SELECTIONS BY PAULY FONGEMIE

Unearthing the Time-Bombs

It was shown in the previous chapter that too much blame should not be attached to the Council Fathers for failing to detect the time-bombs which had been inserted in the Con- situation on the Sacred Liturgy (which will be referred to from now on as CSL). In his authoritative book, La Nouvelle Messe, Louis Salleron remarks that far from seeing it as a means of initiating a revolution, the ordinary layman would have considered the CSL as the crowning achievement of the work of liturgical renewal which had been in progress for a hundred years. [La Nouvelle Messe, Paris, 1970, p. 17] Let there be no mistake, there was great need and great scope for liturgical renewal within the Roman rite, but a renewal within the correct sense of the term, using and developing the existing liturgy to its fullest potential. As was remarked in Chapter II, where, as in the case of Mesnil St. Loup, this was done, the life of the Mystical Body became manifest; Catholicism was seen as it could be but rarely was. [Emphasis in bold added here and infra.]

It could be argued that the study of the CSL which is to be made here lacks balance as it says little about the admirable doctrinal teaching and pastoral counsel which the Constitution contains, while stressing a few alleged deficiencies. The fact is that the liturgical revolution which has emerged from the Constitution has been initiated precisely on the basis of the very few clauses discussed in this chapter. Those who gained control of the Consilium which implemented the CSL used these clauses in precisely the manner they had intended to use them when, as members of the conciliar Liturgical Commission, they had inserted them into the CSL. The Constitution itself became a dead letter almost from the moment that it was passed with such euphoria by the Council Fathers. It could have been used to initiate the type of true renewal initiated by Pere Emmanuel in Mesnil St. Loup, a renewal faithful to the authentic liturgical principles endorsed by the popes and expounded in documents ranging from Tra le sollicitudini of St. Pius X ( 1903) to the De musica sacra et sacra liturgia of Pope Pius XII ( 1958). [The Liturgy (Papal Teaching series, St. Paul Editions, 1962] But discussing what might have been is the most fruitless of occupations - it is what actually happened that matters. "Are these Fathers planning a revolution?" demanded a horrified Cardinal Ottaviani during the debate on the liturgy. [Letters from Vatican City, X. Rynne, New York, 1963, p. 116] Indeed they were, or at least the periti as whose mouthpieces they acted were. The extent to which this was the case has been made clear in earlier chapters, Chapter V in particular; the full extent of episcopal subservience to the diktat of the "experts" was made clear by Archbishop Lefebvre in a lecture which he gave in Vienna in September 1975. He explains that the French episcopal conference "held meetings during which they were given the exact texts of the speeches they had to make. 'You, Bishop So-and-So, you will speak on such a subject, a certain theologian will write the text for you, and all you have to do is read it." [Approaches, February 1976, Econe Supplement, p. 21]

A revolution had indeed been planned - and it was to be initiated by the time-bombs concealed in the CSL. It is with these liberal time-bombs that this chapter is primarily concerned, not with the orthodox padding used to conceal them.

No Catholic can be too familiar with Mediator Dei. It is, perhaps, the most perfect exposition of the nature of the liturgy which has ever been written. In this encyclical Pope Pius XII defines the liturgy as follows: "The sacred liturgy is the public worship which our Redeemer, the Head of the Church, offers to His heavenly Father and which the community of Christ's faithful pays to its Founder, and through Him to the Eternal Father; briefly, it is the whole public worship of the Mystical Body of Jesus Christ, Head and members." This definition requires us to bear in mind, when discussing the CSL and the reforms purporting to emanate from it, that:

1. The liturgy is primarily an act of worship offered to the eternal Father.

2. It is an action of Christ, actio Christi, something Christ does.

3. The members of the Mystical Body associate themselves with their Head in offering this worship.

These principles, of course, apply to the entire Divine Office and not simply to the Mass. Pope Pius explains that the essence of the Mass is found in the fact that it is an action of Christ, the extension of His priesthood "through the ages, since the sacred liturgy is nothing else but the exercise of that priestly office."

Our word liturgy is derived from the Greek leitourgos, which originally designated a man who performed a public service. In the fifth century B.C., a leitourgos in Athens fitted out a warship at his own expense, trained the crew and commanded it in battle. In Hebrews 8, 1-6, Christ is referred to as the Leitourgos of holy things. The liturgy is His public religious work for His people, His ministry, His redeeming activity. It is above all His sacrifice, the sacrifice of the Cross, the same sacrifice that He offered on Calvary still offered by Him through the ministry of His priests. He is the principal offerer of the sacrifice of the Mass and to offer the Mass nothing is necessary but a priest, the bread, and the wine. There is no necessity whatsoever for a congregation; when defining the essence, the nature of the Mass, the presence of the faithful need not be taken into account; while it is obviously desirable it is not necessary. When the faithful are present they are able to join themselves in mind and heart with what Christ does in His liturgy. We offer Him and we offer ourselves with Him. (The fact that the faithful offer the sacrifice with and through the priest is stressed in Mediator Dei.) Needless to say, even when a priest offers Mass with only a server it is still a public act of worship made by the whole Church for:

Every time the priest re-enacts what the Divine Redeemer did at the Last Supper, the sacrifice is really accomplished; and this sacrifice always and everywhere, necessarily and of its very nature, has a public and social character. For he who offers it acts in the name both of Christ and of the faithful, of whom the Divine Redeemer is the Head, and he offers it to God for the Holy Catholic Church, and for the living and the dead. [Mediator Dei, para. 86, CT translation on line]

According to Robert Kaiser, the battle over the CSL was won by the liberals on 7 December 1962 when the preface and first chapter were approved with only eleven dissenting votes.

To the Council's progressives, euphoric over other battles fought and won, this was a sweet message. True, they would have to vote on other chapters But they would be mere formalities. "Within the preface and first chapter," a member of the Liturgical Commission told me, "are the seeds of all the other reforms." It was true also that the Pope would have to ratify the action. But no one thought he would attempt to veto what the Council had spent so long achieving. [Inside The Council, R. Kaiser, London, 1963, p. 122]

He did not! One of the first points made in the preface is that the Council intends to "nurture whatever can contribute to the unity of all who believe in Christ: and to strengthen those aspects of the Church which can help to summon all of mankind into her embrace." Those who drafted the Constitution clearly envisage the liturgy as a means of promoting ecumenism. It follows from this that the traditional Roman Mass which emphasized precisely those aspects of our faith most unacceptable to Protestants must be considered as hampering ecumenism.

However, the CSL gives the impression that there is no danger of any drastic change in any of the existing rites of Mass. among which the Roman rite was clearly paramount. as: "this most sacred Council declares that holy Mother Church holds all lawfully acknowledged rites to be of equal authority and dignity: that she wishes to preserve them in the future and to foster them in every way." (Author's emphasis in Italics.) These reassuring words are qualified by the additional desire of the Council that: "where necessary the rites be carefully and thoroughly revised in the light of sound tradition, and that they be given new vigor to meet the circumstances and needs of modern times." (Art. 4.) How it is possible to preserve these rites while revising them to meet certain unspecified circumstances and needs of modern times is not explained. Nor is it explained how such a revision could be carried out in the light of sound tradition as it had been the sound (and invariable) tradition of the Roman rite never to undertake any drastic revision of its rites, a tradition of well over 1,000 years standing which had been breached only during the Protestant Reformation, when every heretical sect devised new rites to correspond with its new teachings.

There had, of course, been liturgical development within the Roman rite, as in all rites, but it had been by the scarcely perceptible process described in Chapter IX of Cranmer's Godly Order. It is important to note that the predominant characteristic of this development was the addition of new prayers and gestures which manifested ever more clearly the mystery enshrined in the Mass. As is made clear in Cranmer's Godly Order, the Protestant Reformers removed prayers which made Catholic doctrine specific, under the guise of an alleged return to primitive simplicity. Pope Pius XII specifically condemned "certain attempts to reintroduce ancient rites and liturgies" on the grounds that they were primitive. He designated it as

an attempt to revive the "archaeologist" to which the pseudo-synod of Pistoia gave rise; it seeks also to reintroduce the pernicious errors which led to that synod and resulted from it and which the Church, in her capacity of watchful guardian of "the deposit of faith" entrusted to her by her Divine Founder, has rightly condemned. It is a wicked movement, that tends to paralyze the sanctifying and salutary action by which the liturgy leads the children of adoption on the path to their heavenly Father. [Mediator Dei, para. 64]

The liturgical principles of Pistoia have, of course, been imposed throughout the Roman rite as part of the conciliar reforms, even though not specifically ordered by the Council - but, as this chapter will make very clear, the CSL provided the door through which they entered. It is worth pointing out that the "circumstances and needs of modern times", which article 4 of the CSL claims that the liturgy must be adjusted to meet, have occurred with great regularity throughout history. It is within the nature of time to become more modern with the passing of each second, and if the Church had adapted the liturgy to keep up with the constant succession of modern times and new circumstances there would never have been any liturgical stability at all. If this need does exist it must always have existed, and it seems hard to believe that the Holy Ghost had not been guiding the Church until He revealed it to the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council. The corpus of papal teaching on the liturgy since 1740 is readily available. [The Liturgy (Papal Teaching series, St. Paul Editions, 1962] Papal teaching on the need to adapt the liturgy to keep pace with modern times is conspicuous only by its absence - and this is hardly surprising when this alleged "need" is examined in a dispassionate and rational manner. When do times become modern? How long do they remain modern? What are the criteria by which modernity is assessed? When does one modernity cease and another modernity come into being?

The complete fallacy of this adaptation to modernity thesis was certainly not lost upon some of the Council Fathers. Bishop (now Cardinal) Dino Staffa pointed out the theological consequences of an "adapted liturgy" on 24 October 1962. He told 2,337 assembled Fathers:

It is said that the Sacred Liturgy must be adapted to times and circumstances which have changed. Here also we ought to look at the consequences. For customs, even the very face of society, change fast and will change even faster. What seems agreeable to the wishes of the multitude today will appear incongruous after thirty or fifty years. We must conclude then that after thirty or fifty years all, or almost all of the liturgy would have to be changed again. This seems to be logical according to the premises, this seems logical to me, but hardly fitting (decorum) for the Sacred Liturgy, hardly useful for the dignity of the Church, hardly safe for the integrity and unity of the faith, hardly favoring the unity of discipline. While the world therefore tends to unity more and more every day, especially in its manner of working or living, are we of the Latin Church going to break the admirable liturgical unity and divide into nations, regions. even provinces? Inside The Council, R. Kaiser, London, 1963, p. 130]

The answer, of course, is that this is precisely what the Latin Church was going to do and did; with the consequences for the integrity and unity both of faith and discipline which Bishop Staffa had foreseen.

Articles 5 to 13 which deal with the nature of the liturgy contain much admirable doctrinal teaching but also some which seems disturbingly lacking in precision. Christ's substantial presence in the Blessed Sacrament is referred to as if it is simply the highest (maximal) expression of His presence in the liturgy, a presence which is listed in a variety of manners such as the reading of Holy Scripture or the fact that two or three are gathered together in His name. He is present "especially under the Eucharistic species" (Praesens ... maxime sub speciebus eucharisticis: Article 7). One fact which is made very clear in Cranmer's Godly Order is that all the Protestant Reformers agreed that Christ was present in the Eucharist, what they rejected was the dogma of His substantial presence. If there is one word which was and is anathema to Protestants it is the word "transubstantiation." Protestants will profess belief in Christ's "real presence," in His "eucharistic presence," in His "sacramental presence" - Lutherans even accept His "consubstantial presence"- but what they will not accept, what is anathema to them, is the one word "transubstantiation." It is, therefore, astonishing to find that this word does not appear anywhere within the text of the CSL. This is a scarcely credible break with the tradition of the Catholic and Roman Church in insisting on total and absolute precision when treating of the sacrament which is her greatest treasure for it is nothing less than God incarnate Himself, Whose Mystical Body the Church is. The contrast between the traditional precision of the Church and the CSL can he made clear with just one example. Compared with the CSL the following would seem to be an extremely, perhaps an exceptionally, comprehensive definition of Christ's Eucharistic presence. "Christ is after the consecration, truly, really and substantially present under the appearances of bread and wine and the whole substance of bread and wine has then ceased to exist, only the appearances remaining." Readers will be surprised to learn that this definition was condemned as "pernicious, derogatory to the expounding of Catholic truth (perniciosa, derogans expositioni veritatis catholicae)." This was, in fact, the definition put forward by the Jansenist Synod of Pistoia and was condemned by Pope Pius VI specifically for its calculated omission of the term "transubstantiation" which had been used by Trent in defining the manner of Christ's Eucharistic presence and in the solemn definition of profession of faith subscribed to by the Fathers of that Council (quam velut articulum fidei Tridentinum Concilium definivit (D. 877, 884), et quae in solemni fidei professione continetur). The failure to utilize the word "transubstantiation" was condemned by Pope Pius VI "inasmuch as, through an unauthorized and suspicious omission of this kind, mention is omitted of an article relating to the faith, and also of a word consecrated by the Church to safeguard the profession of that article against heresy, and because it tends to result in its being forgotten as if it were merely a scholastic question." [Denz. 1529]

While discussing this particular point it is impossible not to note what could be described as the truly supernatural correspondence between what Pope Pius VI wrote in 1794 and what Pope Paul VI wrote in his encyclical Mysterium Fidei in 1965. Mention has been made in earlier chapters of the antipathy this encyclical aroused among both Protestants and liberal Catholics who did not hesitate to stigmatize it as incompatible with the "spirit" of Vatican II! Pope Paul condemns opinions relating to "Masses celebrated privately, to the dogma of transubstantiation and to eucharistic worship. They seem to think that although a doctrine has been defined once by the Church it is open to anyone to ignore it or to give it an interpretation that whittles away the natural meaning of the words or the accepted sense of the concepts." [Mysterium Fidei, para. 10] The Church teaches us, insists Pope Paul, that our blessed Lord "becomes present in the sacrament precisely by a change of the bread's whole substance into His Body and the wine's whole substance into His Blood. This is clearly a remarkable and singular change and the Catholic Church gives it the suitable and accurate name of transubstantiation." [Ibid., para 46] Mention has already been made in this book of Pope John's claim in his opening speech to the Council that: "The substance of the ancient doctrine of the deposit of faith is one thing, and the Way in which it is presented is another." Pope Paul states in Mysterium Fidei:

This rule of speech has been introduced by the Church in the long run of centuries with the protection of the Holy Spirit. She has confirmed it with the authority of the Councils. It has become more than once the token and standard of orthodox faith. It must be observed religiously. No one may presume to alter it at will, or on the pretext of new knowledge. For it would be intolerable if the dogmatic formulas, which ecumenical Councils have employed in dealing with the mysteries of the most holy Trinity, were to be accused of being badly attuned to the men of our day, and other formulas were rashly introduced to replace them. It is equally intolerable that anyone on his own initiative should want to modify the formulas with which the Council of Trent has proposed the eucharistic mystery for belief. These formulas, and others too, which the Church employs in proposing dogmas of faith, express concepts which are not tied to any specified cultural system. They are not restricted to any fixed development of the sciences nor to one or other of the theological schools. [Ibid., para 24]

How it is possible to reconcile such statements not only with those of Pope Paul, the Pope of the Council, but Pope Paul who has been inflexible in imposing the spirit, the "orientations" of the Council, it is difficult to say. There is little that can be added to what was written in Chapter XIII, let it suffice here to say that Peter has spoken through Paul.

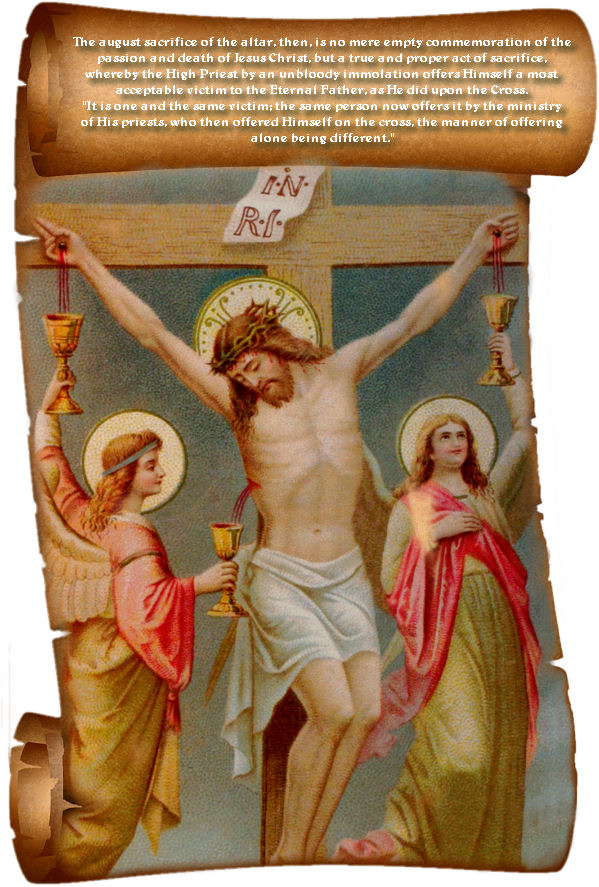

Notwithstanding the deplorable absence of the term "transubstantiation" from the CSL, Articles 5 to 13 do contain much orthodox teaching, teaching which must have gone a long way towards prompting conservative Fathers to vote for the Constitution and diverting attention from the time-bombs in the text. The victory and triumph of Christ's death are again made present whenever the Mass is offered (para 6). The Mass is offered by Christ "the same one now offering through the ministry of priests, who formerly offered Himself on the cross" (Art. 7). "Rightly then is the liturgy considered as an exercise of the priestly office of Jesus Christ" (Art. 6). It is "the summit toward which all the activity of the Church is directed; at the same time it is the fountain from which all her power flows" (para 10).

In Article 11 there appears one of the key themes of the CSL. Pastors of souls are urged to ensure that "the faithful take part knowingly, actively, and fruitfully." Similar admonitions are included in Mediator Dei but in this encyclical and in the CSL the Latin word which has been translated as "active" is actuosus. There is a Latin word activus which is defined in Lewis and Short's Latin Dictionary as active, practical, opposed to contemplativus. The same dictionary explains actuosus as implying activity with the accessory idea of zeal, subjective impulse. It is not easy to provide an exact English equivalent of actuosus, the word involves a sincere, intense perhaps, interior participation in the Mass - and it is always to this interior participation to which prime consideration must be given. The role of external gestures is to manifest this interior participation without which they are totally without value. These signs should not only manifest but aid the interior participation which they symbolize, no gesture approved by the Church is without meaning and value - the striking of the breast during the Confiteor, making the sign of the Cross on the forehead, lips, and heart at the Gospel, genuflecting at the Incarnatus est during the Creed and the Verbum caro factum est of the Last Gospel, kneeling for certain parts of the Mass, the Canon in particular, bowing in adoration at the elevations, joining in the chants and appropriate responses - all these are appropriate external manifestations of the internal participation which the faithful should rightly be taught to make knowingly and fruitfully. But Pope Pius XII points out that the importance of this external participation should not be exaggerated and that every Catholic has the right to assist at Mass in the manner which he finds most helpful.

People differ so widely in character, temperament and intelligence that it is impossible for them all to be affected in the same way by the same communal prayers, hymns, and sacred actions. Besides, spiritual needs and dispositions are not the same in all, nor do these remain unchanged in the same individual at different times. Are we therefore to say - as we should have to say if such an opinion were true - that all these Christians are unable to take part in the Eucharistic Sacrifice or to enjoy its benefits? Of course they can, and in ways which many find easier: for example, by devoutly meditating on the mysteries of Jesus Christ, or by performing other religious exercises and saying other prayers which, though different in form from the liturgical prayers, are by their nature in keeping with them. [Mediator Dei, para 108]

As Pope Pius explains at great length in Mediator Dei, what really matters is that the faithful should unite themselves with the priest at the altar in offering Christ and should offer themselves together with the Divine Victim, with and through the great High Priest Himself.

There is a clear change of emphasis between Mediator Dei and the CSL which states (Art. 14) that "in the restoration of the sacred liturgy, this full and active participation by all the people is the aim to be considered before all else, for it is the primary and indispensable source from which the faithful are to derive the true Christian spirit." (Author's emphasis.) As a footnote in the Abbott translation remarks with perfect accuracy: "This theme of awareness and active participation by the faithful is another basic theme of the Constitution." [Abbott, p. 143] Now interpreted in the sense given to the word actuosus in this chapter, this "basic theme" can be placed within the context of the liturgical movement given such impetus by St. Pius X and his successors. But as actuosus has been invariably translated by the word active, which is interpreted in its literal sense, the necessity of making, as paragraph 14 directs, full and active congregational participation the prime consideration in "the restoration and promotion of the sacred liturgy," has resulted in the congregation rather than the Divine victim becoming the focus of attention. On a practical level it is the coming together of the community which matters, not the reason they come together; and this is in harmony with the most obvious tendency within the post-conciliar Church - to replace the cult of God with the cult of man. This is, of course, in perfect conformity with the direction being taken by the present ecumenical movement, a point which was examined in Chapter VIII.

Once the logic of making the active participation of the congregation the prime consideration of the liturgy is accepted, there can be no restraint upon the self-appointed experts intent upon its total de-sacralization. It is important to stress here that at no time during the reform have the wishes of the laity ever been taken into consideration. Just as in the Soviet Union the Communist Party "interprets the will of the people" so the "experts" interpret the wishes of the laity. When, as early as March 1964, members of the laity in England were making it quite clear that they neither liked nor wanted the liturgical changes being imposed upon them, one of England's most fervent apostles of liturgical innovation, Dom Gregory Murray, put them in their place in the clearest possible terms in a letter to The Tablet: "The plea that the laity as a body do not want liturgical change, whether in rite or in language, is, I submit, quite beside the point." He insists that it is "not a question of what people want; it is a question of what is good for them." [The Tablet, March 14, 1964, p. 303]

Hence the demand that the full and active participation of the congregation "be considered before all else" is a time bomb of virtually unlimited destructive power placed in the hands of those invested with the power to implement in practice the details of a reform which the Council authorized but did not spell out in detail. Thus, although the Council says that "other things being equal" Gregorian chant should be given pride of place in liturgical services (Art. 116), the "experts" can and did argue that this was most certainly not a case of other things being equal as the use of Gregorian chant impeded the active participation of the people. The music of the people, popular music, pop music, is, say the "experts," clearly what is most pleasing to them and most likely to promote their active participation which, in obedience to the Council, must be considered above all else. This has led to the abomination of the "Folk Mass" which certainly has no more in common with genuine folk-music than it does with plainchant. It also illustrates the ignorance of, and contempt for, the ordinary faithful manifested by these self-styled "experts."

Because the housewife or the manual worker listens to pop music on a transistor to relieve the monotony of the day's routine, it does not follow that they are incapable of appreciating anything better, or that they wish to hear the same sort of music in Church on Sunday. The same is equally true of young people; if the liturgy is reduced to the level of imitating what was being heard in the discotheques last year then the young will soon see little point in being present. Dietrich von Hildebrand has correctly defined the issue at stake as

whether we better meet Christ in the Mass by soaring up to Him, or by dragging Him down into our own pedestrian, workaday world. The innovators would replace holy intimacy with Christ by an unbecoming familiarity. The new liturgy actually threatens to frustrate the confrontation with Christ, for it discourages reverence in the face of mystery, precludes awe, and all but extinguishes a sense of sacredness. What really matters, surely, is not whether the faithful feel at home at Mass, but whether they are drawn out of their ordinary lives into the world of Christ - whether their attitude is the response of ultimate reverence: whether they are imbued with the reality of Christ. [Triumph, October 1966]

It is worth noting that Professor von Hildebrand issued this warning against the clear direction which the liturgical reform was taking in 1966, a direction in which it was being steered by "experts" claiming that they knew the style of celebration which was necessary to ensure that the congregation could participate actively and this, they could point out, was what the Council had decreed must "be considered before all else."

The next time-bomb is located in Article 21. It states that "the liturgy is made up of unchangeable elements divinely instituted and elements subject to change." This is perfectly correct - but it does not follow that because certain elements could be changed they ought to be changed. The entire liturgical tradition of the Roman rite contradicts such an assertion. "What we may call the 'archaisms' of the Missal," writes Dom Cabrol, "father" of the liturgical movement, "are the expressions of the faith of our fathers which it is our duty to watch over and hand on to posterity." [Cranmer's Godly Order, M. T. Davies, Devon, 1976, p. 83] Similarly in their defense of the Bull Apostolicae Curae, the Catholic Bishops of the Province of Westminster insisted that in adhering rigidly to the rite handed down to us we can always feel secure ... And this sound method is that which the Catholic Church has always followed ... to subtract prayers and ceremonies in previous use, and even to remodel the existing rites in the most drastic manner, is a proposition for which we know of no historical foundation, and which appears to us absolutely incredible. Hence Cranmer in taking this unprecedented course acted, in our opinion, with the most inconceivable rashness. [Ibid., p. 61]

But the CSL takes a different view, so startling and unprecedented a break with tradition that it seems scarcely credible the Fathers voted for it. The CSL states that elements which are subject to change "not only may but ought to be changed with the passing of time if features have by chance crept in which are less harmonious with the intimate nature of the liturgy, or if existing elements have grown less functional." These norms are so vague that the scope for interpreting them is virtually limitless, and it must be kept in mind continually that those who drafted them would be the men with the power to interpret them. No indication is given of which aspects of the liturgy are referred to here; no indication is given of the meaning of "less functional" (how much less is "less"?), or whether "functional" refers to the original function or a new one which may have been acquired. All the Mass vestments could be abolished on the basis of this norm - they no longer fulfill their original function of standard dress in the early years of the Church. On the other hand they have now acquired an important symbolic function and could also be said to add to the dignity of the celebration.

Article 21 refers, of course, to the liturgy in general but specific reference is made to the Mass in Article 50.

The rite of the Mass is to be revised in such a way that the intrinsic nature and purpose of its several parts, as also the connection between them, can be more clearly manifested, and that devout and active participation by the faithful can be more easily accomplished.

For this purpose the rites are to be simplified, while due care is taken to preserve their substance. Elements which, with the passage of time, came to be duplicated, or were added with but little advantage, are now to be discarded. Where opportunity allows or necessity demands, other elements which have suffered injury through the accidents of history are now to be restored to the earlier norm of the holy Fathers. Those who have read Cranmer's Godly Order will be struck immediately by the fact that Cranmer himself could have written this passage as the basis for his own reform! There is not one point here which he did not claim to be implementing. Pawley has already been cited in Chapter IX as praising the manner in which the liturgical reform following Vatican II not only corresponds with but has even surpassed the reform of Cranmer. It will be shown in the third book of this series what a very close correspondence there is between the prayers which Cranmer felt had been added to the Mass "with little advantage" (almost invariably prayers which made Catholic teaching explicit) and those which the members of the Consilium, which implemented the norms of Vatican II (with the help of Protestant advisers), also decreed had been added "with little advantage" and must "be discarded."

Article 21, together with such Articles as 1, 23, 50, 62, and 88, provides a mandate for the supreme goal of the liturgical revolutionaries - that of a permanently evolving liturgy. [A detailed study of this point is available in the Approaches supplement, Report From Occupied Rome] In September 1968 the bulletin of the Archbishopric of Paris, Presence et Dialogue, called for a permanent revolution in these words: "It is no longer possible, in a period when the world is developing so rapidly, to consider rites as definitively fixed once and for all. They need to be regularly revised." This is precisely the consequence which Bishop Staffa had warned would be inevitable, in the speech cited earlier in this chapter. Once the logic of Article 21 is accepted there can be no alternative to a permanently evolving liturgy. It was explained in Chapter VI how the Council periti established the journal Concilium which can be considered as their official mouthpiece. Writing in this journal in 1969, Fr. H. Hennings, Dean of Studies of the Liturgical Institute of Trier, writes:

When the Constitution states that one of the aims is "to adapt more suitably to the needs of our own times those institutions which are subject to change" (Art I; see also Arts. 21, 23, 62, 88) it clearly expresses the dynamic elements in the Council's idea of the liturgy. The "needs of our time" can always be better understood and therefore demand other solutions; the needs of the next generation can again lead to other consequences for the way worship should operate and be fitted into the overall activity of the Church. The basic principle of the Constitution may be summarized as applying the principle of a Church which is constantly in a state of reform (ecclesia semper reformanda) to the liturgy which is always in the state of reform (Liturgia semper reformanda). [The author, Mr. Davies, does not sAy so here, but the so-called principle, ecclesia semper reformanda, is actually a principle of the second Reformation and not a part of Catholic practice. Many a modernist likes to use this principle a as if one is bound to accept any change proffered by experts. - The web Master] And the implied renewal must not be understood as limited to eliminating possible abuses but as that always necessary renewal of a Church endowed with all the potential that must lead to fullness and pluriformity. It is a mistake to think of liturgical reform as an occasional spring clean that settles liturgical problems for another period of rest. [Concilium, February 1969, p. 64]

This could hardly be more explicit. It is clear that Cardinal Heenan was not speaking entirely in jest when he remarked:

There is a certain poetic justice in the humiliation of the Catholic Church at the hands of liturgical anarchists. Catholics used to laugh at Anglicans for being"high"or"low"... The old boast that the Mass is everywhere the same and that Catholics are happy whichever priest celebrates is no longer true. When on 7 December, 1962 the bishops voted overwhelmingly (1,922 against 11) in favor of the first chapter of the Constitution on the Liturgy they did not realize that they were initiating a process which after the Council would cause confusion and bitterness throughout the Church. [A Crown of Thorns, Cardinal J. Heenan, London, 1974, p. 367]

This concept of a permanently evolving liturgy is of crucial importance. St. Pius V's ideal of liturgical uniformity within the Roman rite was considered as a reasonable ideal by Fr. Adrian Fortescue, England's greatest liturgist. [Cranmer's Godly Order, M. T. Davies, Devon, 1976, p. 73] But this ideal has now been cast aside to be replaced by one of "pluriformity" in which the liturgy must be kept in a state of constant flux. ...

We have seen, during these past years, the abolition of those sublime gestures of devotion and piety such as signs of the cross, kissing of the altar which symbolizes Christ, genuflections, etc., gestures which the secretary of the congregation responsible for liturgical reform, Fr. Annibale Bugnini, has dared publicly to describe as "anachronisms" and "wearisome externals." Instead, a puerile form of rite has been imposed, noisy, uncouth and extremely boring. And hypocritically, no notice has been taken of the disturbance and disgust of the faithful . . Resounding success has been claimed for it because a proportion of the faithful has been trained to repeat mechanically a succession of phrases which through repetition have already lost their effect. We have witnessed with horror the introduction into our churches of hideous parodies of the sacred texts, of tunes and instruments more suited to the tavern. And the instigator and persistent advocate of these so-called "youth masses" is none other than Fr. Annibale Bugnini. It is here recalled that he insisted on continuing the "yea, yea Masses" in Rome, and got his way despite the protest of Rome's Vicar General, Cardinal Dell'Acqua. During the pontificate of John XXIII, Bugnini had been expelled from the Lateran University where he was a teacher of liturgy precisely because he held such ideas - only to become, later, secretary of the congregation dealing with liturgical reform.

The background to Archbishop Bugnini's dismissal has already been examined in Chapter XII. It would be impossible to place too much stress upon the fact that Archbishop Bugnini was the moving spirit behind the entire liturgical reform - a point which, with surprising lack of discretion, L'Osservatore Romano emphasized when it attempted to camouflage the reason for his abrupt dismissal by lavishing praise upon him. Mgr. Bugnini was, the Vatican journal explained, the co-ordinator and animator who had directed the work of the commissions. [L'Osservatore Romano, July 20, 1975] It also needs to be stressed that the liturgical reform was not concerned solely with the Mass but extended to all the Sacraments, not hesitating to interfere with their very matter and form in some instances. The wholesale and drastic nature of this reform constitutes a breach with tradition unprecedented in the history of the Church - and the fact

that the co-ordinator and animator who directed it was a Freemason must rightly give every faithful Catholic cause for alarm. While this book (and this series) is concerned principally with the Mass, the next volume will devote some space to changes made in the rites of some of the other sacraments. The modifications made in the rite of Ordination are, if anything, even more serious than those made in the Mass. Pope Paul himself had to intervene and personally correct the very serious deficiencies in the new Order of Baptism for Infants which had been promulgated with his approval in 1969. [Notitiae, No. 85, July-August, 1973, pp. 268-272] This provides another demonstration of the fact that papally approved texts are not, and should not be, exempt from criticism - particularly when they involve changes in traditional rites. Had the Pope not been made aware of the serious disquiet aroused by the new Order of Baptism for infants he might not have re-examined it and made the important revisions which he promulgated in 1973.

Finally, some comfort at least can be taken from the fact that Archbishop Bugnini's Masonic associations were discovered in time to prevent him fully implementing the fourth and final stage of his revolution. He had divided this revolution into four stages - firstly, the transition from Latin to the vernacular; secondly, the reform of the liturgical books; thirdly, the translation of the liturgical books; and fourthly, as he explained in his journal Notitiae, "the adaptation or 'incarnation' of the Roman form of the liturgy into the usages and mentalities of each individual Church, is now beginning and will be pursued with ever increasing care and preparation." [Op cit., note 30]

Archbishop Bugnini made this boast in 1974, and in some countries, India in particular, the fourth stage was already well advanced when he was dismissed in 1975. Only time will reveal whether it has been possible to contain or even reverse this process of adaptation - and the extent to which the desire to reverse it exists in the Vatican.

HOME

---------------------- TRADITION