OF THE PASSION:

+++++++ Saint John the Baptist +++++++

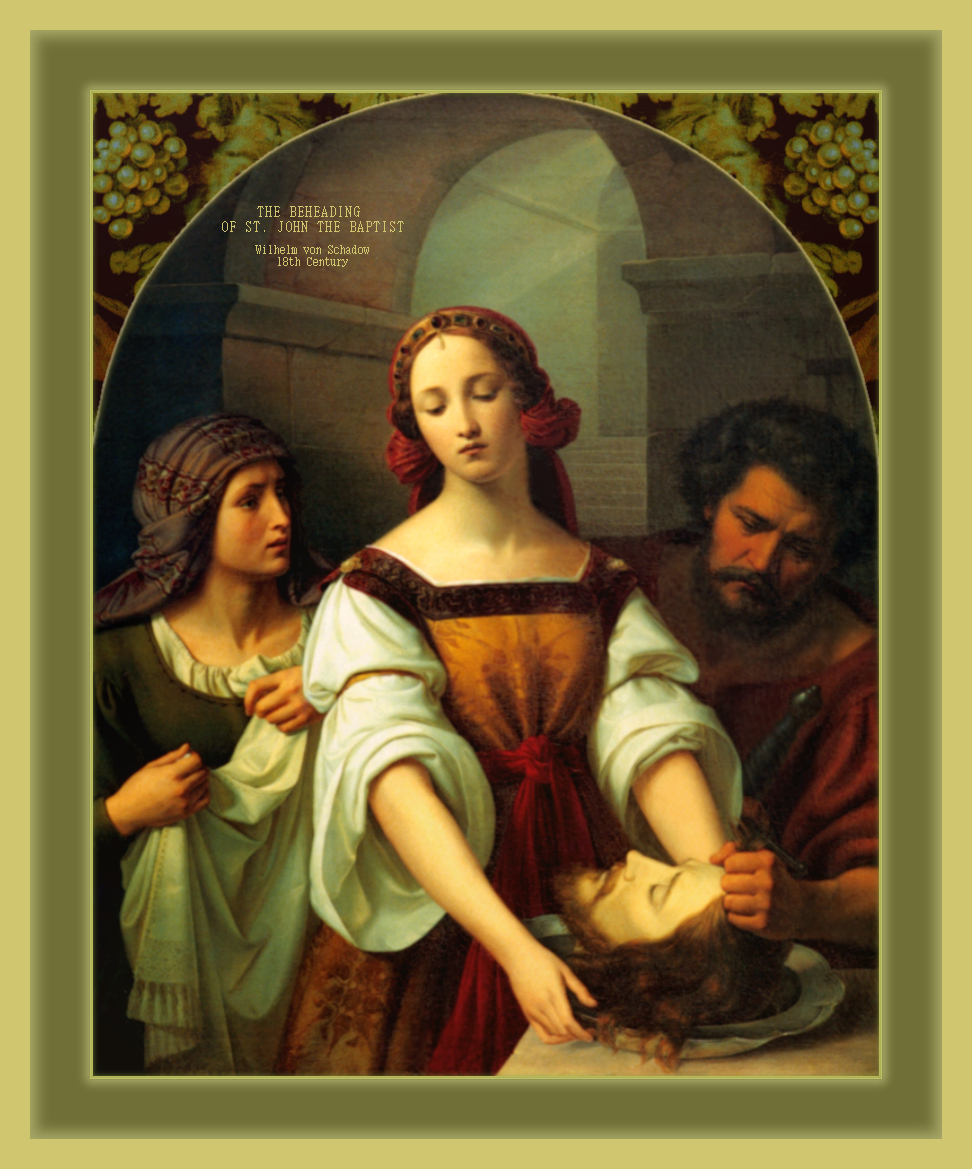

6. The Death of John the Baptist The Public Life of Our Lord, Jesus Christ, Vol. 1 by Bishop Alban Goodier, SJ; NOW there comes upon the scene another character, whose name provokes only contempt; except for this, that with such an ancestry, and with such an upbringing, contempt is softened into pity. Herod Antipas, the son of the Great Herod who had rebuilt the Temple in Jerusalem, and had massacred the Innocents in Bethlehem, and had died of a foul disease while his hands were still steeped in blood, had been reigning tetrarch of Galilee for these thirty years and more. The Romans had put him there when, on his father's death, they had found it convenient for themselves to partition the country. Their soldiers kept him there, at once a watch upon him and a guard to overawe the people. Their officials ruled the district for him, including Galilee and all Perrea, with such Jewish assistance as was needed for their purpose. As for himself, so long as he gave no trouble, he could do very much as he liked. And he did as he liked. The reaction from the cruel treatment of his boyhood had been great. Bred of a stock of mingled Eastern and Western blood, born of a merciless father, brought up in constant and imminent fear, with the blood of his brethren and relations continually flowing about him, an atheist of atheists with not a noble ideal in his soul, he had made up his mind, once he was secure, to compensate at any cost for the misery of his early life. What a time during these last years he had had! Convention scattered to the winds; an Eastern monarch was beyond convention and criticism, and the blood of the Eastern monarch was in him. Safe from the prying eyes of his people he had fortified himself in his palace of Machrerus, aloft in the mountains overlooking the Dead Sea. There he had lived, with pleasuse only as his object, growing more callous and cruel as he indulged himself the more, gathering about him such courtiers as would encourage him in his revels, petty magnates, local rulers, rich men who affected Magdala, women who were ready to sell themselves for a share in his orgies. For thirty years it had gone on, from bad to worse; for just those thirty years during which Jesus, his subject, was hidden away at Nazareth. Then had appeared that interfering John. In the midst of his revels, for a single crime committed, one man had dared to denounce him to his face. He had put him in prison; for security he had taken him far away from his favourite Jordan. He had locked him up in the dungeon of his own castle; and though all the world had resented it, yet not a man subject to him had dared to raise a hand in protest. To the Romans, moreover, John was of no concern. The Jews with their religion were a dangerous thing to handle; so long as Herod did not go beyond their law he could do with his own zealots what he liked. Indeed the more he embroiled himself with them the more his Roman overlords would like it. With John in prison Herod knew he had nothing to fear. But unfortunately the trouble had not ended there. Herod had visited John in prison. He was always curious about religious revivalists, always on the lookout for a fresh excitement and distraction, and such men as John were a diversion. Moreover, as is common with his kind, he was superstitious, and John had for him an irresistible fascination. But these visits had strangely affected him. John in prison began to gain a hold on Herod. His anger had waned, and had gradually changed to awe, his awe to fear, fear to respect, and Herod had of late become less gay, less reckless, more thoughtful and moody. This had affected his courtiers. Their master of the revels was turning gloomy, morose, capricious, ill-tempered, unmanageable, uninterested; if they were not careful, now that age and unceasmg self-indulgence were beginning to tell upon him, he might develop like his father and turn on them. It was all because of John; somehow John must be got out of the way. The women in particular would not be thwarted by such vermin. At Machrerus John lingered in his prison, surrounded by more enemies thirsting for his blood than his keeper Herod. Among these women was one who had long made up her mind that he would be her victim. Herodias had been the wife of Philip, the brother of Herod, not the then ruling tetrarch of Iturea and the country to the north, but an elder brother of that name. But he had been much too meek and quiet for Herodias, and his court was all too mild. Through Philip she had come to know his brother Herod; he and his way of living were much more suited to her taste. In spite of Philip she had angled for him; after all Philip had not cared. She had captured him; she had gone away with him to Machrerus, and there she had reigned as its queen. Then had come this John from the Jordan with his unwarranted interference. She had had this serpent scotched; she had prevailed on Herod to close his mouth and clap him in prison, no matter what the despicable rabble might say. But she had not been able to do more. None of her further hints had been taken; none of her caresses had prevailed anything. On the contrary; of late Herod had grown annoyed at the mention of the name of John, and she had found it prudent to desist. Still there was war declared between that woman in the palace and that man in prison, war to the death, war for the soul of Herod, war for her own throne; if she failed she was cast out from her world of revelry, she and her daughter with her. But she would not fail. She would bide her time; like a tigress she would watch her opportunity, and, when the occasion came, like a tigress she would spring. At last the occasion did come. John had now been in prison some four months. The Pasch was drawing near; within a week or a fortnight pilgrims would be coming down the Jordan valley through Perrea to go up to Jerusalem. They would miss John at the ford; they would certainly talk about him. That he was known to be alive over at Machrerus might stir trouble; and trouble at paschal time was liable to be hard to control. Herodias was more on the alert than ever. But before the Pasch there was held every year at Machrerus a much more solemn festival. About that time was Herod's birthday; more important still, it was the anniversary of Herod's coming to the crown, and Hcrod always celebrated this event with more than customary revelry. This year, both Herod and Herodias took care that the ceremony and feasting should be more than usually brilliant. To him the year had not been a very great success. Both his marriage and this business with John had, he suspected, put him out of favour, even with his boon companions. He must live the matter down; he must brazen it out; he must be more lavish than usual. Such people easily forgave a brave fellow, who affected not to care, who defied God and man, and whose wealth and luxuries were at their service. As for Herodias, she had her own plans. Herod must be roused from this moroseness that was growing upon him; he was beginning to show signs of a conscience, and that must at once be killed. He was given to excess. When roused his passions would make him dare anything; when in a bragging mood there was nothing he might not say. Who knew what might not happen? To the fullest of her powers she would humour him, flatter him, capture him, even if she had to use her own daughter as a bait. So it came about that in that year the celebration of Herod's birthday was an unusually grand affair. Invitations had gone out, with special inducements and attractions, though experience had long since taught many that they would have a good time. Caravans had come in, round the north of the Dead Sea, bringing petty chiefs from all about, and heads of the army, and magnates from Galilee and Perrea, Jews and Gentiles, Romans and Asiatics,---round the loaded table of Herod they sank their differences; as for religion, though at home they said it was the breath of their nostrils, for the time being it was left outside. Religion of any kind did not go well with Herod's banquets; it was best forgotten for the moment. When the revelry was over, and some of them would need to make their way from Machrerus to Jerusalem for the Pasch, they could pick it up again along the road. They settled down to table, stretched out on their couches; what happened then does not concern us. The more solid eating was done; the guests were feeling satisfied with themselves and with their host; Herod was on this account in better humour. Then came other amusements. There was music, stirring every nerve; dancing, stirring every passion; of that, too, we need not say more. Only at a special moment, well-timed, a single dancing girl flashed in, and from the moment that her delicate foot touched the floor she had conquered every eye that glared at her. For glare at her they did; in their sodden state they would have glared at every dancing girl; had they been sober, a creature such as this would have caught them. She danced and danced, and the jewels upon her danced with her. Like a snake she curved her lithe body, and thc spell entered into every soul that was there. Her dark eyes of fire fascinated, her laughing lips invited, her whole figure drew. She addressed herself to all; at times, in the ecstasy of movement, she seemed to address herself to none; but all the while, with the subtlety of infinite guile, her meshes were all thrown in one direction. Herod! Cost what it might that man must be conquered. Her mother had impressed it on her, before she entered that room; she herself knew she was playing for a great stake. And Herod responded. He knew her who she was, though many at the moment did not know. He was proud of her; he was won by her; she was a credit to his family and his court. He would reward her for this, though for the moment his heated brain could not tell him how. What would please the girl? She should choose for herself. Whatever she might ask, what did it matter? The dancing ceased. With all the simplicity of a delicate maiden the damsel made her curtsey and smiled. The guests applauded, everyone applauded. In spite of their much experience these men had not seen dancing like this before; for once they were aroused. Who was the girl? Whence did she come? And the word went round that she was the daughter of Herodias, the former wife of Philip, the present wife of their host, Herod. They turned their congratulations on him. This was indeed a crowning feat to such a sumptuous banquet; it did Herod honour. How proud he must be of such an addition to his household! And so on, and so on. In the world's subtle way they let him know that if he was in need of their forgiveness for his act of indiscretion, he was forgiven. And Herod's heart was turned. He succumbed to their flattery. Filled with red wine, he cared not now what he said or did. The girl had danced his misery away; she had danced him back into the favour of his flatterers. She should be rewarded; in a right royal way he would reward her. When the applause had ceased, and the talk had sunk again into a murmur, at last he spoke. Loud and boasting and full of low passion he cried out: 'Ask of me what thou wilt And I will give it thee.' The girl stood still. She knew well the part she had to play. She affected to be frightened; she hesitated; in her heart what she sought was some assurance that her wily uncle would abide by his word. He saw her hesitation, the questioning look in her eyes; he was sober enough for that. He saw the guests gazing at him, gazing from him to her, astonished at his boldness, with their eyes almost challenging him to stand by what he said. He would not go back; nay, he would go further; these men should see what a daredevil he was. He leaned forward on the table towards the girl. He raised his arm asa pledge of his fidelity. He uttered a binding oath; then added, huskily, aggressively: 'Whatsoever thou shalt ask I will give thee Though it be the half of my kingdom.' It was enough; having sworn such an oath before so many witnesses Herod could never draw back. But she must not delay; he might yet repent; the guests would soon depart, and she would lose the influence of their presence. She made her bow and hurried from the room to her mother. To her she told her story. These two knew one another, worthy daughter of such a mother; they knew that their faters wereinevitably interlaced. They must plot together; in good and in evil they must take evil share. 'What shall I ask?' said the daughter, more than suspecting what the answer would be. The mother did not hesitate. How she had waited for this moment! We can see the hard face set, intent upon its prey; the burning, hating eyes already glittering in their anticapted triumph; the beauty of that Asiatic coutenance frozen into something terrible, as without a moment's pause she hissed out: 'The head of John the Baptist.' There was no waiting. The maiden tripped back into the baqueting hall; merrily, gracefully, as if it were all only a child's prank and whim. This time, as she came in, there was dead silence in the room; even the half-drunken men knew well what she migt ask might be momentous. Then in the silence the damsel grew stern. The child rose suddenly to a woman. Her face took on her mother's hard look, her eyes were fixed fast on Herod. With them she seemed to hold him to his promise, in some way to threaten him, even while with a graceful curtsey she said the words: 'I will That forthwith thou give me Here in a dish The head of John the Baptist.' Such a request, on such an occasion, from such a creature! Even those hardened worldlings were appalled. They had heard in their time brazen women say many hideous things, and had laughed at them; angry women shriek out things which men would never dare to say, and had enjoyed it as a show. Romans among them had seen women, vestal virgins, in their amphitheatres, turn down their thumbs in heartless contempt, and so seal a gladiator's doom. But this was something wholly different. That slight dancing girl, asking for the life of that man! Asking for his bleeding head as her plaything! That man's life depending on the whim of such a creature! Even they could scarcely hold their indignation, their disgust. Yet had Herod sworn to please her; he had sworn it in the prescnce of this crew. He could not draw back; his coward heart could not face that humiliation. She was daring him to do what he had promised; he must not be beaten. His face lost its colour; he hung his head as if he wished to think. The silence grew more tense; every eye was upon him, above all the cruel eyes of that unflinching dancing girl. There was no escape; he must keep his promise. A negro guard of giant stature stood beside the curtain at the door. Herod gave him a sign. He had heard the girl's request; let him see that it was granted to her. Let him go at once and bring back to him here on a dish the head of the prisoner, John the Baptist. The guard saluted like an automaton, turned on his heel, lifted the curtain and disappeared; it was now too late for Herod to recall his words. In that room there was now amazing silence. Now and then one or another tried to break the spell but it would not be broken; they lifted the load that weighed on them, but it fell back again. These men, one and all, had seen men die before; cruelty was a second nature to them. More than one had done a slave to death for a trifling annoyance; a woman's death when she became inconvenient, was an ordinary thing to some amongst them; some had sanctioned death to satisfy a jealous wife. But this death, of this man, under these conditions, to please the whim of a laughing, smirking dancing girl,---the horror of it would not leave them. They looked at her where she stood on the floor in front of them, in all her finery and jewels, smiling as simply as if she were but toying with a trifle, yet with a set look in her eyes and a tightening of her lips which declared she would not be baulked of her prey. They admired, they hated, they were fascinated, they were repelled. They would not have missed this show for anything, yet they despised themselves for being there. Presently there was heard a shuffling on the steps outside. The grip on those men grew more intense; their hearts stood still; like frozen corpses they lay around the table; in the midst, like a statue, stood the girl. The silken curtain at the entrance was drawn carefully aside; it must not be stained. From underneath, in all his richest armour and accoutrement, stepped the giant negro, swarthy, thick-muscled, carrying a silver dish. On the dish was something; was it what they longed, yet feared to see? There was long dark hair hanging wet over the edge; there was darkened ooze dripping down it. Presently that upon the dish appeared, blue-black and livid, eyes half-open but lustreless, nose pinched to terror, cheeks sunk and hollow, lips apart as if they were prepared to speak, blood trickling out from either end. It was a human head; it was the head; those who had known him in life recognized the head of John the Baptist. The negro stood at the entrance with his trophy. He would present it to Herod; put it on the table before him with his wine and fruit; trophies were becoming ornaments to dining tables. But Herod would have none of it; even the guests shrank from that. Hastily he pointed to the girl who still stood before him, triumph now getting the better of her, hatred becoming beyond control, eagerness to seize her prey passing all restraint. With due ceremony the negro turned to her; solemnly he bowed to her, as to one whom his master chose to honour. He held out the dish. He hoped it would not be too heavy for this delicate maiden. He hoped she would not tremble at the sight of blood and let it fall. A fall of such a thing upon the floor would be ill-omened. But he need not fear. She did not tremble. Eagerly she seized the dish resting it on both her delicate arms; to her breast she pressed it for security. She now forgot her manners; Herod and his party could for the moment be ignored. Glaring at her treasure she turned and rushed out of the room; the servants shrank aside as she passed, lest blood should drip upon them. 'And he beheaded him in prison And his head was brought in a dish And it was given to the damsel And she brought it And gave it to her mother.' There we may leave the two gloating over their victory; when woman hates she ceases to be human. Let us close the story as the Evangelist closes it: 'Which his disciples hearing Came and took his body And buried it in a tomb And came and told Jesus.' |

E-MAIL

E-MAIL

HOME-------------PASSION---------------SAINTS

www.catholictradition.org/Passion/john-baptist3b.htm