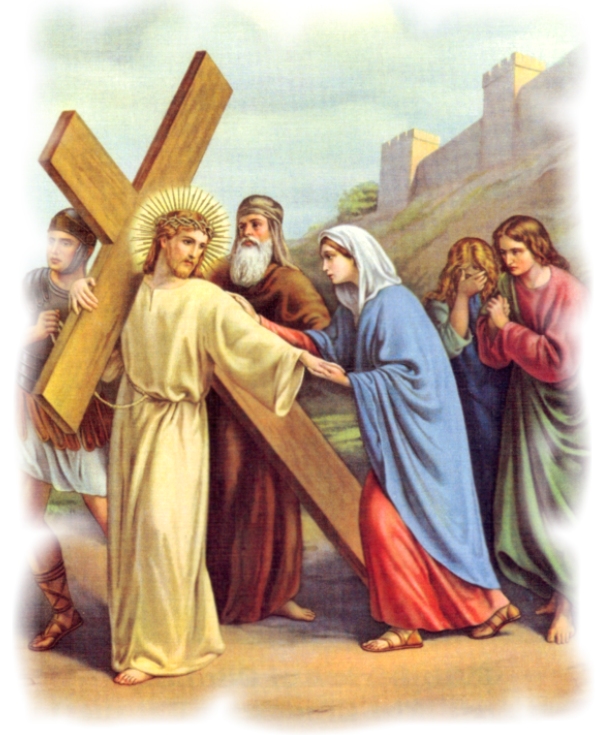

THE FOURTH DOLOR

MEETING JESUS WITH THE CROSS

WE have passed into a new world since the last

dolor. Bethlehem and Nazareth are left behind. We have bidden farewell

to the scenes of the Sacred Infancy, the Boyhood, and the Hidden Life.

The Three Years' Ministry has passed. It is twenty-one years since the

Three Days' Loss. The Immaculate Heart of Mary has traversed a world of

mysteries since then, always in supernatural joy, but always with her

lifelong sorrow lying on her soul. Henceforth we remain in Jerusalem,

which is the scene of her four last dolors, as it has been also of two

or three preceding. We have come to the morning of Good Friday, to her

meeting Jesus with the Cross, which is reckoned as her fourth dolor.

But, in order to understand the mystery rightly, we must make a

retrospect of the last twenty-one years. Mary is continually changing,

though it is only in one direction. Her life is an endless heavenward

ascension. She is always increasing in holiness, because she is always

increasing in love. She is always increasing in love, because Jesus is

always increasing in beauty. Thus each dolor found her at once less

prepared and better prepared: less prepared, because she loved Jesus

more, and it was in Him that she suffered; more prepared, because

stronger sanctity can carry heavier crosses. We saw before how the

augmentations of her love, from the Return from Egypt to her entry into

the gates of Jerusalem when they went up to our Lord's twelfth Pasch,

had increased her capabilities of suffering. So now the marvel of

sanctity, whom we left with her recovered Jesus in the house of

Nazareth, is very different from that heart which we are now to

accompany along the Way of the Cross. This fourth dolor was not in

itself equal to the third, but it fell upon greater capabilities of

suffering.

The beauty of the earthly paradise which God planted with His Own hand,

and whither He came at the hour of the evening breeze to converse with

His unfallen creatures, was a poor shadow of the loveliness of the Holy

House during the eighteen years of the Hidden Life. We cannot guess at

all the mysteries which were enacted within that celestial cloister.

The words were few, yet m eighteen years they were what we, our human

way, should call countless. The very silence even was a fountain of

grace.

There were tens of thousands of beautiful actions, each one of which

had such infinite worth that it might have redeemed the world. During

those eighteen years an immeasurable universe was glorifying God all

day and night. The beauty of the trackless heavens, swayed by their

majestic laws, vast unpeopled orbs with their processes of inanimate

matter or their seemingly interminable epochs of irrational life, earth

with all its inhabitants, the worshippers of the true God, amid

whatever darkness, in all its regions, the chosen flowers of the bygone

generations in Abraham's bosom in the limbus of the fathers, the little

children, a multitudinous throng of spirits, in their own receptacle

beneath the surface of the earth, the Souls worshipping amid the fires

of Purgatory,---all were swelling as in one concourse of creation the

glory of the Most High. The wide creation of Angels, above all,

peopling the immeasurable capacities of space, sent up to God ever

more, the God Whom they beheld clearly with the eyes of their

intelligence, a worship of the most exquisite perfection. But the

entire creation was as nothing to the Holy House of Nazareth.

One hour of that life outweighed ages of all the rest, and nor, only

outweighed it on a comparison, but outweighed it by a simple infinity.

There was the centre of all creation, spiritual or material, in nearly

the most sequestered village of that obscure Galilee. Why should the

centre be there? Who does not see that God's centres in all things

baffle the calculation of the sciences of men? There was a sense, too,

in which Mary seemed to be the centre of this central point of all

creation. For, if Jesus was the centre to Joseph and herself and the

countless ranks of wondering and adoring angels round, it appeared as

if she was the centre of Jesus, which was higher still. He had come to

redeem a whole world, and had allotted Himself but Three-and-Thirty

Years for the gigantic work. Twelve had been given to Mary. Some

shepherds had knelt before Him, three Eastern kings had kissed His

feet, Simeon had held Him in his arms, Anne had blessed Him, some

Egyptian infidels had wondered at Him, the townsfolk of Nazareth

thought Him no common Child. Otherwise the world knew nothing of Him.

He was one among many Galilean children. He had given Himself to Mary.

The twelve years ran out, and ended in the strangest mystery of grief.

It seemed as if it were a sort of initiation for Mary into some'

exalted regions of nameless sanctity. From that mystery there starts a

period of eighteen years, during which our Blessed Lord appears to

devote Himself exclusively to Mary and Joseph. It is as if He were her

novice-master, and she in a long novitiate, to be professed on Calvary.

It could not be waste of time. It could not be out of proportion with

the work of His Public Ministry, or with the suffering of His Passion.

It was in harmony with His wisdom. which was infinite. Just as the

Three Years' Ministry was the Jews' time, and the Passion our time, the

Eighteen Years were Mary's time.

Would it not be a hopeless task to make any calculations for the sake

of approaching to that sum of love which these years produced in Mary's

heart? The spiritual beauty of the Human Soul of Jesus, the contagion

of His heavenly example, the attraction of all His actions, the

efficacy of His superhuman words, the sight of His unveiled Heart, the

visions granted from time to time of His Divine Nature and of the

Person of the Word, were all so many fountains of substantial grace

flowing at all hours into Mary's soul. Without special assistance she

could not have lived in such vicinity to Him. She could not have

survived such a superangelic process of sanctification. Her life could

not have lived with her love. If there was any thing like a respite, if

we may so speak, in the eagle-flight of her soul, ever on and on, and

upward and upward, it was when she saw Jesus hanging His love on

Joseph, and arraying with new and incomparable graces that soul which

already in its grandeur surpassed all the Saints. Eighteen years with

God, knowing Him to be God, eighteen years of hearing, seeing,

touching, being touched by, and governing, the Creator of the universe!

Is it possible for languish to unveil the mysteries of such an epoch?

Which is the most imitable of God's attributes by us His

creatures? Strange to say, it is His holiness. So our Lord Himself

declares. We are to be perfect as God is perfect. The product, then, of

all these eighteen years in Mary's soul was sanctity, and, if sanctity,

therefore love. But by what means, in what ways, by the infusion of

what gifts, at what rate of speed, by what accelerated flights, what

mortal can so much as dream but they themselves, Mary and Joseph, on

whose souls God lay thus as it were upon a resting-place? If love

belonged only to angels and to men, we should have to give it some

other name when it reached the height it did in Mary. But God Himself

is love. So we have an infinity to move about in, and can call Mary's

sanctity by the name of love, without fear of uncrowning it of any of

its highest elevations. But if our Blessed Mother could in part with

Jesus at the gate of Jerusalem eighteen years ago, how will this new

universe of ten thousand different kinds of love of Him, which she

holds in her heart, allow her to part with Him now? This is the one

sense in which each dolor outstrips its predecessor, that it has more

love to torture, and therefore more power of inflicting pain. So much

power it has, that omnipotence must stand by to hold the life in that

dear heart, which is dearer to Him than all the world beside.

The Eighteen Years come to an end, and the Three Years' Ministry

begins. It is not clear to what extent our Blessed Lady was with Jesus

during His Public Ministry. Most probably she was never long separated

from Him. But Scripture affords us no decisive testimony on the point,

and contemplative saints have differed upon the subject. It seems most

likely it was not an actual separation from Him. If she was allowed to

follow Him through His Passion, we can hardly suppose she was ever far

removed from Him during His ministry. He began His miracles at her

intercession at Cana in Galilee, and when, on one occasion in the

Gospel, she comes to seek Him, as it were, with a Mother's rights, the

tone of the narrative would lead us to suppose that, on the one hand,

she was not continually with Him, and on the other that, although it

was no common thing her joining Him at times, she did so on occasions.

Under any circumstances, whether in spirit or through the revelations

of the Angels, or by some human channel, we cannot but suppose that she

was aware of all His sayings and doings during those three years. The

words of her Son can hardly be the common and accessible property of

all of us and not have been her portion also and a means of her further

sanctification.

To Mary the Three Years' Ministry was like a new revelation of Jesus.

She saw Him from many points of view from which she had never seen Him

before. Every variety in Him, however apparently trivial, could not be

really trivial, and was full of wonder, full of beauty, full of grace.

It was fresh food for love. It rung changes on the love which it drew

from the Mother's heart. In the Infancy she had seen Him, as it were,

in still life, giving out heavenly mysteries, as the fountain throbs

out water, with a seeming passiveness, though not unconsciously. In the

Boyhood, the wonders of His activity had developed themselves. Her

heart was taken captive afresh by His gracefulness. But He was with

those He knew, to whom He trusted Himself, whom He loved unspeakably.

He was at once the subject and the superior in the Holy House. But His

Ministry was almost a greater change upon His Hidden Life than His

Hidden Life had been upon His childhood. He had now to act out in the

world, to be God, yet not to seem singular, to adapt Himself to

numberless new positions, to address Himself to various classes of

hearers. At one while He was gently maturing the vocations of His

apostles, at another He was swaying multitudes, at another soothing

sorrow, at another rebuking sin. Now He was unfolding the Scriptures,

and unrolling the hidden folds of His deep parables to the chosen few;

now He was quietly and with easy wisdom eluding the snares of His

enemies, who had endeavored to entangle Him in His talk. Every day

brought its changes, its attitudes, its positions, its varieties. Every

side of His Human Nature was brought out. Endless graces were elicited.

It was like three years of heavenly music, rising and falling, changing

and interweaving, hushing and raising, winding and unwinding its

beautiful sounds for ever more. It was an indescribable combination of

sweetness and power, of wisdom and simplicity, of accommodation and

sanctity, of human and Divine. There was not, there could not be, a

trait, a tone, a gesture, a look, in the behavior of the Incarnate

Creator, which was not in itself at once a revelation to Mary, and, in

a lower degree, to the Angels also, and at the same time an

unfathomable depth which His own eye alone could sound. It was more

beautiful than the Infancy; it was more wonderful than the Hidden Life.

Its effect upon Mary must have been astonishing.

We shall never approach to a true view of her if we do not give the

Three Years' Ministry its due place in the stupendous process of her

sanctification. The epochs of her sanctification were mote wonderful

than the days of creation, and they are as distinctly marked. The

Immaculate Conception, with its fifteen years of growing merits, was

the first day. The Incarnation, with the twelve years of the Childhood,

occupied the second. The Three Days' Loss, with the eighteen years of

the Hidden Life, filled the third. The Three Years' Ministry occupied

the fourth. The Passion was the fifth. The Forty Days of the Risen

Life. with the descent of the Holy Ghost, engrossed the sixth. Then

came the seventh, our Lord's Sabbath, when He had ascended into Heaven,

and sat down at His Father's Right Hand. leaving the great world of

Mary's sanctity to go on for fifteen years, but, as in the case of the

material world, not without His ceaseless interference, and watchful

providence, and real presence, yet without His Hands working at it as

they did before. Then comes its end, her glorious death, her sweet

doom, her blissful resurrection, and His second Advent with His angels

to assume her into Heaven. We can never estimate the graces of our

Blessed Mother if we break up and disjoin these seven days of her

spiritual Genesis.

We must therefore consider the Three Years' Ministry as a most peculiar

time, during which, under the influence of the adorable changes of

Jesus, her love was growing, perhaps as it had never grown before. It

seems unreal to talk of new breadth "and depth and height, to that

which was beyond all, even angelic, measurements long ago. Years since,

her love had gone up so near to God, that the strong splendor of His

vicinity confused its outlines and proportions to our ineffectual eyes.

Nevertheless, we must speak so, hardly knowing what we mean. Mary

reached Bethany on the Thursday in Holy Week, loving Jesus with a love

which far surpassed the love she had for Him when the eighteen years of

the Hidden Life had come to a conclusion. St. Joseph was gone, and

although her love of him, ardent as it was, was no diversion from her

love of Jesus, but rather a variety of it, and an addition to it, yet

in some way, as all changes were with her, His death increased her love

of our Blessed Lord. The apostles had come into Joseph's place. She

knew all the secret designs of grace which our Lord had upon each of

them. She saw His way with them all through, in the variety of their

vocations and their gifts and their characters. It was a model to her,

who was one day to be the queen of those apostles. Her love of them

also in some way multiplied her love of Jesus. As in her other periods,

so in this, every thing which Jesus did was a fresh fountain of love

within her heart. His sermons, His parables, His secret teaching, His

austerities, His prayers, His tears, His miracles, His journeys, His

weariness, His hunger, His thirst, His contradictions,---each one of

them was an inexhaustible depth of love. So it was up to the eve of the

Passion. All this incalculable augmentation of love was, from our point

of view, a correspondingly increased capability of suffering. So the

end of the Ministry arrives, and the possibilities of her heart are

more wonderful than ever.

We seem to have wandered away from the dolor before us; but it is not

really so. The seven dolors are not seven separate mysteries, neither

can we understand them if we look at them in that way. They have a

unity of their own, and, if we detach them from that unity, we miss

their significance. They carry the whole of the Three-and-Thirty Years

along with them. Each of them depends for its truth, for its depth, for

its intensity, for its peculiar character, on a certain portion of

those years, inseparable from it. Jesus grows more beautiful. Grace

rises proportionately in Mary's soul. The growth of grace is the growth

of love. It reaches a certain point, known to God, fixed by Him,

capable of bearing a certain weight, of undergoing a given amount of

elevating and sanctifying sorrow; and at that point, as by the

operation of a law, one of the dolors comes, takes up the grace and

love of the preceding times, of years as in the childhood, of days as

in the swift Passion, compresses them into the most solid and sublime

holiness, flies away with the Mother's soul as if it had the strength

of all the Angels, and places her upon some new height, far away from

where she was before. Thus each dolor is a distinct sanctification to

her, a renewal, a transfiguration, another degree of Divine union. Then

the process begins again. Grace and love accumulate once more, with an

acceleration and a magnitude in proportion to her new height, until

once more, in the counsels of God, they reach the point where another

dolor comes to do its magnificent work. Thus also we have two

principles of comparison, by which we can contrast the dolors one with

another. First of all, they differ in themselves. Each has its peculiar

excess, like our Lord's sufferings in the Passion; and so each has its

own perfection and its own pre-eminence. They are all equally perfect,

but it is with a different and an appropriate perfection. The kind of

excess in one may be more afflictive than the kind of excess in

another. Thus it is that we call the third dolor the greatest. In this

sense they do not rise by degrees, each exceeding its predecessor, and

so culminating in a point. But there is a second sense in which they

do. Each dolor, as it comes, falls upon greater love, and also upon

love that has suffered more, and therefore upon a great capability of

suffering. In this way each is worse than its predecessor; and they go

on rising and rising in the terrible power of causing anguish, till the

very last, till the Burial of Jesus, till the possibilities of woe seem

to be exhausted, till the abysses of sanctifying sorrow contained in

the huge world of the Incarnation have been dried up by the absorption

of the single Immaculate Heart of the Mother of the Incarnate Word.

This is the unity of the dolors; and each dolor really means, not what

it looks like by itself, but what it is in the setting and order of the

Three-and-Thirty Years.

The Passion may be said to begin on the Thursday in Holy Week in the

house of Lazarus at Bethany. Mary, as might have been expected, opened

the long avenue of sorrows, great epochs in substance, though brief in

time. Jesus had entered Jerusalem on Palm Sunday in the modesty of His

well-known triumph. He had spent that day teaching in the temple, as

well as the following Monday and Tuesday, returning however to Bethany

at nights, as no one in Jerusalem had the courage to offer Him

hospitality, as the rulers were incensed with Him because of the recent

resurrection of Lazarus, and none of those who had cried Hosanna on

Sunday had the courage to put themselves forward individually and so

draw the resentful notice of the chief priests upon them. The Wednesday

He is supposed to have spent in prayer on the Mount of Olives, and to

have seen the elect of all ages of the world pass before Him in

procession, while He prayed severally for each. Judas meanwhile was

arranging his treachery with the rulers. It is supposed also that our

Blessed Saviour spent the Wednesday night out of doors praying in the

recesses of the hill. On the Thursday morning He went to Bethany to bid

His Mother farewell, and to obtain her consent to His Passion, as He

had before done to His Incarnation. Not that it was necessary in the

first case as it was in the last, but it was fitting and convenient to

the perfection of His filial obedience. Sister Mary of Agreda in her

revelations describes the affecting scene, how Jesus knelt to His

Mother, and begged her blessing, how she refused to bless her God, and

fell upon her knees and worshipped Him as her Creator, how He

persisted, how they both remained upon their knees, and how at last she

blessed Him, and He blessed her. Who can doubt but that He also

enriched with a special blessing His beloved Magdalen, the first and

most favored of all the daughters of Mary? He then went to Jerusalem,

whither His Mother followed Him, together with Magdalen, in order

that she might receive the Blessed Sacrament. The last Supper, the

First Mass, took place that night, our Lord's first unbloody Sacrifice,

to be followed on the morrow by that dreadful one of blood.

By a miraculous grace she assists, in spirit, at the Agony in the

Garden, sees our Lord's Heart unveiled throughout, and feels in

herself, and according to her measure, a corresponding agony. She sees

the treachery of Judas consummated, in spite of her intense prayers for

that unhappy soul. Then the curtain falls; the vision grows dim; she is

left for a while to the anguish of uncertainty. With the brave, gentle

Magdalen, she goes forth into the streets. She tries to gain admittance

both to the houses of Annas and Caiaphas, but is repulsed, as she was

at Bethlehem three-and-thirty years ago. She hears the voice of Jesus;

she hears also the blow given to her Beloved. Jesus is put in prison

for the night; and St. John comes forth, and leads our Blessed Mother

home to the house in which the last Supper had been eaten. At all the

horrors of the morning she is present. She hears the sound of the

scourging, and sees Him at the pillar, and the people around Him

sprinkled with His Blood. She hears the gentle murmurs, the almost

inaudible bleatings, of her spotless Lamb; she hears them, and

Omnipotence commands her still to live. In spirit---if not in bodily

presence---she has seen the guards of Herod mock the Everlasting. She

has

beheld the ruffians in the guard-room celebrate the cruel coronation of

the Almighty King. She has seen the eyes of the All-Seeing bandaged,

and the off-scouring of the people daring to bend the knee in derision

before Him who is one day to pronounce their endless doom. She has

looked up to the steps of Pilate's hall, and has beheld---beautiful in

His disfigurement---Him who was a worm and no man, so had they trodden

Him under foot, and mangled Him, and turned Him almost out of human

shape by their atrocities. She heard Pilate say, "Behold the Man;" and

verily there was need that some one should testify that He was man,

Who, if He had been only Man could never have survived the crushing of

the winepress which the threefold pressure---of His Father, of demons,

and of men---had inflicted upon Him. Then rose over the crowded piazza

that wild yell of blasphemous rejection by His own people, which still

rings in our ears, still echoes in history, still dwells even in that

calm heaven above, in the Mother's ear who heard it in all the savage

frightfulness of its reality. Now the Magdalen leads her home, whither

John is to come with news of the sentence when it is passed.

Quietly, almost coldly, we seem to say these things. Alas! many words

are not needed. Besides, what words could they be? To Mary's heart, to

Mary's holiness, to Mary's dolor, each minute of those hours was longer

than sheaves of centuries bound together in some one secular revolution

of the system of the world. Each separate mystery, each blow of the

scourging, each fragment of action or suffering which we can detach

from the mass, was far, far away of more value, import, size, reality,

than if at each moment a new universe, with all its immeasurable

starriness, had been called out of nothing, and peopled with beings

more beautiful than angels. It is as if the course of all nature were

quickened, and time accelerated, and all things bidden to take the

speed of thought, and flash onward to the end which God appointed. Like

the fearfulness of some gigantic machinery to a child, so to our eyes

is the vision of our Lady's holiness, cleaving its way, like some

colossal orb in terrific velocity, through the darkness, and the

blasphemy and the blood. Can her soul be the same which left Bethany

only yesterday afternoon? The Saint in his beaming glory, and the

white-faced, querulous sick man on his dying bed, are not further apart

than the Mother of yesterday and the Mother of today, apart, yet

cognizably the same. She has reached the point of the fourth dolor. She

is ready now to meet Jesus with the Cross.

St. John, at length, returns to the house with the news of the

sentence, and other information. Our dearest Mother, broken-hearted,

yet beaming as with Divine light in her tranquility, pre- pares to

leave the house with Magdalen and the Apostle. The latter, by his

knowledge of the city, will lead her to the end of a street, where she

can meet Jesus on His road to Calvary. But has she strength for such a

meeting? Not of her own; but she has as much strength to meet Him as He

has to travel by that road. For she has Himself within her, the

unconsumed species of the Blessed Sacrament. It is only with Jesus that

we can any of us meet Jesus. It was so with her. We take Him in

Viaticum, and then go to meet Him as our Judge. She took Him, in a

strange sense, in Viaticum, and went to meet Him as condemned, and on

His way to death, It was that unconsumed Blessed Sacrament, which had

carried her through the superhuman broken-heartedness of the last

twelve or fifteen hours. If that marvelous conjecture be true, as we

think it is not, that it was at the moment when the species of the

Blessed Sacrament were consumed in Himself, that our Lord cried out, My

God, My God, why hast Thou forsaken Me? we can estimate the strength

that sweet Sacrament was to her now. Everywhere the streets are

thronged with multitudes setting in one tide to Calvary. Heralds at the

corners of the streets blow their harsh trumpets, and proclaim the

sentence to the people. Mary draws her veil around her. John and the

Magdalen lean their broken hearts on hers, for they are faint and sick.

What a journey for a Mother! She hardly takes note of the streets, but

with their shadows they fling into her soul dim memories of the Pasch

twenty-one years ago, and the three bitter days that followed it. She

has taken her place, silent and still. She does not even tremble. Some

tears flow as if spontaneously from her eyes. But her cheeks are red?

Yes,---her tears were blood. The procession comes in sight; the tall

horse of the centurion shows first, and leads the way. The trumpet

sounds with a wailing clangor. The women look from the lattices above.

She sees the thieves, the crosses, every thing,---and yet only one

thing, Himself. As He draws nigh, the peace of her heart grows deeper.

It could not help it; God was approaching, and peace went before Him.

Never had maternal love sat on such a throne as that one in Mary's

heart. The anguish was unutterable. God, who knows the number of the

sands of the sea, knows it. Now Jesus has come up to her. He halts for

a moment. He lifts the one hand that is free, and clears the blood from

His eyes. Is it to see her? Rather, that she may see Him, His look of

sadness, His look of love. She approaches to embrace Him. The soldiers

thrust her rudely back. Oh, misery! and she is His Mother too! For a

moment she reeled with the push, and then again was still, her eyes

fixed on His, His eyes fixed on hers; such a link, such an embrace,

such an outpouring of love, such an overflow of sorrow! Has he less

strength than she? See! He staggers, is overweighed by the burden of

the ponderous Cross, and falls with a dull dead sound upon the street,

like the clank of falling wood. She sees it. The God of Heaven and

earth is down. Men surround Him, like butchers round a fallen beast;

they kick Him, beat Him, swear horrible oaths at Him, drag Him up again

with cruel ferocity. It is His third fall. She sees it. He is her Babe

of Bethlehem. She is helpless. She cannot get near. Omnipotence held

her heart fast. In a peace far beyond man's understanding, she followed

slowly on to Calvary, Magdalen and John beside themselves with grief,

but feeling as if grace went out from her blue mantle enabling them

also to live with broken hearts. The fourth dolor is accomplished; but

alas! we only see the outside of things.

Although this dolor seems to be but one step in the Passion, it has

nevertheless strongly-marked peculiarities of its own. The fact of its

having been selected by the Church as one of the seven sorrows of Mary

implies that it has a significancy belonging to itself. To our Blessed

Lady it was the actual advent of a long-dreaded evil. It was the

fulfillment of a vision which had been before her, sleeping and waking,

for years. It is the first of her dolors which stands clear of the

mysteries of the Infancy, and belongs to the second constellation of

her griefs, those of the Passion. There is a peculiar suffering of its

own in the coming of a misfortune which we have long been expecting.

There is such a thing as the unpreparedness of extreme preparation. We

have imagined everything beforehand. We have tried to feel the very

place where we were sure the blow would fall, and to harden beforehand.

We have placed the circumstances all round about the sorrow just in the

order and position which is our liking. We have thought over and over

again what we would think, what we would say, what we would do. We have

practised the attitude in which we intend to receive the blow. We have

left nothing unthought of, nothing unprovided for. We have made up our

minds to it. It is before us like a picture, and, though there has been

no little suffering in the anticipation, familiarity has almost taken

the sting out of our sorrow before it comes. And then it comes. Oh, the

cruel waywardness of the evil! It has not observed a single one of our

many rubrics. It has come by the wrong road, at the wrong hour, with

the

wrong weapon, ruck us in the wrong place, and borne no similarity, not

even a family resemblance, to the romance of woe for which we had

prepared ourselves. It has taken us unawares. It has disconnected us

utterly. We feel almost more wronged by this, than by the evil in

itself.

Moreover, the tension of mind and body, to which we have rung ourselves

up for endurance, renders us peculiarly susceptible of pain, and

disables us from bearing it one-half so heroically as we had resolved.

There are many men, who can meet punishment and death bravely, if it

comes at the appointed hour; but if it is deferred, the powers of the

soul, which had knit themselves up for the occasion, fall away, and

disperse, and often come soft with almost an effeminate softness. And

yet to us ordinary mortals, as the poet has justly said, "all things

are less readful than they seem;" whereas in the case of our Blessed

Lady's sorrows the realities far outstripped the most ample

expectations. They fulfilled to the uttermost the cruel pains which

were foreseen, and brought many with them likewise, as if tokens of

their presence, for which no allowance could have been made even in the

clearest prevision granted to her. The sorrow, that had been queening

it over all other sorrows for three-and-thirty years, had now met her

at last, in the streets of Jerusalem. It came to do its work for God,

and it did it, as God's instruments always do, superabundantly.

Even with our Blessed Lady there is a great difference between sight

and foresight, between reality and imagination. There is a vividness

which could never be foreseen. There is the unexpectedness of the way

in which the circumstances are grouped. There is a withdrawal of that

medium of time and unfulfillment, which before existed between the soul

and its sorrow, and which made it less harsh and galling in its

pressure. Besides which, there is a life, an announcement, an

individuality in the actual contact of the misfortune, which belongs to

each misfortune by itself, is inseparable from it, and is unshared by

any other sorrow whatsoever. It may be called the personality of the

sorrow. Alas! we all know it well enough, in our degree. Many a time it

has driven us to extremities. It is always the unbearable part of what

we have to bear. It needs not to have lived a long life to be able to

say from our own experience that there is no sameness in sorrow;

likenesses there are, but not identities. We have never had two griefs

alike. Each had its own character, and it was with its character that

it hurts us most. So it was with our dearest Mother. Her sorrows, when

they lay unborn in her mind, were hard to bear; but when they sprang to

life, and leaped from her mind, and with Simeon's sword clove her heart

asunder. They were different things, as different as waking is from

sleeping, or life from death.

There was another aggravation of her grief in this dolor in the

knowledge that the sight of her increased our Lord's sufferings. In the

preceding dolor He had been, as it were, her executioner; now she was

His. Which was the hardest to bear? Is there any loving mother who

would not rather receive pain from her son, than cause it to him? What

must this feeling have been in Mary, who transcended all maternal

excellence in the fondness and devotedness of her deep love? What must

it have been to her whose Son was God? Each outrage which had been

offered to Him, each stripe which had fallen upon His Sacred Flesh, had

been torture to her beyond compare. She had been penetrated with horror

as she thought of the cruelty and the sacrilege of which all, priests,

judges, soldiers, executioners, people, had been guilty who had taken

part in these atrocities. And behold! she herself was one of the

number. She was adding to His load.  She

was more than doubling the

weight of that heavy Cross He was carrying. The sight of her face at

the corner of that street had been worse a thousand times than the

terrible scourging at the pillar. It was her face which had thrown Him

down upon the ground in that third fall. What name can we give to a

sorrow such as this? The records of human woe furnish us with no

parallel to it which would not dishonor the subject. Some have spoken

of the meeting between Sir Thomas More and his daughter in the streets

of London. But what is the result of the allusion? Only to take the

beauty and the pathos out of that touching English scene, without

reaching the level of the sorrow we are speaking of, or reaching it

only to degrade it. It was

part of the necessity which was laid on Mary. She was to be her Son's

executioner. and, in the pain she inflicted, the cruelest of them all.

This fourth dolor was the first exercise of her dreadful office. It was

new to her; for she had never given Him pain before. But it was the

Will of God, that Will which is always sweet in its extremest

bitterness, always amiable when flesh and blood and mind are shrinking

aghast from the embrace it is throwing round them. It was that Will

which headed the procession to Calvary, that Will which was waiting on

Calvary like a luminous cloud, that Will which was a crown of thorns

round the brow of Jesus, and a Cross upon His shoulders, and a sword in

His Mother's heart, and His Mother's heart a sword in His. Had ever a

Saint such a Divine Will to conform to as Mary had? Had ever a Saint

such conformity to any Divine Will he ever encountered? She is going up

to Calvary, in brave tranquility, to help to slay the Babe of

Bethlehem. She

was more than doubling the

weight of that heavy Cross He was carrying. The sight of her face at

the corner of that street had been worse a thousand times than the

terrible scourging at the pillar. It was her face which had thrown Him

down upon the ground in that third fall. What name can we give to a

sorrow such as this? The records of human woe furnish us with no

parallel to it which would not dishonor the subject. Some have spoken

of the meeting between Sir Thomas More and his daughter in the streets

of London. But what is the result of the allusion? Only to take the

beauty and the pathos out of that touching English scene, without

reaching the level of the sorrow we are speaking of, or reaching it

only to degrade it. It was

part of the necessity which was laid on Mary. She was to be her Son's

executioner. and, in the pain she inflicted, the cruelest of them all.

This fourth dolor was the first exercise of her dreadful office. It was

new to her; for she had never given Him pain before. But it was the

Will of God, that Will which is always sweet in its extremest

bitterness, always amiable when flesh and blood and mind are shrinking

aghast from the embrace it is throwing round them. It was that Will

which headed the procession to Calvary, that Will which was waiting on

Calvary like a luminous cloud, that Will which was a crown of thorns

round the brow of Jesus, and a Cross upon His shoulders, and a sword in

His Mother's heart, and His Mother's heart a sword in His. Had ever a

Saint such a Divine Will to conform to as Mary had? Had ever a Saint

such conformity to any Divine Will he ever encountered? She is going up

to Calvary, in brave tranquility, to help to slay the Babe of

Bethlehem.

There was another grief also in this dolor, which was new to her, and

caused in her heart in an incomparable degree the acute pain which the

sight of sacrilege causes to the Saints. She saw Him in the hands of

others Who could touch Him and come near Him, while she was kept far

off. How she longed to wipe the blood from His face with her veil, to

part His tangled hair, to remove with lightest touch that cruel crown,

to lift the Cross off His shoulders and see whether her broken heart

would not give her superhuman strength to carry it for Him! Oh, there

were countless ministries in which a mother's hand was needed by that

dear Victim of our sins! And think of the plenitude of the rights she

had over Him, more than any mother over any son since the world began!

He had acknowledged them Himself. He had made her assert them openly in

the temple. But these men knew no more of the Mother of God than poor

heretics do. Moreover, they who had trampled her Son under foot would

have made but little scruple of her rights. In the times of Bethlehem

and Egypt it had been her joy to touch Him, in the performance of her

maternal office. Her love had risen so high, that it could find no vent

except in breathless reverence, and it was the touch of His Sacred Body

which hushed her soul with that thrill of reverence. Saints at the

altar have exulted with the Blessed Sacrament in their hands, till they

rose up from the predella in the light air, and swayed to and fro, like

a bough in summer, with the palpitations of their ecstasy. How many

times must we multiply that joy to reach Mary's! She had only not

grudged Joseph the embraces of her Child, because she loved him with

the holiest transports of conjugal affection, and best satisfied her

love by giving him his turn with Jesus. The novelty had never worn off.

The joy had never become thinner from use. The reverence only grew more

reverent from custom. The thought of it came back to her now, and the

waves of grief beat up against her heart as if they would have washed

it away. She had seen the filthy hands of the public executioner

grasping His neck and shoulder. She had seen the miry foot of some

sinful soldier spurning His bruised flesh. She had seen them brutally

knock the wooden Cross against His blessed head, and drive the spikes

of the thorns still farther in. St. Catherine of Genoa had to be

supported by God, lest she should die when He showed her in vision the

real malice of a venial sin. What if, with her eyes thus spiritually

couched, she had beheld the malice which can trample the Blessed

Sacrament under foot in the sewers of the street? The love of a whole

Christian land will rise with one emotion to make reparation for a

sacrilege against the Blessed Sacrament. They who have been but too

indifferent to their own sins will then afflict themselves with

fasting, and impair their own comforts by abundant alms. It is the

instinct of faith's loyalty, and of the love which lies in reality,

however appearances may be against it, at the bottom of every believing

heart. In truth, the feeling of sacrilege is like bodily pain. It is as

if we were being cruelly handled ourselves. Holy people, both religious

and seculars, have offered their lives to God in reparation of a

sacrilege, and have rejoiced when He deigned to accept the offering. To

die for the Blessed Sacrament,---that would be a sweet end, glorious

also, but more sweet than glorious, because it would so satisfy our

love! But the sacrilege that day in the streets of Jerusalem! Mary's

woe is simply unimaginable. She would have died a thousand deaths to

have made reparation. Ah, but, dearest Mother! thou must live, which to

thee is worse far than death, and thy life must be thy reparation! All

the evils which others find in death thou findest in life, and many

more beside. To thee it would be as great a joy, as all thy seven

dolors all together were a sorrow, if thou mightst not outlive three

o'clock that Friday afternoon. But there is a bar between thee and

death,---a whole omnipotence. So thou must be contented, as thou ever

art, and envy the accepted thief, and for our sakes consent to live!

There was also in this dolor a return of one of the worst sufferings

of the Flight into Egypt, only now it was in a higher degree than then.

It was terror. We always look at Mary as something very near to God,

even though infinitely far off, as the nearest creature needs must be.

It is a good habit, because it is the truth. But we must not forget

that her heart was always eminently feminine. Fancy the sea of wild

faces into which she looked in those crowded streets. Wild beasts in

the desert would have been less dreadful. Every passion was glaring out

of those ferocious eyes, rendered more horrible by their human

intelligence mingled with the inhuman fiery stare of diabolical

possession. A multitude, with the women, possibly the children, all

athirst for blood, raving after it, yelling for it as only a maddened

populace can yell. It was a very vent of hell, that voice of theirs, a

concourse of the most appalling sounds, of rage, and hate, and murder,

and blasphemy, and imprecation, and of that torturing fire in their own

hearts which those passions had fiercely lighted up. The sights and

sounds thrilled through her with agonies of fear. She was alone,

unsheltered, uncompanioned. For she was the companion to John and

Magdalen; they were not companions to her. Oh for the loneliness of the

desert, and its invisible panic, so much better to bear than this

surging multitude of possessed men! They touch her, they speak to her,

they jostle her. Visible by her blue mantle, she floats about on the

bellows of that tossing crowd, like a piece of wreck on the dark

weltering waters of a storm. And she is apart from Jesus. He is

perishing in the waves of that turbulent people. He is engulfed. She

can stretch out no hand to save Him. The Mother of tIle Maccabees

looked bravely on the fearful pomps and cruel pageants of the legal

injustice which was to make her childless, and her name justly lives,

embalmed in sacred history, and, still more, in Christian hearts. But

those faces and those cries,---earth never saw, never heard, any thing

so terrible; the demon-maddened creatures howling over their conquered

God! And to Mary it had such reality, such significance, as it could

have to no one else. Surely the suffering of fear was never more

intensely felt by any creature than it was by her on that Friday; and

the many bitter chalices she had drunk during the preceding night and

all that morning rendered her, in the ordinary course of things, less

able to bear up against this violent assault of terror. Her fear was

not so much for herself; it was for Him. Her fear, as well as her love,

was in His Heart rather than in her own. The knowledge that He was God

only deepened her terror. It was just that very thing which made the

horror of the scene unsurpassed by any other the world had ever known,

or ever could know again. The day of doom will be less terrible than

Good Friday was. Nay, it is the fearfulness of Good Friday which will

make the pomp of the last judgment so endurable, so calm, so full of

reverent sweetness. O Mother! that day will pay thee back the terror of

today; for thou wilt see thy Son in all the placid grandeur of His

human glory, with those beaming Wounds illuminating the whole circle of

the astonished earth, and thou wilt return from the valley of Josaphat

with a family of other sons, that can be counted only by millions of

millions, to be thine eternal possession in heaven, won for thee only

by the dread mysteries of this great Friday!

As we have said before, it belonged to the perfection of Mary's heart

that one ingredient of her sorrow did not absorb or neutralize another.

She felt each of them as completely as if it were simply the whole

sorrow. It possessed her with an undistracted possession. Each feature

was as if it were the entire countenance, the full face, of each dolor,

and it looked into her heart as if it, and it alone, expressed the

fulness of the mystery. Thus her terror did not kill any other of the

afflicting circumstances of this fourth dolor. As it did not perturb

her peace, so neither did it confuse her feelings or blunt her

susceptibilities. This is always one of the peculiarities of Mary's

griefs which puts them beyond the reach of parallels. Thus it was an

additional sorrow to her on the present occasion that, except St. John,

the Apostles were not following their Master to His end. The graces of

each one of them came upon her mind. She revolved the peculiarities of

the vocation of each, and all the minute tenderness and generous

forbearance on the part of Jesus to which it testified. She saw the

words of eternal wisdom pouring for those three years into their souls,

in the communication of the sublimest truths, in the pathetic kindness

of affectionate admonitions. She saw how omnipotence had placed itself

in their hands in the gift of miracles. They, like her, only for fewer

years, had fed upon the beautiful grace of Jesus. They knew the

marvelous expressions of His venerable face. The tones of His voice

were familiar to them. The touch of His hands, the look of His eye, the

very significance of His loving silence, all was known to them. They

had been drawn within the ring of its attractions. It had been to them

a new birth, a new life, an anticipated heaven. To use our Lord's

phrase, they had gone into their mother's womb again, and had been born

anew of Mary, brothers of Jesus, resemblances of Jesus. She knew that,

next to the dignity of being the Mother of God, the world could have no

vocation so high as that of being Apostles of the Word. Eternal Wisdom

had come to earth, and of all its millions He was to choose but twelve,

who should know His secrets, who should reflect Him, perpetuate Him,

hold His powers in vessels of flesh, and accomplish the work He had

begun. They were more than angels; for no angels ever bore such

messages to mankind, except the secret annunciation of Gabriel to the

Divine Mother. They were kings as none ever were before; for they were

not only to conquer the entire earth, but their thrones of judgment are

set up round His in heaven. No blood of martyrs was more precious in

their Master's sight than theirs. No doctors have ever attained to

their science. No virgins have equaled their purity, whether it were

the purity of innocence or the purity of penance. No confessors have

ever confessed as much, or confessed it more bravely. No bishops have

used the keys more liberally, more discreetly, more blamelessly than

they. No sovereign pontiff will let himself be called by Peter's name,

because none else has worn the world's tiara so gloriously or so

meekly as he. And these other Christs, gleaming with gifts, enriched

with graces, the wide world's special souls, the new paradise which God

had planted,---where were they now? Peter was in his lurking-place on

Olivet, weeping bitterly over his fall. He went to Calvary only in his

Master's heart and in Mary's. His love was not like hers. He could not

bear to see the sufferings of Him whom he loved far more than the

others loved Him. The very penitent shame of his fall made him less

able to bear so great a sorrow. The rest were hidden. They had fled

from Gethsemane, and were dispersed, the prey of grief, uncertainty,

and pity, the strength of love dubiously contending with the timidities

of despair. They have left Jesus to tread the winepress alone. When He

is risen, He will meet them with the old love, with more than the old

love, and they will hear no word of reproach from His sweet voice, and

they will see no look of reproach in the deserted Mother's eye. Only

John is there, drawn by His Saviour's love of him rather than urged by

his own love of Jesus.

The absence of the apostles was a keen aggravation of Mary's sorrow. It

was a triple wound to her. It wounded her in her love of Jesus. She

knew how deep the wound was which it made in His Sacred Heart. She saw

how, far beyond the cruel scourging and the barbarous coronation, Her

beloved was tormented by this cruel abandonment of Him by those whom He

had loved beyond the rest of men. She could go near to fathoming the

anguish which this was causing Him. Moreover, her own love of Him

underwent a cruel martyrdom in seeing Him thus deserted, and by those

whose very office should have taken them to Calvary, who should have

been witnesses of His Crucifixion as well as of His Resurrection. There

was something unexpected in it, although it was foreknown. So it always

is with ingratitude. It is a knife with so sharp an edge, that we

cannot help but start when it cuts us, however long and bitterly it has

been anticipated. We excuse much to men who think, even though it be

mistakenly, that they have been the victims of ingratitude; and thus we

acknowledge the agony of the smart. But it wounded her also in herself.

Her own love of the Apostles made her value their love of her. It was

true love, it was intense love. She knew it. Then why was John only

with her in that encounter with her Cross-laden Son, in that melancholy

pilgrimage to Calvary? A broken heart like hers could spare no love

which rightly belonged to it; and when the love of Jesus toward her was

working bitterness in her soul rather than consolation, she could the

less afford to do without such love as would simply be a joy, a rest, a

consolation. But she must not expect it. It is her place to console,

not to be consoled. Her Son came to minister, not to be ministered to.

She must participate in the same sublime office. She must empty her own

heart of consolation, and pour it all out upon the rest, keeping for

herself what is not only specially her own, but what none else are able

to receive,---the untold weight of her exceeding sorrow. It would have

been somewhat easier to have gone up to Calvary with the Apostles round

her. And yet for their sakes she was content to have John alone,

content the others should be spared what it would so overwhelm them to

behold. But their absence inflicted yet a third wound upon her heart,

in the love which she herself bore to the apostles. Their weakness was

a cruel sorrow to her love, and yet it strove with the sorrow that they

should be suffering so much as that very weakness implied. She grieved,

also, because one day it would so grieve them that they had not been

with Jesus to the last. She mourned, like. wise, because they lost so

much in after-thought by not having witnessed those appalling

mysteries. There was not a varying sorrow in the heart of anyone of

them which she did not take into her own. For they had come to her in

the place of Joseph, and she poured out on them the love she had poured

out on him. He had been with her in her three first dolors; why were

they absent from her fourth? And a gush of marvelous, unavailing love

to her departed spouse broke from the fountains of her heart as she

asked herself the question. Oh, how wonderful are the ingenuities of

suffering which love causes in the heart!

But Judas was almost a dolor by himself. We learn, from the revelations

of the saints, how she had striven in prayer for that wretched soul.

She had lavished all manner of kindness on him, as if he had been more

to her than either Peter or John. She had watched with unspeakable

horror the gradual steps by which he had been led on to the

consummation of his treachery. She had seen how sensitively the Heart

of Jesus shrank from this cruel sin, and how many scourgings would have

gone to make up the sum of pain which the traitor's single kiss had

burned in upon His blessed lips. For a while it appeared as if Judas

had been even more to her than Jesus, so had she occupied herself at

that awful season to rescue the falling Apostle, and to hinder that

tremendous sin. Moreover, none could know so truly as herself the

immensity of that sin, and the whole region of God's fair glory which

it desolated. She saw it in the Heart of Jesus. It was as if she had

been an eyewitness of the fall of Lucifer from we heights of heaven to

the inconceivable lowness of that abyss which is now his miserable and

accursed home. Terrible as was the thought that an apostle could betray

her Son, it seemed even yet more injurious to His honor that, although

Judas should have stained himself with so black a crime, he should yet

despair of mercy and doubt the infinity of his Master's love. She had

lost a soul. She had lost one of her little company. Jesus was not the

first son she was to lose. That grand apostolic soul, decked with gifts

like a whole angelic kingdom, crowned with the splendors of earth's

most beautiful vocation, canonized by the especial choice and outpoured

love of Jesus, was gone, gone down in the most frightful hopeless

wreck. Even Mary had some things to learn. This was her first lesson in

the loss of souls. If we were more like saints, we should know

something of what it meant. The Passion began by losing an Apostle's

soul, and ended by saving the soul of a poor outcast thief. Such are

the ways in which God takes His compensations.

But we have to add physical horrors now to the agonies of mind and

heart. They begin in this dolor, and are among its most marked

peculiarities. There are few persons who have ever read a book on the

Passion, from which they would not wish something to be left out. This

is not from the weakness of their faith, but from the fastidiousness of

a natural taste, which has not yet been fully refined by the

supernatural love, whose one object St. Paul so significantly divides

into two, Jesus Christ and Him Crucified. Truly penitent love would not

shrink from the contemplation of those dread realities which the Son of

God condescended to undergo for us, and into the horrors of which our

own sins drove Him. When adoration cannot swallow up sentimentality, or

invest it with a new character, it is a sign that we are wanting in a

true sense of sin as well as a true love of our Blessed Lord. It is not

well with a soul when it averts its inward eye from the Crucifixion,

and fixes it on the secret mental agony of Gethsemane, because the

three hours of the one are free from the frightful atrocities of the

three hours of the other. Reverence will not allow us to deal thus

either with our Saviour's Passion or with our Lady's dolors. Her broken

heart was surfeited with physical horrors. It was part of her

sanctification. She pressed her way through them all that day, steeling

her shrinking nature. She would not have missed one of them for all the

world.

It was a dreadful thing for a mother to walk the streets over her own

Son's blood. It was fearful to have her own feet reddened by the

Precious Blood, and the loss of Judas fresh in her afflicted soul. She

saw the crimson track which Jesus had left behind. The multitude were

mixing it up with the mud, which it tinged with a dull hue. It was on

their shoes, and upon their garments. It went up the steps of their

doorways. It splashed up the legs of the centurion's horse. No one

cared for it: No heart was touched. None suspected the heavenly

mystery,

at which Angels were gazing in silent stupor. Mary too must tread upon

it. It was sorrow almost literally trampling its own heart under foot.

She must tread on that which she was worshipping. That which colored

the street-mud, which blotched the paving-stones, which clung, half wet

and half dry, to the garments of the multitude, was hypostatically

united to the Godhead. It merited the plenitude of Divine worship.

Mary was adoring it at every step. There was not a spot tinged with

that dull red, not a garment laid by that night in a clothes-press with

those spots upon it, over which crowds of Angels were not stooping, and

would remain to guard it till the moment of the Resurrection. Surely

this is unutterable woe, over which the heart should spread itself in

silence only.

In this dolor also we must notice particularly, what has been observed

before, the union in Mary of horror of sin with intense anguish because

of the misfortune of sinners. She saw some who were handling our Lord

or shouting after Him, in completest ignorance, without so much as a

suspicion of the dreadful work in which they were engaged. They were

obdurate sinners, hardened by ungodliness, who sinned almost as they

would breathe the air or move their limbs, All ignorance of God was

pain to her, now especially that souls were beginning to belong to her.

But the ignorance of a seared conscience was a grief too deep for

tears, a phenomenon she would have longed should not exist upon the

face of God's weary earth. How dark it was! how hopeless! Even now

Eternal Truth was looking it in the face, and, alas! only blinding it!

Then there were others whose malice was more intelligent, who were

consciously satisfying some evil passion, hatred of purity perhaps, or

the spite of untruthfulness against truth, or the envy which meekness

always excites when it is very heavenly and heroic, or political

vengeance, or the long-treasured anger against one who had reproved

them, or the mere love of cruelty, and the excitement of human fury

which the smell of blood causes in men as in beasts. All this she saw.

She trembled at the horror of the vision. She was heart-stricken by the

thought of Him, the gentle blameless One, against whom all this was

concentrated. She was pierced also by the sharpest anguish from the

love of the very sinners themselves. She would not have called fire

down from heaven, as James and John were fain to do upon the Samaritan

village. She craved not for judgments. She would have deprecated with

all the might of her holiest impetrations the advent of a destroying

Angel. She must have those souls. She has lost Judas. She claims

consolation. Into those dark minds the light of faith shall be poured.

Over those blood-stained souls more Blood, more of the same Blood,

shall flow, but it shall be in gentlest fertilizing absolutions. On

those blaspheming tongues the Blessed Sacrament shall lie. She will

travail in pain with them till they are born again in Christ. So she

too goes up to Calvary with a work to do. Look well at her heart! She

will accomplish it. There are few things the sanctity of human sorrow

cannot do. God seems to treat it as a power almost coequal with

Himself. But here in our Blessed Mother, what sanctity! what sorrow!

Then, as if the very contrast had called it forth, there rose up before

her the most vivid vision of the beautiful Infancy. It was true that

from the very first her life had been dismantled by an enduring sorrow.

Nevertheless how peaceful and how sweet seemed the old days at

Nazareth, and even the cool evening airs on the brink of the distant

Nile, compared with the violence and noise and bloodshed of this

fearful Passion! Then, when her arms were round Him, she had pressed at

once her sorrow and her love to her bosom. She had held quiet

colloquies with Him. He belonged only to her, for Joseph ,vas most

truly a second self. Now she had given Him away, not in thought only,

not in the tranquility of a heroic intention, but in reality. He was

not only in the hands of others, but He was taken from hers. Anyone

could come near Him, except herself. She alone had lost her rights.

Every action of the Holy Childhood came before her, and found its

bitter contrast in the scene that was then enacting in the streets of

Jerusalem. She thought how she had washed Him, clothed Him, given Him

food, nursed Him to sleep, and knelt down and worshipped Him when He

was asleep, though she knew well He could see her even then. Every one

of those things found their opposites with dreadful accuracy in the Way

of the Cross. Earth; and blood, and shameful spittings defiled His face

and hands and feet. His hair, from which handfuls had been pulled, was

clotted, entangled, and deranged. His tunic clung painfully to the

half-congealed blood of His wounds. Alas for those baths of His

childhood and the reverent ministries of His loving Mother! We shall

come to them again in the sixth dolor, and then how changed the

circumstances! They have once torn His garments from the wounds, and

made them bleed afresh. They will do so again at the top of Calvary. It

was not thus she had undressed Him in the quiet sanctuary of Nazareth.

He had had no food but the sins of men, and a very feast of ignominy,

since the evening before. He was worn with want of sleep, but will

never sleep again now. She thought of tears which ran silently down His

cheeks in the days of His Childhood. Why should they not have redeemed

the world, and washed all sin away, seeing their worth was infinite?

Oh, how busy memory was in that hour with its comparisons and its

contrasts! and there was not one which did not heighten the misery of

the present. Could she be a mere mortal to go up to Calvary with a will

nestling so tranquilly alongside of the will of God, with a heart

broken to pieces, yet out of whose rents not one breath of her

peacefulness had been allowed to escape? Yes! she was mortal, but she

was also the Mother of the Eternal, and loving hearts alone know how

those two things contradict each other, and yet are true together.

Such was the fourth dolor. Let us now examine the dispositions in which

she endured it. First of all, there was the unretracted generosity of

the oblation she had made. Amid the multitude of thoughts, which in all

her sorrows passed through her mind, her will lay still. So completely

was she clothed in holiness from head to foot, that it never so much as

occurred to her to think that the load might be lightened, or the pangs

mitigated, or the circumstances be more tolerably disposed. When we

have committed ourselves to God, we have committed ourselves to more

than we know. John had not reckoned on the long years of weary waiting

in the exile of life, when he said he could drink his Master's cup. So

is it with all of us. We find that what God really exacts from us is

more than we seemed to be promising. The more He loves us, the more

exacting does He become. He treats us as if we were more royal-hearted

than we are, and by His grace He makes us so. Our Lady knew more of the

length and breadth and depth of her oblation than anyone, else had ever

done. It was this which made her lifelong sorrow so much more real and

intense than the mere foresight of a prophet or a Saint. Nevertheless,

even she probably, though she knew all, did not realize all. Probably

she could not compress into a vision, no matter how piercingly clear,

that slow pressure which the lapse of time lays upon a sorrowing heart.

Thus in its totality, in the disposition of its circumstances, in the

combination of its peculiarities, in their united pressure, and in the

long years of their endurance, as well as the actual impressions of the

senses, her sorrow was not more than she meant to promise, because she

meant to promise all, she meant herself to be a holocaust, a whole

burnt-offering to the Lord, but it might be more than she realized at

the moment that she promised. She was a creature. We need to be

reminded of that, because the magnificence of her sanctity so often

makes us almost forget it. St. Denys said he should hardly have known

her to be a mere creature, if he had not been told.

Now, this consideration renders still more wonderful the unretracted

generosity of her offering. If she was not taken by surprise in any of

her sufferings, she felt new things coming upon her. She was sinking

into depths deeper than had been revealed to her. The actual horror of

the present shut out some of the light, which had lighted her down the

abysses, when she had explored them in mental anguish only. Yet she

went on in tranquility. God was welcome to it all, welcome to more if

His omnipotence should see fit to anneal her heart to bear a stronger

heat. She had cried out once. It was an awful moment. It was in the

great temple of the nation, before the doctors of her people. But her

Creator Himself had wrung it from her, partly because He yearned to

load her with another world of graces, and partly because He loved to

hear it, seeing that it worshipped Him so wonderfully. Job sanctified

himself by the patience of his complaining. Low as we are, how imitable

the virtue of Job seems by the side of Mary's generous endurance! Even

great saints have begun to sink, when called, like Peter, to walk upon

the waters. As to ourselves, even in our little sorrows, how hard it is

to keep to God, and not to turn aside, and lie down, and rest our heads

on the lap of creatures, and bid them whisper consolations in our ear,

as a respite to us for a while from the oppression of God's vicinity!

What does our perseverance look like at best but a running fight

between grace and time, the one to win which chances, for it seems a

chance, to have struck the last blow when the death-bell sounds? But

are not those saints the most indulgent to others who have been the

most austere to themselves? Is it not ever the unmortified who are the

critical? Do not they always stoop lowest who have. to stoop from the

greatest heights? So will Mary be all the better mother for us in the

dust in which we creep, frightened, shrinking, and despairing, because

of the sublimities of that generosity of hers, which is always above

the clouds, always with the eternal sunshine on its brow.

We must observe also the firm hand which our Blessed Lady kept upon her

grief. Amid the jostling of the crowd, she seemed as if she were

impassible. There was not a gesture or a movement which betrayed the

slightest interior emotion. When they repulsed her from Jesus, and

barbarously interposed between the embrace of the Mother and the Son,

there was no impatience in her manner, no resentment on her

countenance, no expostulation on her lips. She possessed her soul

perfectly. The movements of the Blessed in the visible presence of God

in heaven could not be more regulated than were hers. St. Ambrose has

dwelt at length upon this excellence of hers. Yet we must not conceive

of our Blessed Mother, as of a coldly graceful statue, never descending

from her pedestal because she was heavenly marble, and not flesh and

blood. Statues have not broken hearts. This calm imperturbability of

her demeanor arose from the sublimity of her holiness, which itself

arose in no slight degree from the intensity of her sorrow. The

excesses of her suffering were commuted into excesses of tranquility,

which looked superhuman only because what is completely and perfectly

and exclusively human is seen nowhere but in her. This is the picture

we must always draw of our Blessed Lady. She is woman, true woman, but

not mere woman. We shall sadly degrade her in our own minds, if for the

sake of facility or effect we venture to exaggerate the feminine

element beyond what we find it in the Gospels. It is easy to distort

the image of Jesus. When men speak of His compassion to sinners, they

often throw a sentimentality over the narrative, which is far removed

from the calm gentleness of Scripture. They think they bring Him nearer

to us by making Him as like ourselves as doctrine will allow them, and

all the while they are excavating an impassable gulf between Him and

us, and casting Him leagues and leagues away from us. Unfortunately

this lowering process is yet more easy with Mary, for she has no

Divinity to save her in the long run. A merely feminine Mary is not the

Mary of the Bible. Neither again is she a simple shadow of our Lord, or

her mysteries a repetition of His. If we endeavor to establish any

parity, even a proportionate one, between her and our Lord, we only

meddle with Him without really elevating her. She had not two Natures;

her Person was not Divine; she was not the Redeemer of the world; she

was not clothed in our sins; the anger of the Father never directly

rested upon her; her innocence was not His sinlessness; her Compassion

was not His Passion; her Assumption was not His Ascension. She stands

by herself. She has her own meaning, her appropriate significancy. She

is a distinct vastness in God's creation. She is without a parallel.

Jesus is not a parallel to her, nor she to Him. She fills up the room

of a huge world in the universe of God, but the room she fills is not

the room of the Sacred Humanity of Jesus, nor even like to it. She is

Mary. She is the Mother of God. She is herself. Near to God yet every

whit a creature, sinless yet wholly human, human in person, and not

Divine,---in nature human only, and not divine also. They who represent

her as a pale shadowy counterpart of our Blessed Lord, changing the sex

and lowering the realities, miss the real grandeur of Mary as much as

they miss the peculiar magnificence of the Incarnation. Thus it comes

to pass that if, in order to paint her sorrows in more striking colors,

we exaggerate what is feminine about her, we obtain the same result

with those who insist in finding in her all manner of unequal

equalities with her Son, namely, an unworthy view of her as well as an

untrue one. She is more like the invisible God than like the Incarnate

God. She is more accurately to be paralleled with what is purely Divine

than with what is human and Divine together. She is a creature clothed

with the eternal sun, as St. John saw her in the Apocalypse, the most

perfect created transcript of the Creator. As the Hypostatic Union

links Creator and creature literally together, so Mary, the divinely

perfect, pure creature, is the neck which joins on the whole body of

creatures to their Divine Incarnate Head. She has her own place in the

system of creation, and her own meaning. She is like no one. No one is

like her. What she is most like is the Incomprehensible Creator. Thus,

of the three elements into which the idea of Mary resolves itself in

our minds, the feminine element, the element of the Hypostatic Union,

and the Divine element, it is this last which seems to control the

rest, while all three are so inextricably commingled that we can detach

none of them without injury to truth.

We must also not omit to mention here the union of Mary's sorrows with

our Lord's. We have spoken of it before; but a new and very significant

feature in this disposition of hers comes to view in the fourth dolor.

There is such a gracious unity vouchsafed to us between our Blessed

Lord and ourselves,---between the Redeemer and the Redeemed,---that we

may, not in mere imagination or as an intellectual process of faith,

unite our sufferings to His, and so make them meritorious of eternal

life. It is chiefly the more excellent attainment of this union which

distinguishes the Saints from ourselves. Theologians have said that the

great difference between the service of the Blessed in heaven and the

service of the elect on earth is, that on earth the soul unites itself

to God by the exercise of a variety of virtues, whereas in heaven Jesus

Christ is the one virtue of the Blessed, the link which joins them to

the Father. Some saints have been allowed, in a certain measure and by

a very peculiar gift, to anticipate on earth this heavenly

particularity, and to be clothed in an unusual way with the very spirit

of Jesus. Cardinal de Berulle was even said to have the gift of

communicating this spirit in a subordinate degree to the souls which he

directed. Of course no Saint, nor all the Saints put together, ever

possessed the spirit of Jesus so nearly to identity as His Blessed

Mother. Hence in all her dolors she suffered in the most unspeakable

union with Him. But in this one the invisible realities of the

spiritual life seem to come up to the surface, and pass into outward

facts, into the actualities of external sensible life. Her sorrows and

His became almost indistinguishably one,---in fact as well as feeling,

in reality as well as faith, in endurance as well as love. It was His

suffering which made her suffer. The way in which He suffered she

suffered. His dispositions were her dispositions. Nay, it was rather in

Him than in herself that she suffered. His very sufferings were her

very sufferings. It was only as His that they were hers. And her

sufferings made Him suffer; they were His worst sufferings. He suffered

in her, as she in Him. They were exchanging hearts, or living in each

other's hearts, all the while in that journey to Calvary. She seemed to

have put off her personality, and to have become to Jesus a second

multiplied capacity of suffering. Never was union more complete; never

were the inner mystical life of the soul and the outward present life

of tangible facts so identical before. We have no terms to express the

union, which would not at the same time confound the Mother in the Son,

and so be undoctrinal, unfaithful, and untrue.

In speaking of the peculiarities of this dolor, we have already seen