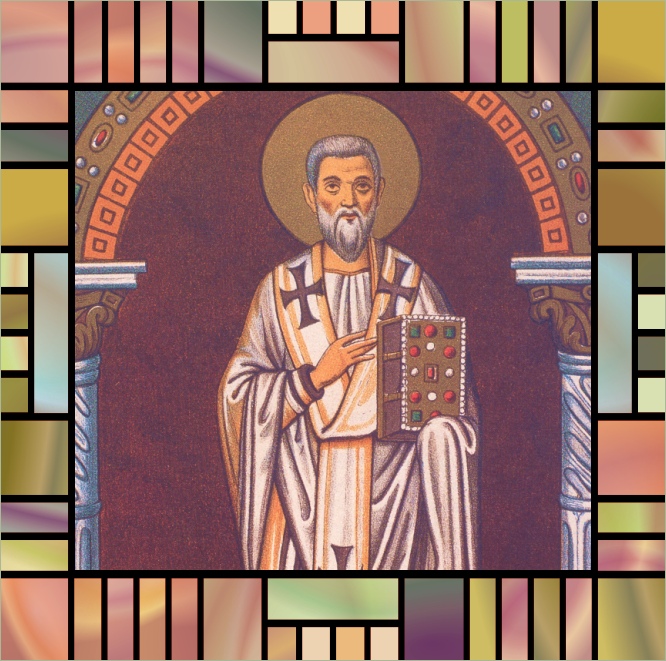

St. Gregory Nazianzen UNKNOWN ARTIST AND DATE  Saint Gregory

Nazianzen

St. Gregory who, from his profound skill in sacred learning, is surnamed the Theologian, was a native of Arianzum, an obscure village in the territory of Nazianzum, a small town in Cappadocia not far from Caesarea His parents are both honored in the calendars of the Church: his father on the 1st of January and his mother Nonna on the 5th of August. She drew down the blessing of Heaven upon her family by most bountiful and continual alms-deeds, in which she knew one of the greatest advantages of riches to consist; yet, to satisfy the obligation of justice which she owed to her children, she by her prudent economy improved at the same time their patrimony. The greatest part of her time she devoted to holy prayer; and her respect and attention to the least thing which regarded religion is not to be expressed. His father, whose name also was Gregory, was from his infancy a worshipper of false gods, but of the sect called the Hipsistarii, on account of the profession they made of adoring the Most High God. The prayers and tears of Nonna at length obtained of God the conversion of her husband, whose integrity in the discharge of the chief magistracy of his town and the practice of strict moral virtue prepared him for such a change. His son has left us the most edifying detail of his humility, holy zeal, and other virtues. He had three children, Gorgonia, Gregory, and Caesarius, who was the youngest. Gregory was the fruit of the most earnest prayers of his mother who, upon his birth, offered him to God for the service of his church. His virtuous parents gave him the strongest impressions of piety in his tender age; and his chief study, from his very infancy, was to know God by the help of pious books, in the reading whereof he was very assiduous. Having acquired grammar-learning in the schools of his own country, and being formed to piety by domestic examples, he was sent to Caesarea, in Palestine, where the study of eloquence flourished. He pursued the same studies some time at Alexandria, and there embarked for Athens in November. The vessel was beaten by a furious storm during twenty days, without any hopes either for the ship or passengers; all which time he lay upon the deck, bemoaning the danger of his soul on account of his not having been as yet Baptized, imploring the Divine mercy with many tears and loud groans, and frequently renewing his promise of devoting himself entirely to God in case he survived the danger. God was pleased to hear his prayer: the tempest ceased and the vessel arrived safe at Rhodes, and soon after at Aegina, an island near Athens. He had passed through Caesarea of Cappadocia in his road to Palestine; and making some stay there to improve himself under the great masters of that city, had contracted an acquaintance with the great St. Basil, which he cultivated at Athens, whither that saint followed him soon after. The intimacy between these two saints became from that time the most perfect model of holy friendship, and nothing can be more tender than the epitaph which St. Gregory composed upon his friend. Whilst they pursued their studies together, they shunned the company of those scholars who sought too much after liberty, and conversed only with the diligent and virtuous. They avoided all feasting and vain entertainments; and were acquainted only with two streets, one that led to the church and the other to the schools. Riches they despised and accounted as thorns, employing their allowance in supplying themselves with bare necessaries for an abstemious and slender subsistence, and disposing of the remainder in behalf of the poor. Envy had no place in them; sincere love made each of them esteem his companion's honour and advantage as his own; they were to each other a mutual spur to all good, and by a holy emulation neither of them would be outdone by the other in fasting, prayer, or the exercise of any virtue. Saint Basil left Athens first. The progress which St. Gregory made here in eloquence, philosophy, and the sacred studies appears by the high reputation which he acquired, and by the monuments which he has left behind him. But his greatest happiness and praise was, that he always made the love and fear of God his principal affair, to which he referred his studies and all his endeavours. The Emperor Constantius honoured him with his favour and made him his chief physician. His generosity appeared in this station by his practice of physic, even among the rich, without the inducement of either fee or reward. He was also a father to the poor, on whom he bestowed the greatest part of his income. Gregory was importuned by many to make his appearance at the bar, or at least to teach rhetoric, as that which would afford him the best means to display talents and raise his fortune in the world. But he answered that he totally devoted himself to the service of God. He entertained no secret affection for the things of this world, but trampled under his feet all its pride and perishable goods; finding no ardour, no relish, no pleasure but in God and in heavenly things. His diet was coarse bread, with salt and water. He lay upon the ground; wore nothing but what was coarse and vile. He worked hard all day, spent a considerable part of the night in singing the praises of God, or in contemplation. With riches he contemned also profane eloquence, on which he had bestowed so much pains, making an entire sacrifice of it to Jesus Christ. His classics and books of profane oratory he abandoned to the worms and moths. He regarded the greatest honors as vain dreams, which only deceive men, and dreaded the precipices down which ambition drags its inconsiderate slaves. Nothing appeared to him comparable to the life which a man leads who is dead to himself and his sensual inclinations; who lives as it were out of the world, and has no other conversation but with God. However, he for some time took upon him the care of his father's household and the management of his affairs. He was afflicted with several sharp fits of sickness, caused by his extreme austerities and continual tears, which often did not suffer him to sleep. He rejoiced in his distempers, because in them he found the best opportunities of mortification and self-denial. The immoderate laughter, which his cheerful disposition had made him subject to in his youth, was afterwards the subject of his tears. He obtained so complete a conquest over the passion of anger as to prevent all indeliberate motions of it, and became totally indifferent in regard to all that before was most dear to him. His generous liberality to the poor made him always as destitute of earthly goods as the poorest, and his estate was common to all who were in necessity, as a port is to all at sea. Never does there seem to have been a greater lover of retirement and silence. He laments the excesses into which talkativeness draws men, and the miserable itch that prevails in most people to become teachers of others. It was his most earnest desire to disengage himself from the

converse of men and the world, that he might more freely enjoy that of

heaven. He accordingly, in 358, joined St. Basil in the solitude into

which he had retreated, situate near the river Iris, in Pontus. Here,

watching, fasting, prayer, studying the holy scriptures, singing

psalms, and manual labour employed their whole time. The death of St. Basil, in 379, was to him a sensible affliction, and he then composed twelve epigrams or epitaphs to his memory; and some years after pronounced his panegyric at Caesarea, namely, in 381 or 382. The unhappy death of the persecuting emperor Valens, in 378, restored peace to the church. The Catholic pastors sought means to make up the breaches which heresy had made in many places. For this end they held several assemblies and sent zealous and learned men into the provinces in which the tyrant had made the greatest havoc. The Church at Constantinople was of all others in the most desolate and abandoned condition, having groaned during forty years under the tyranny of the Arians, and the few Catholics who remained there having been long without a pastor and even without a church wherein to assemble. They, being well acquainted with our saint's merit, importuned him to come to their assistance, and were backed by several bishops, desirous that his learning, eloquence, and piety might restore that church to its splendour. But such were the pleasures he enjoyed in his beloved retirement at Seleucia, and in his thorough disengagement from the world, that for some time these united solicitations made little or no impression on him. They had, however, at length their desired effect. His body bent with age, his head bald, his countenance extenuated with tears and austerities, his poor garb, and his extreme poverty made but a mean appearance at Constantinople; and no wonder that he was at first ill received in that polite and proud city. The Arians pursued him with calumnies, raillieries, and insults. The prefects and governors added their persecutions to the fury of the populace, all which concurred to acquire him the glorious title of confessor. He lodged first in the house of certain relations, where the Catholics first assembled to hear him. He soon after converted it into a church and gave it the name of Anastasia, or the Resurrection, because the Catholic faith, which in that city had been hitherto oppressed, here seemed to be raised, as it were, from the dead. St. Gregory had been obliged to govern the vacant see of Nazianzum after the death of his father, leaving the chief care of that Church to Cledonius in his absence. But in 382 he procured Eulalias to be ordained bishop of that city, and spent the remainder of his life in retirement near Arianzum, still continuing to aid that church with his advice, though at that time very old and infirm. In this private abode he had a garden, a fountain, and a shady grove, in which he took much delight. Here, in company with certain solitaries, he lived estranged from pleasures and in the practice of bodily mortification, fasting, watching, and praying much on his knees. "I live," says he, "among rocks and with wild beasts, never seeing any fire or using shoes; having only one single garment. I am the outcast and the scorn of men. I lie on straw, clad in sackcloth: my floor is always moist with the tears I shed."This great Saint looked upon the smiles and frowns of the world with indifference, because spiritual and heavenly goods wholly engrossed his soul. "Let us never esteem worldly prosperity or adversity as things real or of any moment," said he, "but let us live elsewhere, and raise all our attention to Heaven, esteeming sin as the only true evil, and nothing truly good but virtue, which unites us to God."

HOME---------------PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS-----------------LITANIES www.catholictradition.org/Saints/saints1-2.htm |