Mother, so neither will the Gospel let us picture to

ourselves the Man on Calvary without His Mother also. Jesus and Mary

were always one; but there was a peculiar union between them on

Calvary. It is to this union we now come, Mary's fifth dolor, the

Crucifixion.

The Way of the Cross was ended, and the summit of the mount has been

attained a little before the hour of noon. If tradition speaks truly,

it was a memorial place even then, fit to be a world's sanctuary; for

it was said to be the site of Adam's grave, the spot where he rested

when the mercy of God accepted and closed his nine hundred years of

heroic penance. Close by was the city of David, which was rather the

city of God, the centre of so much wonderful history, the object of so

much pathetic Divine love. The scene which was now to be enacted there

would uncrown the queenly city; but only to crown, with a far more

glorious crown of light, and hope, and truth, and beauty, every city of

the world where Christ Crucified should be preached and the Blessed

Sacrament should dwell. It was but a little while, an hour perhaps,

since the last dolor; so that only four hours have elapsed between the

fourth dolor and the consummation of the fifth. Yet in sorrow and in

sanctification it is a longer epoch than the eighteen years of

Nazareth. In nothing is it more true, than in our sanctification, that

with God a thousand years are but one day. These hours were filled with

mysteries so Divine, with realities so thrilling, that the lapse of

time is hardly an element in the agony of Mary's soul. She comes to the

Crucifixion a greater marvel of grace, a greater miracle of suffering,

than when an hour ago she had met the Cross-laden Jesus at the corner

of the street.

They have stripped Him of His vestments, from the shame of which

stripping His Human Nature shrank inexpressibly. To His Mother the

indignity was a torture in itself, and the unveiled sight of Her Son's

Heart the while was a horror and a woe words cannot tell. They have

laid Him on the Cross, a harder bed than the Crib of Bethlehem in which

He first was laid. He gives Himself into their hands with as much

docility as a weary child whom his mother is gently preparing for his

rest. It seems, and it really was so, as if it was His own will, rather

than theirs, which was being fulfilled. Beautiful in His disfigurement,

venerable in His shame, the Everlasting God lay upon the Cross, with

His eyes gently fixed on Heaven. Never, Mary thought, had He looked

more worshipful, more manifestly God, than now when He lay outstretched

there, a powerless but willing victim; and she worshipped Him with

profoundest adoration. The executioners now lay His right arm and hand

out upon the Cross. They apply the rough nail to the palm of His Hand,

the Hand out of which the world's graces flow, and the first dull knock

of the hammer is heard in the silence. The trembling of excessive pain

passes over His sacred limbs, but does not dislodge the sweet

expression from His eyes. Now blow follows blow, and is echoed faintly

from somewhere. The Magdalen and John hold their ears; for the sound is

unendurable; it is worse than if the iron hammer were falling on their

living hearts. Mary hears it all. The hammer is falling upon her living

heart; for her love had long since been dead to self, and only lived in

Him. She looked upward to heaven. She could not speak. Words would have

said nothing; The Father alone understood the offering of that heart,

now broken so many times. To her the Nailing was not one action. Each

knock was a separate martyrdom. The hammer played upon her heart as the

hand of the musician changefully presses the keys of his instrument.

The Right Hand is nailed to the Cross. The Left will not reach. Either

they have miscalculated in the hole they have drilled to facilitate the

passage of the nail, or else the Body has contracted through agony.

Fearful was the scene which now ensued, as the saints describe it to us

in their revelations. The executioners pulled the left arm with all

their force; still it would not reach. They knelt against His ribs,

which were distinctly heard to crack, though not to break, beneath the

violent pressure, and, dislocating His arm, they succeeded in

stretching the Hand to the place. Not more than a gentle sigh could be

wrung from Jesus, and the sweet expression in His eyes dwelt there

still. But to Mary,---what imagination can reach the horror of that

sight, of that sound, to her? Oh, there was more grief in them than has

gone to the making of all the Saints that have ever yet been canonized!

Again the dull blows of the hammer commence, changing their sounds

according as it was flesh and muscle, or the hard wood, through which

the nail was driving its cruel way. His legs are stretched out also by

violence; one Foot is crossed upon another, those Feet which have so

often been sore and weary with journeying after souls; and through the

solid mass of shrinking muscles the nail is driven, slowly and with

unutterable agony, because of the unsteadiness of the Feet in that

position. It is useless to speak of the Mother; it is idle to

compassionate her. Our compassion can reach no way, in comparison of

the terrible excess of her agony. But God held His creature up, and she

lived on.

Now the Cross is lifted off from the ground, with Jesus lying on it,

the same sweet expression in His eyes, and is carried near to the hole

which they have dug to receive the foot. They then fasten ropes to it,

and, edging it to the brink of the hole, they begin to rear it

perpendicularly by means of the ropes. When it is raised almost

straight up, they work the foot of it gradually over the edge of the

cavity until it jumps into its socket with a vehement bound, which

dislocates every bone, and nearly tears the Body from the nails.

Indeed, some contemplatives mention a rope fastened round His waist

with such cruel tightness that it was actually hidden in the flesh, to

hinder His Body from detaching itself from the Cross. So one horror

outstrips another, searching out with fiery thrills, like the

vibrations of an earthquake, all the supernatural capabilities of

suffering, which lay like abysses in the Mother's ruined heart: Let us

not compare her woe to any other. It stands by itself. We may look at

it and weep over it in love, in love which is suffering as well. But we

dare not make any commentary on it. Sorrowful Mother! Blessed be the

Most Holy Trinity for the miracles of grace wrought in thee at that

tremendous hour!

Earth trembled to its very centre. Inanimate things shuddered as if

they had intelligence. The rocks were split around, precipices cloven

all along the most distant shores of the Mediterranean, and the

mystical veil of the temple rent in twain by the agitation of the

earth, as if a hand had done it. At that moment,---so one revelation

tells us---there rose up from the temple-courts a long wailing blast of

trumpets, to mark the offering of the noonday sacrifice, and they that

blew the trumpets knew not how, that day, they rang in heaven as the

noonday trumpets never rang before. Darkness began to creep over the

earth; for the satellite of earth might well eclipse the material sun,

when the earth itself was thus eclipsing the Sun of justice, the

Eternal Light of the Father. The animals sought coverts where they

might hide. The songs of the birds were hushed in the gardens beneath.

Horror came over the souls of men, and the beginnings of grace, like

the first uncertain advances of the stealthy dawn, came into many

hearts out of that sympathetic darkness. A moment was an age when men

were environed by such mysteries as these.

The first hour of the three begins,---the three hours that were such

parallels to the three days when she was seeking her lost Boy. In the

darkness she has come close up to the Cross; for others fell away, as

the panic simultaneously infected them. There is a faith in the Jews,

upon which this fear can readily graft itself. But the executioners are

hardened, and the Roman soldiers were not wont to tremble in the

darkness. Near to the Cross, by the glimmering light, they are dicing

for His garments. The coarse words and rude jests pierced the Mother's

heart; for, as we have said before, it belonged to her perfection that

her grief absorbed nothing. Every thing told upon her. Every thing made

its own wound, and occupied her, as if itself were the sole suffering,

the exclusively aggravating circumstance. She saw those

garments---those relics, which were beyond all price the world could

give---in the hands of miserable sinners, who would sacrilegiously

clothe themselves therewith. For thirty years they had grown with our

Lord's growth, and had not been worn by use,---renewing that miracle

which Moses mentions in Deuteronomy, that, through all the forty years

of the desert, the garments of the Jews were not "worn out, neither the

shoes of their feet consumed with age." Now sinners were to wear them,

and to carry them into unknown haunts of drunkenness and sin. Yet what

was it but a type? The whole of an unclean world was to clothe itself

in the beautiful justice of her Son. Sinners were to wear His virtues,

to merit by His merits, to satisfy in His satisfactions, and to draw,

at will, from the wells of His Precious Blood. As Jacob had been

blessed in Esau's clothing, so should all mankind be blessed in the

garments of their elder Brother.

Then there was the seamless tunic she herself had wrought for Him. The

unity of His Church was figured there. She saw them cast lots for it.

She marked to whom it had fallen. One of her first loving duties to the

Church will be to recover it for the faithful as a relic. Then it was

that the history of the Church rose before her. Every schism, which

ever should afflict the Mystical Body of her Son, was like a new rent

in her suffering heart. Every heresy, every quarrel, every unseemly sin

against unity, came to her with keenest anguish, there on Calvary, with

the living Sacrifice being actually offered, and the unity of His

Church being bought with so terrible a price. All this bitterness

filled her soul, without distracting her from Jesus for a single

moment. As holy pontiffs, with hearts broken by the wrongs and

distresses of the Church, have been all engrossed by them, yet never

for an instant lost their interior union with Jesus, so much more was

it with His Mother now. It was on Calvary she felt all this with an

especial feeling, as it is in Lent, and Passiontide, and in devotion to

the Passion, that we learn to love the Church with such sensitive

loyalty.

Fresh fountains of grief were opened to her in the fixing of the title

to the Cross. It had come from Pilate, and a ladder was set up against

the Cross, and the title nailed above our Saviour's Head. Every blow of

the hammer was unutterable torture to Him, torture which had a fearful

echo also in the Mother's heart. Nor was the title itself without power

to extend and rouse her suffering. The sight of the Holy Name blazoned

there in shame to all the world---the Name, which to her was sweeter

than any music, more fragrant than any perfume,---this was in itself a

sorrow. The name of Nazareth, also, how it brought back the past,

surrounding the Cross, in that dim air, with beautiful associations and

marvelous contrasts. Everywhere in the Passion Bethlehem and Nazareth

were making themselves felt, and seen, and heard, and always eliciting

new sorrow from the inexhaustible depths of the Mother's heart. If He

was a king, it was a strange throne on which His people had placed Him.

Why did they not acknowledge Him to be their king? Why did they wait

for a Roman stranger to tell it them as if in scorn? Why did they not

let Him rule in their hearts? Ah! poor people! how much happier would

it be for themselves, how many sins would be hindered, how many souls

saved, how much glory gained for God! King of the Jews! would that it

were so! Yet it was really so. But a king rejected, disowned, deposed,

put to death! What a load lay upon her heart at that moment! It was the

load of self invoked curses, which was to press to the ground that poor

regicide people. She would have borne all her seven dolors over again

to abolish that curse, and reinstate them, as of old, in the

predilection of the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. It was too late.

They had had their day. They had filled up the measure of their

iniquity. It rose to the brim that very morning, and the breaking of

Mary's heart was a portion of their iniquity. But at least over her

heart Jesus was acknowledged king, and reigned supreme. So was it with

the dear Magdalen and the ardent John; and, as she thought of this, she

looked upon them with a very glory of exceeding love. Is it that Jesus

breaks the hearts over which He reigns, or that He comes of special

choice to reign in broken hearts? But as the sense passed over her of

what it was to have Jesus for a king,---of the undisputed reign which

by His own grace He exercised over her sinless heart,---of the vastness

of that heart, far exceeding by his own bounty the grand empire of the

Angels or the multitudinous perfections of the Saints,---and of the

endless reign which He would have in that beautiful "ivory palace" of

hers which made Him so glad,---her love burst out afresh upon Him, as

if the dikes of ocean had given away, and the continents were being

flooded with its waters, and every gush of love was at the same time an

exquisite gush of pain.

She had enough of occupation in herself. But sorrow widens great

hearts, just as it contracts little ones. She had taken to herself the

thieves for sons. She was greedy of children. She felt the value of

them then, in the same way in which we know the value of a friend when

we are losing him. His dead face looks it into us, and means more than

his living expression did. She has wrestled in prayer for those two

malefactors, and God has given her to see the work of grace beginning

in the heart of one of them. Does this content her? Yes! with that

peculiar contentment which comes of answered prayer, that is to say,

she became more covetous because of what she had not. She counted that

only for a beginning. She pleaded, she insisted. One would have thought

such prayer at such a time resistless. It is not Heaven that resists.

Graces descend from above like flights of Angels to the heart of the

impenitent thief. They fluttered there. They sang for entrance. They

waited. They pecked at the heart of flesh. They made it bleed with

pain, with terror, with remorse. But it was its own master. It would

not open. So near Jesus, and to be lost! It might well be incredible to

Mary. Yet so it was. The thief matched his hardness against her

sweetness, and prevailed. Mary may not be queen of any heart where

Jesus is not already king. But, oh, the unutterable anguish to her of

this impenitence! His face so near the Face of Jesus, the sighs of the

spotless victim dwelling in his ear as silence dwells in the mountains,

the very Breath of the Incarnate God reaching to him, the Precious

Blood strewn all around him, like an overflow of waste water, as if

there was more than men knew what to do with, and in the midst of all

this to be damned, to commute the hot strangling throes of that

crucifixion for everlasting fire, to be detached by his own will from

the very side of the Crucifix, and the next moment to become a part of

hopeless Hell! Mary saw his eternity before her as in a vista. She took

in at a glance the peculiar horror of his case. There came a sigh out

of her heart at the loss of this poor wretched son, which had sorrow

enough in it to repair the outraged majesty of God, but not enough to

soften the sinner's heart.

Such were the outward, or rather let us call them the official,

occupations of Mary during the first hour upon the Cross. Her inmost

occupation, and yet outward also, was that which was above her,

overshadowing her in the darkness, and felt more vividly even than if

it had been clearly seen,---Jesus hanging upon the Cross! As our

guardian Angels are ever by our sides, engrossed with a thousand

invisible ministries of love, and yet all the while see God, and in

that one beatifying sight are utterly immersed, so was it with Mary

upon Calvary. While she seemed an attentive witness and listener of the

men dividing our Lord's garments among them, and of the nailing of the

title to the Cross, or appeared to be occupied with the conversion of

the thieves, she did all those things, as the saints do things, in

ecstasy, with perfect attention and faultless accuracy, and yet far

withdrawn into the presence of God and hidden in His light. A whole

hour went by. Jesus was silent. His Blood was on fire with pain. His

Body began to depend from the Cross, as if the nails barely held it.

The Blood was trickling down the wood all the while. He was growing

whiter and whiter. Every moment of that agony was an act of worship

fully worthy of God Himself. He was holding ineffable communion with

the Father. Mysteries, exceeding all mysteries that had ever been on

earth, were going on in His Heart, which was alternately contracted and

dilated with agony too awful for humanity to bear without miraculous

support. It had Divine support; but Divine consolation was carefully

kept apart. The interior of that Heart was clearly disclosed to the

Mother's inward eye, and her heart participated in its sufferings. She,

too, needed a miracle to prolong her life, and the miracle was worked.

But with the same peculiarity. From her, also, all consolation was kept

away. And so one hour passed, and grace had created many worlds of

sanctity, as the laden minutes went slowly by, one by one, then slower

and slower, like the pulses of a clock at midnight when we are ill,

beating sensibly slower to reproach us for our impatient listening.

The second hour began. The darkness deepened, and there were fewer

persons round the Cross. No dicing now, no disturbance of nailing the

title to the Cross. All was as silent as a sanctuary. Then Jesus spoke.

It seemed as if He had been holding secret converse with the Father,

and He had come to a point when He could keep silence no longer. It

sounded as if He had been pleading for sinners, and the Father had said

that the sin of His Crucifixion was too great to be forgiven. To our

human ears the word has that significance. It certainly came out of

some depth, out of something which had been going on before, either His

own thoughts, or the intensity of His pain, or a colloquy with the

Father. "Father! forgive them; for they know not what they do!"

Beautiful, unending prayer, true of all sins and of all sinners in

every time! They know not what they do. No one knows what he does when

he sins. It is his very knowledge that the malice of sin is past his

comprehension which is a great part of the malice of his sin. Beautiful

prayer also, because it discloses the characteristic devotion of our

dearest Lord! When He breaks the silence, it is not about His Mother,

or the apostles, or a word of comfort to that affectionate forlorn

Magdalen,  whom He loved so

fondly. It is for sinners, for the worst of them, for His personal

enemies, for those who crucified Him, for those who had been yelling

after Him in the streets, and loading Him with the uttermost

indignities. It is as if at Nazareth He might seem to love His Mother

more than all the world beside, but that now on Calvary, when His agony

had brought out the deepest realities and the last disclosures of His

Sacred Heart, it was found that His chief devotion was to sinners. Was

Mary hurt by this appearance? Was it a fresh dolor that He had not

thought first of her? Oh, no! Mary had no self on Calvary. It could not

have lived there. Had her heart cried out at the same moment with our

Lord's, it would have uttered the same prayer, and in like words would

have unburdened itself of that of which it was most full. But the word

did draw forth new floods of sorrow. The very sound of His voice above

her in the obscure eclipse melted her heart within her. The marvel of

His uncomplaining silence was more pathetic now that He had spoken.

Grief seemed to have reached its limits; but it had not. That word

threw down the walls, laid a whole world of possible sorrow open to it,

and poured the waters over it in an irresistible flood. The

well-remembered tone pierced her like a spear. The very beauty of the

word was anguish to her. Is it not often so that deathbed words are

harrowing because they are so beautiful, so incomprehensibly full of

love? Mary's broken heart enlarged itself, and took in the whole world,

and bathed it in tears of love. To her that word was like a creative

word. It made the Mother of God Mother of mercy also. Swifter than the

passage of light, as that word was uttered, the mercy of Mary had

thrown round the globe a mantle of light, beautifying its rough places,

and giving lustre in the dark, while incredible sorrow made itself

coextensive with her incalculable love. whom He loved so

fondly. It is for sinners, for the worst of them, for His personal

enemies, for those who crucified Him, for those who had been yelling

after Him in the streets, and loading Him with the uttermost

indignities. It is as if at Nazareth He might seem to love His Mother

more than all the world beside, but that now on Calvary, when His agony

had brought out the deepest realities and the last disclosures of His

Sacred Heart, it was found that His chief devotion was to sinners. Was

Mary hurt by this appearance? Was it a fresh dolor that He had not

thought first of her? Oh, no! Mary had no self on Calvary. It could not

have lived there. Had her heart cried out at the same moment with our

Lord's, it would have uttered the same prayer, and in like words would

have unburdened itself of that of which it was most full. But the word

did draw forth new floods of sorrow. The very sound of His voice above

her in the obscure eclipse melted her heart within her. The marvel of

His uncomplaining silence was more pathetic now that He had spoken.

Grief seemed to have reached its limits; but it had not. That word

threw down the walls, laid a whole world of possible sorrow open to it,

and poured the waters over it in an irresistible flood. The

well-remembered tone pierced her like a spear. The very beauty of the

word was anguish to her. Is it not often so that deathbed words are

harrowing because they are so beautiful, so incomprehensibly full of

love? Mary's broken heart enlarged itself, and took in the whole world,

and bathed it in tears of love. To her that word was like a creative

word. It made the Mother of God Mother of mercy also. Swifter than the

passage of light, as that word was uttered, the mercy of Mary had

thrown round the globe a mantle of light, beautifying its rough places,

and giving lustre in the dark, while incredible sorrow made itself

coextensive with her incalculable love.

The words of Jesus on the Cross might almost have been a dolor by

themselves. They were all of them more touching in themselves than any

words which ever have been spoken on the earth. The incomparable beauty

of our Lord's Soul freights each one of them with itself, and yet how

differently! The sweetness of His Divinity is hidden in them, and for

ages on ages it has ravished the contemplative souls who loved Him

best. If even to ourselves these words are continually giving out new

beauties in our meditations, what must they be to the saints, and then,

far beyond that, what were they to His Blessed Mother? To her, each of

them was a theology, a theology enrapturing the heart while it

illumined the understanding. She knew they would be His last. Through

life they had been but few, and now in less than two hours He will

utter seven, which the world will listen to and wonder at until the end

of time. To her they were not isolated. They recalled other unforgotten

words. There were no forgotten ones. She interpreted them by others,

and others again by them, and so they gave out manifold new meanings.

Besides which, she saw the interior from which they came, and therefore

they were deeper to her. But the growing beauty of Jesus had been

consistently a more and more copious fountain of sorrow all through the

Three-and-Thirty Years. It was not likely that law would be abrogated

upon Calvary. And was there not something perfectly awful, even to

Mary's eye, in the way in which His divine beauty was mastering every

thing and beginning to shine out in that eclipse? It seemed as if the

Godhead were going to lay Itself bare among the very ruins of the

Sacred Humanity, as His bones were showing themselves through His

flesh. It was unspeakable. Mary lifted up her whole soul to its

uttermost height to reach the point of adoration due to Him, and

tranquilly acknowledged that it was beyond her power. Her adoration

sank down into profusest love, and her love condensed under the chill

shadow into an intensity of sorrow, which felt its pain intolerably

everywhere as the low pulsations of His clear gentle voice rang and

undulated through her inmost soul.

The thought which was nearest to our Blessed Saviour's Heart, if we may

reverently venture to speak thus of Him, was the glory of His Father.

We can hardly doubt that after that, chief among the affections of the

created nature which He had condescended to assume, stood the love of

His Immaculate Mother. Among His seven "lords there will be one, a word

following His absolution of the thief at Mary's prayer, a double word,

both to her and of her. That also shall be like a creative word,

creative for Mary, still more creative for His Church. He spoke out of

an unfathomable love, and yet in such mysterious guise as was fitted

still more to deepen His Mother's grief. He styles her "Woman," as if

He had already put off the filial character. He substitutes John for

Himself, and finally appears to transfer to John His own right to call

Mary Mother. How many things were there here to overwhelm our Blessed

Lady with fresh affliction! She well knew the meaning of the mystery.

She understood that by this seeming transfer she had been solemnly

installed in her office of second Eve, the mother of all mankind. She

was aware that now Jesus had drawn her still more closely to Himself,

had likened her to Himself more than ever, and had made their union

more complete. The two relations of Mother and Son were two no longer;

they had melted into one. She knew that never had He loved her more

than now, and never shown her a more palpable proof of His love, of

which, however, no proof was wanting. But each fresh instance of His

love was a new sorrow to her; for it called up more love in her, and

with more love, as usual, more sorrow.

But what a strange Annunciation it was, this proclamation to her of the

Maternity of men, compared with the Annunciation of her Divine

Maternity! The midnight hour, the silent room, the ecstatic prayer, the

lowly promptitude of the consent, the swift marvel of the adorable

mystery,---all these were now exchanged for the top of Calvary in the

dun light of the eclipse, with her Son hanging bleeding on the Cross.

Oh, what surpassing joy went with the first Motherhood, what

intolerable anguish with the second! Yet while God sent His angel to

make the first Annunciation, He Himself, with His sweet Human voice,

condescended to make the second. But in Mary's soul there was the same

tranquility, in her will the same alacrity of devout consent. When we

are in deep sorrow, every action, which we are constrained to do, seems

to excite and multiply our grief. Even the very movements of body

disturb the stillness of the soul. An interruption, an external noise,

the scene that meets the uplifted eye, these are sufficient to burst

the bounds, and throw the mass of bitter waters once more over the

soul. So when Mary's whole nature rose to meet this word of Jesus, and

threw itself into the consent she gave, and turned her forcibly as it

were from Jesus to John, it was as if the whole anguish of the

Crucifixion gained a new life, a fresh activity, a more potent

bitterness, a more desolating power. The thought of Him, while it was

the most terrible of all her thoughts, was also the most endurable. She

felt most, when other thoughts usurped, the place of that. Who has not

felt this in times of mourning? He whom we have lost is our most

terrible thought. Yet there is a softness, a repose, in thinking of

him. The thought sustains our grief. But to think of other people, of

other things, brings with it a rawness, a disquietude, an irritable

dissatisfaction, an inopportune diversion, which makes our grief

intolerable. So now Jesus Himself brought sinners uppermost in Mary's

mind. He turned her thoughts from Himself to the Church, to His

enemies, His persecutors, His murderers. He unsphered her, so to speak,

from the sweet circle of her Motherhood, and placed her in the new

centre of her office and official relation to mankind. For, even when

He spoke to her and of her, it was still rather sinners than herself,

which seemed to be uppermost in His affections. The suffering of all

this was immense, worse than any other woe which that prolific morning

had brought her yet. So the second hour upon the Cross elapsed, an age

of wonders which ages of angelical science and seraphic contemplation

cannot adequately fathom. Jesus still lived; the Blood was still

flowing; the Body still growing whiter in the eclipse; the silence

tingling all around, except when His beautiful words trembled lightly

on the air, deepening, as it seemed, both the darkness and the

silentness.

The third hour began, the third epoch in which this long dolor was

working at the grand world of Mary's heart. His first word in this last

hour was worse than Simeon's sword to our dearest Mother. He said, "I

thirst," Well might He thirst. Since the blessed chalice of His own

Blood the night before, nothing had crossed His lips but the taste of

wine and gall, the pressure of the sponge with vinegar against His

mouth, and His own Blood which had trickled in, Meanwhile the nails

were burning like fires in His Hands and Feet; His limbs from head to

foot had been scorched with the thongs and prickles of the brutal

flagellation; endless thorns were sticking like spikes of flame through

His skull, until His brain throbbed with the intolerable inflammation,

Drop by drop His Blood had been drawn from Him, with all the moisture

of His Body, and the fountains in the Heart were on the very point of

failing. Surely we may well believe that there was never thirst like

His, No shipwrecked sufferers have ever burned with a more agonizing

thirst, or have ever pined and died with tongue and lips and throat

more dry and parched, than His, Yet we know that single torture has

been enough with strong men to sweep reason from its throne, and that

there are few deaths men can die more horrible than death from thirst.

We cannot doubt that our Blessed Lord suffered it beyond the point when

without miracle death must have supervened. How fearful must have been

the pressure of that physical suffering, which caused that

silence-loving Sufferer to exclaim! If ever it was marvelous that in

all her woe Mary had displayed no signs of feminine weakness, no

fainting, no sobbing, no outcry, no wild gesture of uncontrollable

misery, it was doubly marvelous now. Not only was this exclamation of

Jesus a most heart-rending grief to her, but there came upon it that

burden which human grief can never bear, and a grief of mother least of

all, the feeling of impotence to allay the agony of those we love. She

looked into His dying Face with a face on which death was almost as

deeply imprinted as on His. She saw His parched, swollen, quivering

lips, white with that whiteness of the last mortal struggle, which is

like no other whiteness. But she could not reach, not even to wipe with

her veil the Blood that was curdled there. It was vain, and she knew

it, to appeal to the cruel men that were scattered about the mount. For

a cup of cold water to those lips, through what new scenes of sorrow

would she not be eager to pass! But it might not be. She remembered how

He had once looked down into the cold sparkling water of Jacob's well,

and longed in His fatigue and thirst for one draught of that element

which He Himself had created, and then how He had forgotten both thirst

and weariness in His loving labor of converting that poor Samaritan

woman. But now---and it was an overwhelming thought---water was as far

from the lips of the dying Saviour as it was from those of Dives in the

endless fires out of which he had appealed if it were but for a single

drop. No! Her dearest Son must bear it. He has at last complained of

His physical tortures. But of what use was it except to break His

Mother's Heart again, and to call forth the love and adoration of

countless souls through ages and ages of His Church? To Him it brought

no relief. It was for our sakes that He complained, that, even at the

expense of more agony to Mary, we might have. one additional motive to

love our Crucified Brother.

But this was not the only thirst that word was intended to convey. His

Soul thirsted as feverishly for souls as His Body did for the water of

the well. He brooded over all coming ages, and yearned to multiply the

multitudes of the redeemed. Alas! we have approximations by which we

can measure His torment of physical thirst; but we have no shadow even

by which we can guess of the realities of that torment in His Soul. If

the love, which the Creator has for creatures, whom He had called out

of nothing, is unlike any other love either of Angels or of men, if its

kind is without parallel, and its degree an excess out of the reach of

our conception, so also is the spiritual love of souls in the Soul of

the Saviour of the world. Saving love is without similitude, as well as

creative love. As all the loves of earth are but sparks of creative

love so all apostolic instincts, all missionary zeal, all promptitude

of martyrdom, all intercessory penance, and all contemplative

intercession, are but little sparks of that saving love of which

Calvary is at once the symbol and the reality. The torment of this

thirst was incomparably beyond that of the other thirst. Mary saw it;

and no sooner had she seen it, than the very sight translated her, as

it were, into a fresh, unexplored world of sorrow. She saw that this

thirst would be almost as little satisfied as the other. She saw how

Jesus at that moment was beholding in His Soul the endless procession

of men, unbroken daily from dawn to dawn, bearing with them into hell

the character of baptism and the seal of His Precious Blood. See! even

now, while the Saviour is dying of thirst, the impenitent thief will

not give Him even his one polluted soul to drink! So was it going to be

ever more. Mary saw it all. Why had He ever left Nazareth? Why had He

gone through all this world of unnecessary suffering, only to succeed

so inadequately at last? Was God's glory, after all, the end of

Calvary, rather than the salvation of men? Yes! and yet also No! Mary,

like Jesus Himself, grudged not one pang, one lash, one least drop of

Blood that beaded His crowned brow. She too thirsted for souls, as He

did, and her heart sank when she saw that He was not to have His fill.

Oh, poor, miserable children that we are! How much of our souls have we

not kept back, which would have somewhat cheered both the Mother and

the Son that day!

But Jesus had to go down into an abyss of His Passion deeper than any

which He had sounded hitherto. Into that deep Mary must go down also.

Not merely for us was the word He was now to utter. It is beyond us. It

comes like a mysterious far off cry out of the depths of spiritual

anguish, to which even mystical theology can give no name. It is God

abandoned of God,---the creature rejected of the Creator, although

united to Him by a Hypostatic Union,---the Sacred Humanity abandoned by

the Divine Nature to which it is inseparably assumed,---a Human Nature

left Personless, because the Divine Person, who never can withdraw

Himself, has withdrawn,---the Second Person of the Holy Trinity

deserted by the Other Two! What wild words are these? We know they

cannot be, simply cannot. Yet when we put the dereliction of Jesus into

words, these are the impossible expressions in which we become

entangled. "My God! My God! why hast Thou forsaken Me?" Was there ever

a more truly created cry? Yet He who uttered it was Himself the

Creator. Not merely for us, then, could such a word be spoken. It was

wrung from Him by the very spirit of adoration in the extremity of His

torture. Some have conjectured that it was at that moment that the

hitherto unconsumed species of the Blessed Sacrament was consumed, and

so that mysterious union of Himself with Himself withdrawn. But this

does not recommend itself to us. Why should He derive comfort and

strength from His own sacramental Flesh and Blood, when He was exposing

both Flesh and Blood to unheard-of torments? Why derive comfort at all,

when He was studiously making all things round Him, even His Mother's

heart, fresh instruments of torture? Why should His Divine Nature in

the Blessed Sacrament be a sweetness and restorative to Him, the loss

of which extracted such a cry, when even in the Hypostatic Union, which

was an incomparably closer union than that of the Blessed Sacrament, He

was cutting off the supplies of His Divine Nature from His Human,

excepting the single communication of His Omnipotence to enable Him to

live, in order that He might suffer more? The sense of the

faithful---that instinct which so seldom errs---points without

hesitation to the Eternal Father, as the cause of that suffering, and

as addressed in that word.

But is there cruelty in God! No! Infinite justice is as far removed

from cruelty as infinite love can be. Yet it was the Father, He who

represents all kindness, all indulgence, all forbearance, all

gentleness, all patience, all fatherliness in heaven and earth, who

chose that moment of in tensest torture, when the storm of created

agonies was beginning to pelt less piteously, because it was now

well-nigh exhausted, to crucify afresh, with a most appalling interior

crucifixion, the Son of His own endless complacency. With effort

unutterably beyond all grace ever given, except the grace of Jesus,

Mary lifted up her heart to the Father, joined her will to His in this

dire extremity, and, in a certain sense, as well as He, abandoned her

Beloved. She gave up the Son to the Father. She sacrificed the love of

the Mother to the duty of the Daughter. She acknowledged the Creator

only as the last end of the creature. She had done this at the outset

in her first dolor, the Presentation of Jesus, and it was consummated

now. O Mother! how far that exacting glory of God led thy royal heart!

She saw Jesus abandoned. She heard the outcry of His freshly-crucified

Soul, pierced to the quick by this new invention of His Father's

justice. And she did not wish it other- wise. She would have Him

abandoned, if it was the Father's will. And it was His will. Therefore,

with all her soul, with the most unretracted, spontaneous consent, she

would have Him abandoned. She would go down from the top of Calvary

this moment if the Father bade her. But her love rose up, as if it were

desperate, to meet this uttermost exigency. No one would have dreamed

that a human soul could have held so much love as she poured out upon

Jesus at that moment. Was her heart in. finite, inexhaustible? It

really seemed so. For at that hour it combined, multiplied, outstripped

all the love of the Three-and-Thirty Years, and rushed into His soul as

if it would fill up with its own self the immense void which the

dereliction of the Father had opened there. Every thing went out of

her, but the horrible bitterness of her martyrdom. Sorrow---pure,

sheer, sharp, fiery sorrow---was flesh, and blood, and bone, and soul,

and all to her. All else was gone into the Heart of Jesus, which

thereupon sent forth upon her an outpouring of love, which deluged her

with a fresh ocean of overwhelming woe. And by one miracle they both

lived still.

Now, Blessed Mother, that thou standest on such incredible heights of

detachment, the end may come I It was finished. All was finished.

Chiefly creation. It had found a home at the grave of the First Adam

under the Cross of the Second. The Father had left Him. He must go to

the Father. It is impossible They should be disunited. Creatures had

done what they could. They had filled to the brim the Saviour's cup of

suffering, and He, with pitiable love, had drained it to the dregs. But

there was one created punishment still left, created rather by the

creature than the Creator, created chiefly by a woman. It was the

punishment of death, the eldest-born child of the first Eve. But could

death hold sway over the living Life of eternity? Could Eve punish God?

Was He to inherit the bitter legacy of the sweet Paradise? How could it

be? How could He die? What could death be like to Him? Mary's heart

must be lifted to the height of this dread hour. High as it is, it must

be raised higher still, to the level of this divinest mystery. The

Three-and-Thirty Years are ending. A new epoch in the world's history

is to open. The most magnificent of all its epochs is closing. What

will death be like to Him? Ah! we may ask also, what will life be like

to her when He is dead? What will Mary herself be like without Jesus?

She was not looking up, but she knew His eye was now resting on her.

What strange power is there in the eyes of the dying, that they often

turn round the averted faces that are there, and attract them to

themselves, that love may see the last of its love? His eye was resting

on the same object on which it rested the moment He was born, when He

lay suddenly on a fold of her robe upon the ground while she knelt in

prayer, and when He smiled, and lifted up His little hands to be taken

up into her arms, and folded to her bosom. His arms were otherwise

lifted up now, inviting us to climb up into them, like fond children,

and see what the embrace of a Saviour's love is like. She felt His eye,

and she looked up into His face. Never did two such faces look into

each other, and speak such unutterable love as this. The Father held

Mary up in His arms, lest she should perish under the load of love; and

the loud cry went out from the hilltop, hushing Mary's soul into any

agony of silence, and the Head drooped toward her, and the eye closed,

and the Soul passed her, like a flash, and sank into the earth, and a

wind arose, and stirred the mantle of darkness, and the sun cleared

itself of the moon's shadow, and the roofs of the city glimmered white,

and the birds began to sing, but only as if they were half reassured,

and Mary stood beneath the Cross a childless Mother. The third hour was

gone.

Such was the fifth dolor, with its creative periods of sanctity and

sorrow. She had stood through it all, notwithstanding the agonizing

yesterday, the sleepless night, the long morning crowded with its

terrible phenomena. In the strength of her unfailing weariness she had

stood through it all, and Scripture is careful to mark the posture, as

if this miracle of endurance was of itself a revelation of the

greatness of the Mother's heart. It is, as it were, a reward for her

dolor, that we cannot preach Christ Crucified unless Mary be in sight.

It is something else we preach---not that---unless she be standing

there. And now she stands on Calvary alone. It is three hours past noon

of the most awful day the world shall ever see.

Something still remains to be said of the peculiarities of this dolor,

notwithstanding that so much has been unavoidably anticipated in the

narrative. Above all things, the Crucifixion has this peculiarity, that

it was the original fountain of all the other dolors, except the third.

That stands apart. It is Mary's own Crucifixion, her Gethsemane and her

Calvary. But the two dolors which came out of the Infancy, and the four

which represent the Passion, have the Crucifixion for their centre. The

Three Days' Loss does not belong to the Infancy, and the shadow of the

Passion is no more thrown over it than it was over the whole life of

Mary. It was the act of Jesus Himself, which seemingly had an especial

relation to His Mother. The third dolor, which prefaces the Eighteen

Years at Nazareth, was to her sorrows what the Eighteen Years were to

her life generally, something between Jesus and herself, a mystery of a

different sphere from those in which both He and she were concerned in

the fulfillment of the world's redemption. But the sword in Simeon's

prophecy was the Crucifixion. The Flight into Egypt was to hinder the

cruelty of Herod from anticipating the moment of our Saviour's death.

The Meeting with the Cross was the road to Calvary. The Taking down

from the Cross, and the Burial, were sorrows which flowed naturally out

of the Crucifixion, and were in unbroken unity with it. The Crucifixion

was therefore the realization of her lifelong woe. The fountain was

reached. She had tracked it up to Calvary. What remained was the waste

water, or rather the water and blood, which flowed down from the mount,

and sank in at the threshold of the Garden Tomb. Compared with the

Crucifixion, the other dolors, the third always excepted, were almost

reliefs and distractions stirring on the fixed depths of her

unfathomable woe. The Crucifixion was a sorrow by itself, without name

or likeness. It was the centre of the system of her dolors, while the

independence of her third dolor betokens the existence of that vast

world which Mary is in her own self, a creation apart, brighter than

this world of ours, and more dear to Jesus. It is a mysterious orb

allowed to come in sight of this other system, where we are,---a

disclosure of all that world of phenomena which is hidden from our eyes

in the Eighteen Years, during which Jesus devoted Himself to her. It

ranks with the Immaculate Conception, the Incarnation, and the

Assumption, all which belong to Mary's world, and would have been even

if sin had not been, though they would have been different from what

they were. But that third dolor shows how the fallen world of sin and

the necessity of a passible Incarnation told on her world, as it did on

His, and passed upon the lineaments of the Maternity as well as upon

those of the Incarnation. There are certainly few mysteries in the

gospel which we understand less than the Three Days' Loss. Another

peculiarity of the Crucifixion is the length of time during which the

tide of suffering remained at its highest point without any sign of

ebbing. The mysteries, which filled the three hours, seem too

diversified for us to regard them, at least till we come to the

Dereliction, as rising from less to greater in any graduated scale.

They are rather separate elevations, of unequal height, standing linked

together like a mountain-chain. But the lowest of them was so immensely

high that it produced most im- measurable agony in her soul. The

anguish of death is momentary. The length of some of the most terrific

operations which can rack the human frame seldom exceeds a quarter of

an hour. Pain pushed beyond a certain limit, as in medieval torture, is

instantaneous death. In human punishments which are not meant to kill,

the hand of science keeps watch on the pulse of the sufferer. But to

Mary the Crucifixion was three hours, three long hours, of mortal

agony, comprising hundreds of types and shapes of torture, each one of

them intolerable in itself, each pushed beyond the limits of human

endurance unless supported by miracle, and each of them kept at that

superhuman pitch for all that length of time. When pain comes we wish

to lie down, unless madness and delirium come with it, or we are fain

to run about, to writhe, gesticulate, and groan. Mary stood upright on

her feet the whole weary while, leaning on no one, and not so much as

an audible sigh accompanied her silent tears. It is difficult to take

this thought in. We can only take it in by prayer, not by hearing or

reading.

It was also a peculiarity of the Crucifixion that it was a heroic trial

of her incomparable faith. Pretty nearly the faith of the whole world

was in her when she stood, with John and Magdalen, at the foot of the

Cross. There was hardly a particle of her belief which was not tried to

the uttermost in that amazing scene. Naturally speaking, our Lord's

Divinity was never so obscured. Supernaturally speaking, it never was

so manifest. Could it be possible that the Incarnate Word should be

subject to the excesses of such unparalleled indignities? Was the light

within Him never to gleam out once? Was the Wisdom of the Father to be

with blasphemous ridicule muffled in a white sack, and pulled about in

absurd, undignified helplessness by the buffooning guards of an

incestuous king? Was there not a point, or rather were there not many

points, in the Passion, when the limit of what was venerable and

fitting was overstepped? Even in the reserved narrative of the Gospels,

how many things there are which the mind cannot dwell on without being

shocked and repulsed, as well as astonished! Even at this distance of

time do they not try our faith by their very horror, make our blood run

cold by their murderous atrocity, and tempt our devotion to withdraw,

sick and fastidious, from the affectionate contemplation of the very

prodigies of disgraceful cruelty, by which our own secret sins and

shames were with such public shame most lovingly expiated? .Is not

devotion to the Passion to this day the touchstone of feeble faith, of

lukewarm love, and of self-indulgent penance? And Mary, more delicate

and more fastidious far than we, drank all these things with her eyes,

and understood the horror of them in her soul, as we can never

understand it. Think what faith was hers.

The Divine Perfections also suffered a strange eclipse in the Passion.

Sin was triumphant. Justice was condemned. Holiness was abandoned even

by the All-holy. Providence seemed to have withdrawn, as if under

constraint. God was trodden out, and creatures had creation to

themselves; nay, more than that, they had the Creator in their power.

There was no divine interference, just when it appeared most needed and

most natural. If men could have their own way then, surely they could

have it always. One while God looked passive, another while cruel. Oh,

it required angelic theology to reconcile the providence of that day

with the attributes of the Most High! Then the angels themselves might

be a trial of her faith. Were there such things, such beings, as

Angels? She had seen them so often she could not doubt it. She had seen

St. Michael but the night before, bending in adoration by the side of

Jesus in His agony, a glorious being, fit for that strange exceptional

mission of consoling the Son of God in His inconsolable distress. But

where was their zeal for the Incarnate Word, that grand grace by which

they had all been established in their final perseverance? Where were

the double-edged cherubic swords that guarded the entrance into Eden

from all but Henoch and Elias? Ah! there were legions of them pressing

forward, yet ever beaten back, like a storm cloud striving to plough

its way up against the wind, eager and burning, yet with difficult

obedience bending backward before the meek, admonishing eye of Jesus.

Then, again, who could have believed, when they saw the beauty of Jesus

and fathomed the depth of His prayer, as Mary only could see the one or

fathom the other, that Divine grace really had power to convert human

hearts? He was the very beauty of holiness. During His Passion men

themselves tore away every veil which humility and reserve could hang

about His sanctity. His humility, His sweetness, His patience, His

modesty, all stood disclosed with the fullest light upon them,

exercised openly and heroically in the midst of the grossest outrage.

And yet men were not won to Him! There were the guards who had fallen

backward in the garden the night before. There were those who had stood

nearest to Him during the scourging, those who had talked with Him as

Pilate had, those who had taken Him to Herod and brought Him back

again. There was the impenitent thief close by His side. Grace was

going out from Him every moment. His effectual prayer was incessant.

Mary's intercession itself was busily engaged. Yet, when the sun set on

Friday, how little visible harvest had all that grace gathered into its

garners! Never did anyone so walk by faith, simple, naked faith, as

Mary did that day. There was faith enough to save a whole world in her

single heart.

Another peculiarity of this fifth dolor is to be found in the seven

words which our Lord uttered from the Cross. They were as seven sharp

thrills in Mary's heart, reaching depths of the human soul to which our

griefs never attain. It was not only the well known accents of her

dying Son, with their association inconceivably heightened by the

circumstances in which they broke upon the stillness. It was not only

the exceeding beauty of the words themselves, disclosing, as death

sometimes does with men, an unexpected interior beauty in the soul. It

was not only that, like the unuttered music of poetry in a kindred

soul, they waked up in her the remembrances of other words of His, and

I gave light to many mysteries in her mind, and played skillfully !

upon the many keys and with the various stops of her wonderful

affections, saying, as they did to her, what they do not say to us, and

what we cannot so much as guess. But they were the words of God, such

words as are spoken of in the Epistle to the Hebrews,. "living and

effectual, and more piercing than any two-edged sword, reaching unto

the division of the soul and the spirit, of the joints also and the

marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intents of the heart," Such was

their operation in the heart of Mary, penetrating her as the blast of a

trumpet seems to penetrate the recesses of our hearing, and in their

subtlety and agile swiftness carrying grief into the crevices of her

nature, whither it could not else have reached. She was the broken

cedar, the divided flame of fire, the shaken desert of Cades, in the

twenty-eighth Psalm. "The Voice of the Lord is upon the waters; the God

of majesty hath thundered, the Lord upon many waters: The Voice of the

Lord in its omnipotence, the Voice of the Lord in its magnificence. The

Voice of the Lord breaketh the cedars; yea, the Lord shall break the

cedars of Libanus. The Voice of the Lord divideth the flame of fire.

The Voice of the Lord shaketh the desert, and the Lord shall shake the

desert of Cades."

We have already spoken of the parallel between the Crucifixion and the

Annunciation, which is another peculiarity of the fifth dolor, She

became our Mother just when she lost Jesus. It was, as it were, a

ceremonial conclusion to the Thirty-Three Years she had spent with Him

in the most intimate communion, and at the same time a solemn opening

of that life of Mary in the Church to which every Baptized soul is a

debtor for more blessings than it suspects, In the third dolor He had

spoken to her with apparent roughness, as if her office of Mother was

now eclipsed by the mission which His Eternal Father had trusted to

Him. In this fifth dolor He, as it were, merges her Divine Maternity in

a new motherhood of men. Perhaps no two words that he ever spoke to her

were more full of mystery than that in the temple, and now this one

upon the Cross, or ever caused deeper grief in her soul. They are

parallel to each other. With such a love of souls as Mary had,

immensely heightened by the events of that very day, the motherhood of

sinners brought with it an enormous accession of grief. The multitudes

that were then wandering shepherdless over the wide earth, the

ever-increasing multitudes of the prolific ages, all these she received

into her heart, with the most supernatural enlightenment as to the

malice of sin, the most keen perception of the pitiable case and

helpless misery of sinners, the clearest foresight of the successful

resistance which their free will would make to grace, and the most

profound appreciation of the horrors of their eternal exile amidst the

darkness and the flames of punishment. Our Lord's word effected what it

said. It made her the Mother of men, therefore, not merely by an

outward official proclamation, but in the reality of her heart. He

opened up there new fountains of inexhaustible love. He caused her to

love men as He loved them, as nearly as her heart could come to His.

He, as it were, multiplied Himself in the souls of sinners millions of

millions of times, and gave her love enough for all. And such love! so

constant, so burning, so eloquent, so far above all earthly maternal

love, both in hopefulness, tenderness, and perseverance! And what was

this new love but a new power of sorrow? We cannot rightly understand

Mary's sorrow at the Crucifixion under any circumstances, simply

because it is above us. But we shall altogether miss of those just

conceptions which we may attain to unless we bear in mind that she

became our Mother at the foot of the Cross, not merely by a declaration

of her appointment, but by a veritable creation through the effectual

word of God, which at the moment enlarged her broken heart, and fitted

it with new and ample affections, causing thereby an immeasurable

increase of her pains. It was truly in labor that she travailed with us

when we came to the birth. The bitterness of Eve's curse environed her

spotless soul unutterably in that hour of our spiritual nativity.

We must not omit to reckon also among the peculiarities of this dolor

that which it shares with the fourth dolor, and in which it stands in

such striking contrast to the sixth,---her inability to reach Jesus in

order to exercise her maternal offices toward Him. So changeful can

sorrow be in the human heart that the very thing which will minister

sorrow to her by the fulness of its presence in the Taking down from

the Cross is a sorrow to her here by its absence. But they have mourned

little, too little for their own good, who have not long since learned

to understand this contradiction. It is hard for a mother to keep

herself quiet by the deathbed of her son. Grief must be doing

something. The wants of the sufferer are the luxuries of the mourner.

The pillows must be smoothed again, the hair taken out of the eyes,

those beads of death wiped from the clammy brow, those bloodless lips

perpetually moistened, that white hand gently chafed, that curtain put

back to give more air, the weak eyes shielded from the light, the

bedclothes pressed out of the way of his difficult breathing. Even when

it is plain that the softest touch, the very gentlest of these dear

ministries, is fresh pain to the sufferer, the mother's hand can

scarcely restrain itself; for her heart is in every finger. To be quiet

is desolation to her soul. She thinks it is not the skill or the

experience of the nurse which dictates her directions, but her

hard-heartedness, because she is not that fair boy's mother; and

therefore she rebels in her heart against her authority, even if the

chances of being cruel I do in fact restrain her hands. Surely that

foam must be gathered from the mouth, surely that long lock of hair

must tease him hanging across his eye and dividing his sight, surely

that icy hand should have the blood gently, most gently, brought back

again. She forgets that the eye is glazed and sees no more, that the

blood has gone to the heart, and even the mother's hand cannot conjure

it back again. And so she sits murmuring, her sorrow all condensed in

her compulsory stillness. Think, then, what Mary suffered those three

long hours beneath the Cross! Was ever deathbed so uneasy, so

comfortless, as that rough-hewn wood? Was ever posture more torturing

than to hang by nails in the hands, dragging, dragging down as the dead

weight of the Body exerted itself more and more? Where was the pillow

for His Head? If it strove to rest itself against the Title of the

Cross, the crown of thorns drove it back again; if it sank down upon

His Breast, it could not quite reach it, and its weight drew the Body

from the nails. Slow streams of Blood crept about His wounded Body,

making Him tremble under their touch with the most painful excitement

and uneasiness. His eyes were teased with Blood, liquid or half

congealed. His Mouth, quivering with thirst, was also caked with Blood,

while His breath seemed less and less to moisten. There was not a limb

which was not calling out for the Mother's tender hand, and it might

not reach so far. There were multitudes of pains which her touch would

have soothed. O mothers! have you a name by which we may call that

intolerable longing which Mary had, to smooth that hair, to cleanse

those eyes, to moisten those dear lips which had just been speaking

such beautiful words, to pillow that blessed Head upon her arm, to ease

those throbbing hands and hold up for a while the soles of those

crushed and lacerated feet? It was not granted to her; and yet she

stood there in tranquility, motionless as a statue, not a statue of

indifference, nor yet of stupor and amazement, but in that attitude of

reverent adoring misery which was becoming to a broken-hearted creature

who felt the very arms of the Eternal Father round her, holding her up

to live, to love, to suffer, and to be still.

We must also remember that the abandonment of Jesus by His Father was

something to her which it cannot be to us. In religious mysteries we

are continually obliged to take words for things. We speak of the

Eternal Generation of the Son and of the Eternal Procession of the Holy

Spirit, but we cannot embrace the wisdom, the brightness, the love, the

tenderness, the pathos, if we may venture on the word, which those acts

of the Divine Life imply. Consequently the words do not call out in us

an intelligent variety of feelings and sentiments and emotions: we meet

them by a simple act of adoring love. Yet they mean more to theologians

than to uneducated Christians, more to saints than to theologians, more

to the blessed in heaven than to the Saints on earth. But according to

our knowledge so should be our love, and in heaven it is so. Thus,

while the dereliction of Jesus on the Cross fills our minds with a

sacred horror, we only see into it confusedly. We rather see that it is

a mystery, than in what the mystery consists. It is often the very

indistinctness of Divine things which enables us to endure them. Who

could live, if he realized what Hell is, and that every moment immortal

souls are entering there upon their eternity of most shocking and

repulsive punishment? We smell a sweet flower, and just then a soul has

been condemned. We watch with trembling love the elevation of the Host

and Chalice, and meanwhile the gates of that fiery dungeon have closed

on many souls. We lie down upon the grass, and look up at the white

clouds, dipping through the blue sky as if either had waves, and

catching the sun on their snowy shapes, and all the while hell is

underneath that grass, within the measurable diameter of the earth,

living, populous, unutterable, its roaring flames and countless sounds

of agony muffled by the soil that covers the uneasily-riveted crust of

the earth. What agony would this be, if our minds were equal to it, or

coextensive with its reality! Nay, if we realized it, as sometimes for

a moment we do realize it, we could not survive many hours, even if we

did not die upon the spot. For, if the guilt of one venial sin shown to

His Saint by God would have produced the immediate separation of body

and soul, unless He by miraculous interference had supported her, what

must the vision be of the countless enormities of Hell, with the

additional hideousness of final impenitence and the unspeakable horror

of its punishments! So, with this dereliction of our Blessed Lord, none

understood it as Mary did. The whole of the marvelous theology that was

in it was perhaps clear to her. At least she saw in it what no one

else, not even an angel, could see. Hence, while it called out in her a

variety of the most vivid emotions and most sensitive affections, it

also plunged her into fresh sorrow, by transferring all at once the

Passion of Jesus into another and more terrific sphere.

The universality of her suffering is also another peculiarity of the

fifth dolor and in this it was a sort of shadow of the Passion. Who can

number the variety of the pains which those three hours contained? What

portion of her sinless nature was not covered with its appropriate

suffering? There was no spot whereon a sorrow could be grafted where

the hand of God had not inserted one. She was as completely submerged

in grief as a fish is submerged in the great deep sea. The very

omnipresence of God round about her was to her an omnipresence of

suffering. As the fires that punish sin are so dreadfully efficacious,

because God intended their nature to be penal, so the supernatural

sorrows of our Blessed Mother on Calvary were fearfully efficacious,

because they were intended to carry suffering to the utmost limit which

the creature could bear, that so her holiness, her merits, and her

exaltation might exceed those of all other creatures put together,

except the created nature of her Son. There was not an inlet of anyone

of the senses down which pain was not flowing masterfully, like

clashing tides in a narrow gulf. There was not a faculty of her mind

which was not illuminated, or rather scorched, by a light which hurt

nature and gave it pain. Her affections had been cruelly immolated at

the foot of that altar on Calvary, one after another, and the zealous

Priest had not spared His victims. Her will was strained up to the

height of the most unheard-of consents, which the devouring justice of

God had demanded of her. Her soul was crucified. Her body was the

shrinking prey of her mental agony. Her feet were weary with standing,

her hands wet with His Blood, her eyes filled with her own. "How hath

the Lord covered with obscurity the daughter of Zion! Weeping, she hath

wept in the night, and her tears are on her cheeks. There is none to

comfort her among all of them that were dear to her. From above He hath

sent fire into my bones, and hath chastised me; He hath spread a net

for my feet; He hath turned me back; He hath made me desolate, wasted

with sorrow all the day long. The Lord hath taken all my mighty

men out of the midst of me. He hath proclaimed against me a time, to

destroy my chosen men. The Lord hath trodden the wine- press for the

virgin daughter of Juda. Therefore do I weep, and my eyes run down with

water, because the Comforter, the relief of my soul, is far from me. My

children are desolate, because the enemy hath prevailed. My heart is

turned within me, for I am full of bitterness. Abroad the sword

destroyeth; and at home there is death alike. O, all ye that pass by

the way! attend, and see if there be any sorrow like to my sorrow; for

He hath made a vintage of me, as the Lord spoke in the day of His

fierce anger!" [Lamentations, i]

Last of all, there was her inability to die with Him. Many a time, to

die with the dead would be the only true consolation of the bereaved.

One heart has been the light of life, the unsetting light of long years

of various fortune, bright in the blue sky of prosperity, brighter

still in the black clouds of adversity. Now that light is put out by

death. Why should we survive? Henceforth, what significance can there

be to us in life? That cold heart was the end of all our avenues. Every

prospect terminated there. We valued no past where that heart was not.

We saw no future in which it did not play its part. All our plans ended

there. The weight of our expectations was concentrated on that one

point, and now it has given way, and we are falling through, we know

not whither. Ah! this loss is truly the end of life, more truly far

than the mere physical dissolution of soul and body. The

Apostles---especially the quick, affectionate Thomas---wished to go and

die with Lazarus, simply because Jesus loved him so. Oh, surely we can

all remember days which were the world's end to us,---days which it

seemed impossible should have a morrow! There was a bed-laden with a

sad weight, with a beautiful terror---which was to us the end of time,

the edge of the world, the threshold of eternity. It had been long

looked for, and yet words would not tell how cruelly unexpected it came

at last. All our hopes, and fears, and loves were gathered up, as if

the Judge were coming then to settle them. Common things could not go

on after that. Daily duties must not recur. Habits were run out. It was

an end, an end of so much,---so much so cruelly ended. It was as

fearful to have no prospect as it is to have no hope; and therefore we

longed to lie down and die, on the same bed, and be buried in the same

grave, though it seemed strange that anyone should remain behind to

bury us, so completely did it seem a universal end. This is a wild

extremity of human grief. Our Lady's dolor was something else than

this. The end of the Thirty-Three Years was not like any other end. Her

Son was God. It all lies in that. Think, after that, of the unutterable

misery of the Mother's life protracted, when His was done. It will not

bear explaining. It cannot be explained. But we can feel it, below the

world from which words come; we can see it,---a light beyond the region

where thought can grasp things,---that actual sundering of Jesus and

Mary, the dissolution of that union which had been the world's divine

mystery for all those wonderful and wonder-peopled years! Which of us

can tell what grief is like, when it has gone beyond the point at which

it would kill us, and we only live by a miracle external to ourselves?

Such grief was our Mother's when our Lord breathed out His Soul into

His Father's hands.

But let us turn from the peculiarities of the fifth dolor to the

dispositions in which our Blessed Lady endured it. Yet the task of

describing these is impossible. We read the lives of the Saints, and

see in each one of them a peculiar inward sanctity, sometimes different

from that of all others that we know,--- sometimes congenial to the

spirit of another Saint,---sometimes, though not often, allowing itself

to be grouped in numerous classes. Many of the graces which we read of,

have no names in the nomenclature of the virtues of their kindred

dispositions. We wonder as we read. We are dazzled by the lights which

keep appearing in the beauties of holiness, in splendoribus sanctorum. Yet we

know that what we see is as nothing to that which we do not see. As the

Queen of the South said of Solomon, not the half is told. All that

comes to the surface is a mere indication of the depths which are

below, hardly enough to let us guess at the interior beauty which the

eye of God beholds in the saintly soul. But, if this is the case with

the" saints, how much more so is it with our Blessed Lady! It is

expressly said of her that the beauty of the king's daughter is all

within; and when our Lord, in the Canticle, describes her loveliness,

He adds twice over, "besides that which lieth hid within." It is,

therefore, impossible to speak worthily of the interior beauty of Mary.

As we have considered each dolor it has become more difficult to speak

of her dispositions. We are obliged to use common words for things

which are singular and only akin to what is common. The realities keep

rising taller and taller above the words, until these last almost

mislead us, instead of elucidating the subject, and we have to repeat

the same words for dispositions which have become different in the