OF THE PASSION:

St. Catherine of Siena

| St.

Catherine of Siena: Biography Adapted by Catholic Tradition from SAINT CATHERINE OF SIENA by Mother Frances A. Forbes, a nun of the Society of the Scared Heart in Scotland who was a convert and highly regarded by Cardinal Merry de Val, a close friend of Pope St. Pius X. Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur, 1913. Currently published by TAN BOOKS. Chapter 4 THE DISCIPLES  F

Catherine had enemies, she also had many friends. It was not only her

holiness that drew men and women of all classes to seek the company of

the poor dyer's

daughter of Siena, although there are few things so attractive as

sanctity. God had given her a wonderful eloquence and power to read the

inmost hearts of those with whom she came in contact. There was

something so winning about Catherine's personality that few could

resist her. At the same time, the simple wisdom with which, untaught as

she was, she could converse with the most learned men convinced them

that God Himself was her Teacher. F

Catherine had enemies, she also had many friends. It was not only her

holiness that drew men and women of all classes to seek the company of

the poor dyer's

daughter of Siena, although there are few things so attractive as

sanctity. God had given her a wonderful eloquence and power to read the

inmost hearts of those with whom she came in contact. There was

something so winning about Catherine's personality that few could

resist her. At the same time, the simple wisdom with which, untaught as

she was, she could converse with the most learned men convinced them

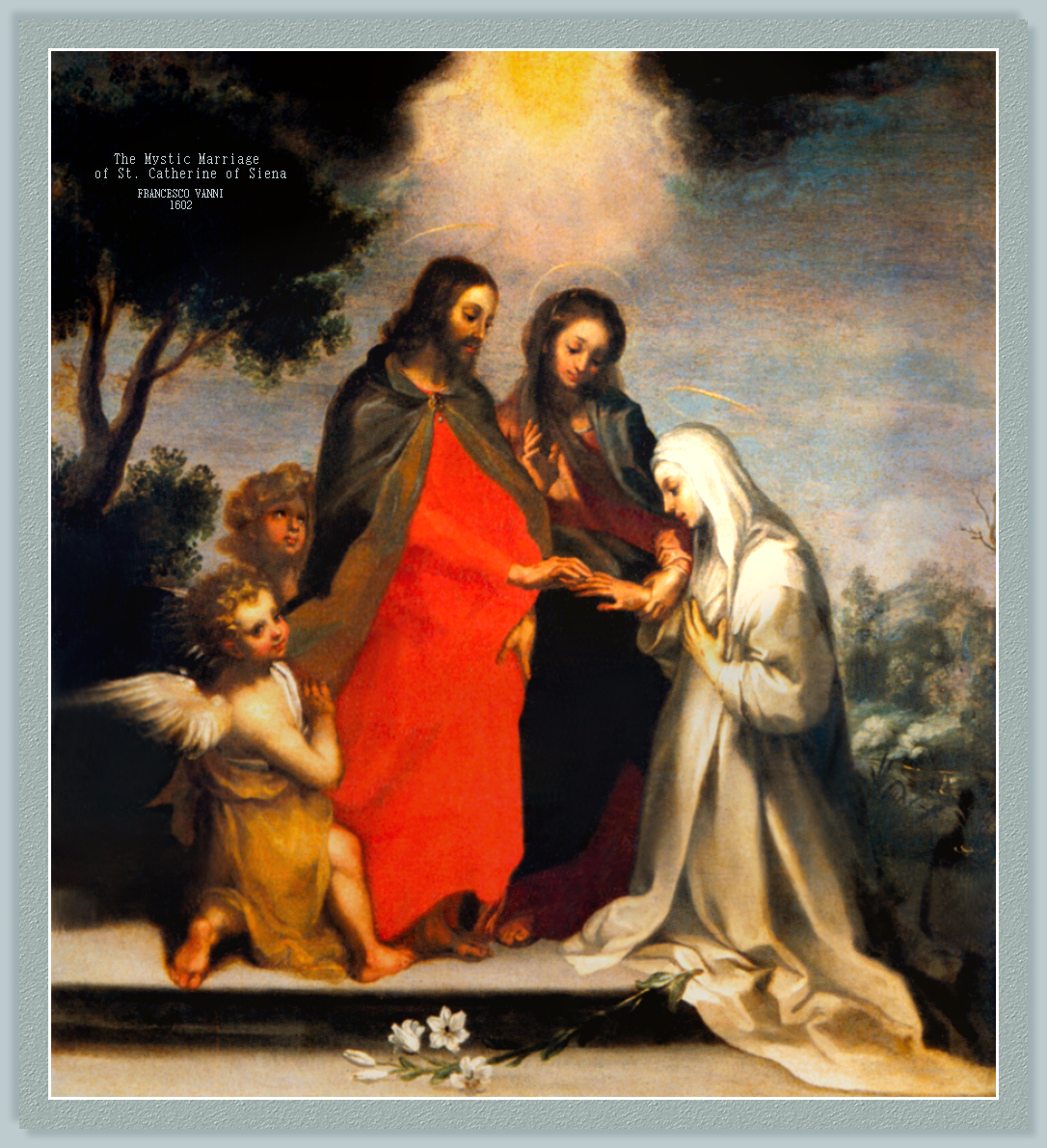

that God Himself was her Teacher.Her tender and loving heart, full of affection and sympathy for those who were in distress, was open to all God's creatures. In the ordinary matters of daily life she showed a homely common sense that astonished, no less than did her keen and merry sense of humor, those who expected to find in her nothing but an unpractical mystic lost in dreams and visions. Great as was her horror of sin, she was never known to shrink from the vilest sinners while there was any hope of winning them to better things. She saw the possibilities that lay hidden under the most unpromising exterior, and it was her unwavering belief in the existence of that "better self" in human nature, however fallen, that so often gave people strength and courage to overcome the "worse." During the time that she had been working among the sick and the poor in Siena, a little group of disciples had gathered round her, forming a spiritual family of which Catherine, young as she was, was not only the mother, but the very life and soul. Among these were several of the Mantellate or Dominican Sisters of Penance such as Alessia Saraceni, a young widow of noble birth who, in the early days of her friendship with Catherine, had given away all that she possessed to the poor, to serve Our Lord in poverty and penance. Lisa Colombini, Catherine's sister-in-law, who at her husband's death also became a a Sister of Penance, and Francesca Gori, or "Cecca," were among the most faithful of her female companions. There were also several Dominican friars who associated themselves with Catherine and looked to her for spiritual guidance, such as Fra Tommaso della Fonte, her first confessor; Fra Bartolommeo Domenico; Fra Antonio Caffarini, a learned man, who helped her in her study of the Scriptures; and Fra Raimondo of Capua, her third confessor and faithful friend, who became after her death Master General of the Dominicans and who wrote the famous Legenda or life of the Saint. Then there was Messer Matteo, rector of the great hospital called the Misericordia, where Catherine and her sisters often worked; and Andrea Vanni the painter, politician as well as artist, whose portrait of the Saint, painted from life, still hangs in the Church of St. Dominic. [The painting above.] Some whom Catherine had rescued from a life of sin, such as Francesco de Malevolti, a young nobleman of Siena, also joined the spiritual fellowship and gave themselves to the service of God. He was twenty-five years old when he was first introduced to her, "not a little fiery and daring," as he himself tells us, and leading a selfish and worldly life. Catherine read his heart and revealed to him his miserable condition, with the result that he determined to amend. But it takes time to overcome bad habits, and the change did not come in a day, as we gather from a letter of Catherine's written later from Avignon: "With the desire of finding thee again, my little lost sheep, and putting thee back into the fold with thy companions . . . Come, dearest son, I can well call thee dear, so much art thou costing me in tears and labors, and in much bitter sorrow." It is good to know that the letter had its desired effect and that Francesco took fresh courage for the fight and won the battle in the end. He often acted as Catherine's secretary and, after she had died, as he was widowed and had no children, he entered a monastery and died a holy death. Among the Saint's "spiritual family" were three young Tuscan noblemen. Tuscany is the region in the lower portion of northern Italy that contains both Siena and Florence; entire books have been published on the beauty of this region alone. There is a green serenity about its hills that surround the cities that evoke nobility itself. Neri di Landoccio, a Sienese poet, was the first of the three to attach himself to the service of Catherine and her ideals. He had a nervous, sensitive temperament, and was subject to moods of sadness and despondency. His life might have been tragic had not Catherine's strong religious spirit upheld him in his gloomier periods. Stefano Maconi was the second: young and gallant, he was well educated with a joyous outlook, a marked contrast to Neri. his devoted friend. Catherine loved him for his innocence of life and saw all the possibilities of holiness that lay in his character. Above all her spiritual sons, he was the one she most trusted; when she was absent he was the one the others looked to as the head of the "family". After the Saint's death, he joined the Carthusians and became the General of the Order. The circumstances of his meeting Catherine were occasioned because one of the most powerful families in Siena, the Tolomei, had a deadly feud with the Maconi and their friends. Stefano, who deplored this state of affairs, was advised to have recourse to the Saint who was known as a peacemaker. So Catherine arranged to have the members of both families meet her in the Church of San Cristoforo in the Piazza Tolomei, but when the time arrived, the Maconi and their friends were the only ones who kept the appointment. Catherine knelt down before the high altar. "They will not listen to me," she said, "but they will have to listen to God." Now it came to pass shortly afterward that the Tolomei and their friends, being close to the church, felt themselves impelled by a mysterious force to enter, and passing through the open door they found Catherine kneeling in ecstasy, surrounded by a strange and radiant light. Their hearts were softened at the sight, and then and there, before the altar, laying aside their hatred, they made peace with their foes. From that moment Stefano Maconi became Catherine's devoted friend. The third of the little group was Barduccio Carrigiani, who joined Catherine later in life and was greatly beloved by her on account of his purity of heart. He was with her in Rome when she died and only survived her a short time. "Whilst he was at his last breath," writes Fra Raimondo, "he began to laugh, and so with a laugh of joy he gave up the ghost, in such wise that the signs of that joyous laugh still appeared in his dead body. This thing, I think, befell because in his passing he beheld her whom in life he had loved with true charity of heart, robed in splendor, coming with gladness to meet him. There were monks and hermits too who visited the family from time to time and counted themselves among the number of Catherine's spiritual children. Not far from Siena was Lecceto, or the "Hermitage of the Woods." There lived William Flete, an Englishman from the University of Cambridge, and Giovanni Tantucci, better known as "John of the Cells," and a dear old hermit called Fra Santi, gentle and holy, who in his old age left the quiet of his cell to follow Catherine and work among the poor. Last, but not least, there was Catherine's mother, good Lapa, who also, after her husband's death, put on the habit of the Mantellate. She was known in the family as "Nonna" or "Granny" and lived to a great old age. A woman of the people, practical and sensible, she was not very spiritual, and she sometimes found it hard to understand the ways of her saintly daughter, for whom she nevertheless had the deepest reverence and affection. To love Catherine was, for all who approached her, to draw near to God. The love of the disciples for their spiritual mother was, as one of them expressed it, "kindled at the foot of the Cross and consecrated on the steps of the altar." They looked to her for strength and support, and she never failed them. To her each one was a gift from God's Own hand, and she never rested until she had drawn out the best that each had to give. "O sweetest Love," she prayed to her Divine Spouse, "let not the enemy snatch any one of them from my hands, but may all attain to Thee, O Eternal Father, to Thee Who art their final end." The state of things in Siena in the fourteenth century was in no way different from that of the other Italian republics. The nobles were always fighting among themselves or with the popolani (people) for the ruling power, and changes of government were frequent. The state prisons were filled with men who, justly or unjustly, were accused of treason and condemned to bear the penalty. Catherine had a special tenderness for criminals and would visit them in their dungeons. Even when they were condemned to death, she would go with them to the place of execution. Once when two poor wretches were passing the house where she was staying on their way to the scaffold, Alessia, hearing their blasphemies and screams of anguish-----for they were being tortured as they went-----called to Catherine. "O mother," she cried, "if ever you will see a pitiful sight, come now!" Catherine gave one look, and began to pray for the souls of the two poor criminals: "Remember the thief on the Cross, on whom Thou didst have mercy. Look down upon these wretched creatures, soften their hearts with the fire of Thy Holy Spirit, that they may be delivered from the second death." Our Lord heard Catherine's prayers, and when the thieves, still blaspheming, reached the gate of the city, He appeared to them, showing His precious Wounds streaming with the blood that had been shed for their salvation and assuring them of forgiveness if they repented of their sins. To the wonder of all who were present, the two men cried out for a priest and, having with deep sorrow of heart confessed themselves, went to their death in great peace and comfort. Many were the souls Catherine saved for her Divine Master in this way, but the most wonderful of all the conversions she effected was that of a young Perugian nobleman, Niccolo di Toldi, who had been sentenced to death. He had never practiced Catholicism, never even made his First Communion. When the priest, who was a friend of Catherine's, went to prepare him for death, the priest found him half mad with rage and despair and could do nothing with him. Catherine, hearing of what had passed, went at once to the prison. The poor young man, hardly more than a boy in years, was touched at once by her gentle words and clung to her as a child clings to its mother. She stayed with him, comforting and soothing him till he was ready for Confession. When she left the prison, Catherine promised to come again the next day and go with him to the place of execution. At break of day she returned, went to Mass with the poor prisoner and knelt beside him while he received Holy Communion for the first time in his life. "Take courage, my brother," she said, "for you are going to die washed in the adorable Blood of Jesus and with His sweet name on your lips." At this Niccolo was filled with strength and consolation so that he no longer feared to die; but Catherine went with him to the place of execution and, kneeling beside him, made the Sign of the Cross on his brow. There she remained, bending over him and speaking to him of God and of the life to come until the knife fell, when she received his head in her hands. Standing thus in ecstasy, with the blood of the young man flowing over her white robe, Catherine had a vision of his soul as it entered Heaven turning to her in the joy of that new birth with a radiant look of farewell. "And all who were present," says he who wrote the account of it, "watching that strange scene in a deep hush of devotion, felt as if they were assisting at the death of a martyr rather than that of a criminal." |

CONTACT

US

CONTACT

US

HOME---------------------------------------THE PASSION

www.catholictradition.org/Passion/siena4.htm